Although India began opening up its capital account in the mid-1990s, the approach towards financial liberalisation has been cautious. Tracing changes in the de-facto openness of the country’s capital account over time, Aggarwal et al. contend that greater financial integration with global markets along with monetary policy autonomy to successfully pursue an inflation target, reduces the policy space available to the RBI to stabilise currency fluctuations.

In a keynote address in November 2020, the Governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Shaktikanta Das, said, “Capital account convertibility would be a continued process, rather than an event, even as the country had progressed quite considerably in its quest towards full convertibility and internationalisation of its financial markets”.

This brings to the fore an important question: Has India’s capital account become more open over the past few years?1

India gradually began opening up its capital account from the mid-1990s. This was part of a broader agenda of liberalisation and deregulation reforms initiated after the balance of payments crisis of 1991. However, the approach adopted towards financial liberalisation has been a rather cautious one. In fact, India is the only country – other than China – that still has in place a complex and elaborate legal and regulatory framework of capital controls, and an extensive array of restrictions on capital account transactions2.

While authorities have been relaxing the legal restrictions governing foreign investment flows, from time-to-time new restrictions are imposed as well3. Typically, this is done to satisfy myriad objectives such as limiting exchange rate fluctuations, dealing with volatility in financial markets, etc. This ad hoc, discretionary approach towards capital account liberalisation makes it difficult to understand how integrated India’s financial markets are with the rest of the world.

In a recent study (Aggarwal et al. 2021), we analyse the changes over time in India’s capital account openness using a price-based measure of deviations from covered interest parity (CIP). CIP is a pure arbitrage condition, and deviations from the condition are computed as the spread between the onshore (that is, domestic) interest rate and the offshore-market (that is, foreign) implied interest rate, expressed in domestic currency.

The essence is that large gaps between the onshore rate and offshore rate cannot be sustained for long. If such gaps do exist, arbitrage opportunities will arise. In the absence of capital controls and no transactions costs, these arbitrage opportunities will be exploited, and the CIP deviation will come down to zero. On the other hand, large and persistent arbitrage opportunities for a long period of time imply that the agents are unable to exploit the arbitrage opportunities primarily owing to the presence of binding capital controls. In that case there might be significant deviations from the CIP. Thus, the smaller the value of CIP deviation the greater the capital account openness of the country in question.

We use data from Thomson Reuters spanning more than 20 years, from August 1999 to January 2021, to estimate CIP deviation in India and examine the evolution of India’s financial liberalisation process. We also consider de-jure changes in India’s capital controls in terms of ‘easing’ and ‘tightening’ events during our sample period, and relate these changes to the patterns of CIP deviations that we uncover in our analysis4.

Patterns of India’s financial integration

The CIP condition relies on a market-determined ‘forward rate’5, and the corresponding ‘spot rate’ for the same currency pair. It also assumes comparability across instruments in terms of maturity, liquidity, and credit risk. We use the most liquid, one-month, offshore non-deliverable forward (NDF) rate for the US dollar-Indian rupee currency pair and the onshore spot rate6. We use the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) and the Mumbai Interbank Offer Rate (MIBOR), both of one-month maturity, as the foreign and domestic interest rate, respectively. Using these variables, we analyse the changes in the NDF implied rate and the onshore interest rate over time7.

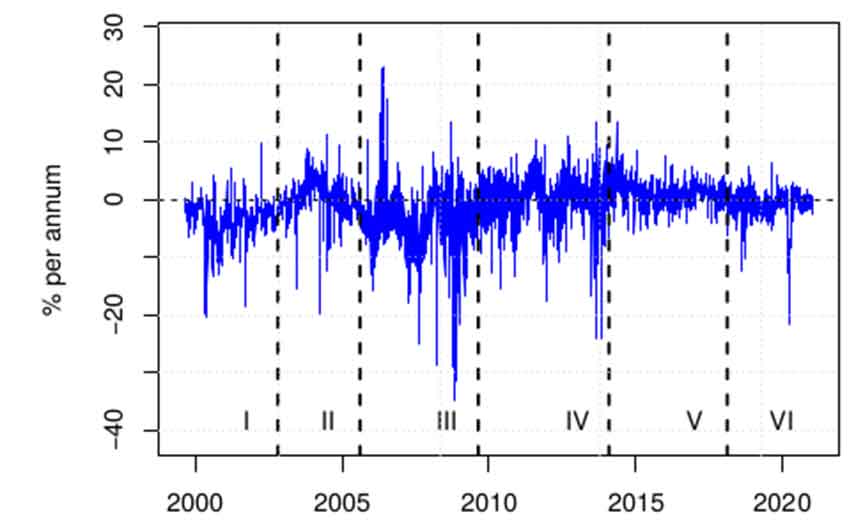

During the time period of our study, India witnessed several changes in its policy on capital account liberalisation, with some measures directed towards relaxation of capital controls while others intended to further tighten the restrictions. To better understand the resultant financial liberalisation process, we estimate structural breaks in the CIP deviations. We then connect the sub-periods with documented changes in capital controls and underlying macroeconomic conditions. We find six regimes of financial integration during the study period. These six sub-periods along with the corresponding dates and CIP deviations are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Daily CIP deviations, August 1999-January 2021

We find that the first sub-period lasted from August 1999 to October 2002. While existing literature (see, for example, Pandey et al. 2020, 2021) has documented several easing events in capital controls during this time period, the magnitude of CIP deviations (373 basis points)8 indicates that India’s capital account was reasonably closed9. The liberalisation process initiated in the early- to mid-1990s was presumably not yet substantial, or would have become effective with a long lag, given that this entailed a big change in the status quo.

The second sub-period ranges from October 2002 to August 2005. The average CIP deviation during this period was much lower at 25 basis points, compared to the first sub-period indicating greater financial integration. The favourable macroeconomic conditions during this period, along with the steady process of capital account liberalisation since the mid-1990s that encouraged significant capital inflows, potentially explain the reduction in the size of the CIP deviation.

In the next sub-period, which spans from August 2005 to August 2009, the CIP deviations witnessed huge spikes. This is consistent with the patterns seen in the CIP all over the world during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) period. India continued the relaxation of capital controls on foreign investment flows. In fact, 2008 witnessed a high number of ‘easing events’, that is, relaxation of restrictions on foreign portfolio investments (Pandey et al. 2020). At the same time several new restrictions were imposed on external commercial borrowings of domestic companies (Pandey et al. 2021). In particular, 2007 witnessed a significant amount of tightening of capital controls in response to a surge in capital inflows. The average CIP deviation during this period was 379 basis points making it the period with the widest deviation implying relatively closed capital account, similar to the 1999-2002 period.

The fourth sub-period runs from August 2009 to February 2014 capturing the post-GFC years. The average CIP deviation during this period was only 2 basis points, significantly lower than all the previous periods. This implies that India’s capital account opened up quite a bit, and participants could exploit cross-border arbitrage opportunities that arise due to higher CIP deviations. The years 2012 and 2013 witnessed a fair number of relaxations of capital controls, on the inflows of foreign portfolio investments (Pandey et al. 2020).

The fifth sub-period extends from February 2014 to February 2018. During this period, the average value of CIP deviations reveals a larger gap of 112 basis points. Most of it could presumably be attributed to the lagged impact of the capital control actions undertaken in 2013 to prevent foreign investment outflows, in the context of the Taper Tantrum episode of May 201310 and the consequent depreciation of the rupee.

In the final sub-period of our sample which runs from February 2018 to January 2021, we find that average CIP deviation was down to -0.94, implying continued reduction of barriers on foreign investments11. The volatility of the CIP deviations was among the lowest during this period.

Overall, our analysis reveals large variations in the CIP deviations during the sample period, though we find that the magnitude of these deviations has come down over time. If we look at the average CIP deviations before and after the GFC (2008-09), we find that in the pre-GFC period the average deviation was -2.58 and this goes down to -0.03 in the post-GFC period. This shows that India’s capital account has become significantly more open in the last decade compared the first half of our sample period (1999-2009). This is also evident from Figure 1, which shows that over time the CIP deviation has become smaller, and more tightly distributed around zero. We show a summary of each of the six sub-periods in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary statistics of sub-periods of CIP deviations

|

Sub-period |

Start date |

End date |

Number of observations |

Median CIP deviation (%) |

Mean (average) CIP deviation (%) |

Standard deviation |

|

I |

18 August 1999 |

22 October 2002 |

829 |

-3.10 |

-3.73 |

3.24 |

|

II |

22 October 2002 |

11 August 2005 |

732 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

2.97 |

|

III |

11 August 2005 |

21 August 2009 |

1046 |

-3.34 |

-3.79 |

5.53 |

|

IV |

12 August 2009 |

3 February 2014 |

1161 |

0.35 |

0.02 |

3.96 |

|

V |

3 February 2014 |

15 February 2018 |

1052 |

1.18 |

1.12 |

2.03 |

|

VI |

15 February 2018 |

20 January 2021 |

763 |

-0.46 |

-0.94 |

2.76 |

We also determine the ‘no-arbitrage bands’ to get an estimate of the transactions costs12. The narrowing width of the no-arbitrage bands across the six sub-periods is consistent with our finding of greater financial integration over time.

Policy implications

Our findings are critical for policymaking especially in the context of monetary policy. If arbitrage between the domestic and foreign markets is perfect, that is, if the Indian financial markets are fully integrated with the global markets, then according to the CIP condition, the domestic interest rate equals the sum of foreign interest rates and expected currency depreciation. If the rupee is pegged to the foreign currency, then the expected depreciation component becomes zero, which means domestic interest rates cannot deviate from foreign interest rates. This implies that the Central Bank can either set the domestic interest rate and let the rupee float, or it can peg the exchange rate and give up control over the interest rate, which is the classic ‘Impossible Trilemma’13 implication.

However, if the arbitrage is imperfect and India’s capital account is not fully open, then the Central Bank can target both the exchange rate and the interest rate but this choice will prove to be costly – intervening in the foreign exchange market to target the exchange rate will increase the domestic money supply, thereby fuelling inflation. This means that currency intervention would need to be ‘sterilised’ by selling government bonds but that, in turn, imposes an interest burden on the government and worsens its fiscal position.

Our study indicates that India’s capital account has indeed become more open over time. This means that there would be greater inflows of foreign investment in response to any increase in the domestic interest rate by the RBI. At the same time, as an inflation-targeting central bank, the RBI must respond to inflationary risks by raising the interest rate. In other words, increasing financial integration with the rest of the world, along with increased monetary policy autonomy that is required to successfully pursue an inflation target, reduces the policy space available to the RBI to stabilise currency fluctuations.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content

Notes:

- Full capital account convertibility implies that agents can freely borrow or lend in international capital markets at the world real interest rate.

- See for example, Pandey et al. (2021), Pandey et al. 2020, Sengupta and Sen Gupta (2014), Hutchison et al. (2012), Shah and Patnaik (2008), among others, for a description of India’s capital controls regime.

- As outlined by the RBI, capital controls can primarily be defined as direct or administrative controls, and indirect or market-based controls. Direct controls restrict capital account transactions and associated payments or transfer of funds through outright prohibitions, explicit quantitative limits, or an approval procedure. Administrative controls seek to affect the volume of the relevant cross-border financial transactions (for example FDI (foreign direct investment), portfolio investment). Indirect controls discourage capital movements and the associated transactions by making them more costly to undertake.

- So far in the literature, capital control restrictions on external commercial borrowings of Indian companies (Pandey et al. 2021), and on foreign portfolio investments (Pandey et al. 2020) have been documented and we use this information to better understand the patterns of financial liberalisation during our sample period.

- Forward rate refers to the decided rate at which a bank agrees to carry out a future transaction, and spot rate is the rate quoted for an immediate transaction.

- For more details, see RBI (2020).

- An NDF is similar to a regular forward foreign exchange contract. The main difference is that an NDF does not involve a physical settlement of the contract and exchange of currencies. The underlying premise is that NDF contracts are traded on currencies that are not deliverable offshore. Due to the periodic and frequent changes in capital account restrictions by the Indian authorities, international participants engaged in cross-border transactions are unable to obtain easy access to the onshore currency market to either hedge their exposures to the rupee or to speculate on currency movements. Consequently, over the years a vibrant offshore NDF market has developed. The NDF market is free of capital controls, which makes it a good candidate for capturing the market implied interest rates, especially when the NDF market in rupee is liquid. The US dollar-Indian rupee currency pair has one of the largest NDF markets in the world.

- In finance, basis points is a common unit of measure and refers to 1/100th of a percentage point.

- The magnitudes of CIP deviations are evaluated on a relative scale, with a lower (absolute) magnitude of deviation indicating relatively greater openness of the capital account. In perfectly open markets, the size of the CIP deviations should be zero; however because of transactions costs, these deviations may not be zero. To estimate the size of transaction costs, we use time series methods. For more details, please refer to Aggarwal et al. (2021).

- The Taper Tantrum of 2013 refers to the large-scale reversal in foreign investment inflows in emerging economies such as India as a result of the assumption that the US Federal Reserve was planning to ‘taper’ their bond purchasing programme of quantitative easing.

- In 2019, a committee appointed by the RBI suggested several measures to curb the rising influence of the offshore INR markets, and to improve ease of access to the onshore markets (Thorat 2016). Subsequently, several of the committee’s recommendations were accepted and implemented during the course of 2020, some of which may qualify as capital account relaxations.

- The presence of transaction costs and capital controls result in the formation of bands around the CIP deviations within which arbitrage is not possible. Outside these bands, however, there are arbitrage opportunities and in the presence of a liquid foreign exchange market, the force of arbitrage would bring back the deviations within the no-arbitrage boundaries. With gradual relaxation of capital controls, the width of these no-arbitrage bands would reduce.

- The Impossible Trilemma suggests that it is it is impossible to have a fixed foreign exchange rate, free capital movement, and an independent monetary policy – at the same time.

Further Reading

- Aggarwal, N, S Arora, and R Sengupta (2021), ‘Capital account liberalisation in a large emerging economy: An analysis of onshore-offshore arbitrage’, IGIDR Working Paper.

- Hutchison, Michael M, Gurnain Kaur Pasricha and Nirvikar Singh (2012), “Effectiveness of Capital Controls in India: Evidence from the Offshore NDF Market”, IMF Economic Review, 60(3): 395-438. Available here.

- Pandey, Radhika, Gurnain Pasricha, Ila Patnaik and Ajay Shah (2021), “Motivations for capital controls and their effectiveness”, International Journal of Financial Economics, 26: 391-415. Available here.

- Pandey, Radhika, Rajeswari Sengupta, Aatmin Shah and Bhargavi Zaveri (2020), “Legal restrictions on foreign institutional investors in a large, emerging economy: a comprehensive dataset”, Data in Brief, 28: 104819. Available here.

- RBI (2020), ‘Onshoring the Offshore’, RBI Bulletin (August).

- Sengupta, R and AS Gupta (2014), ‘Policy Tradeoffs in an Open Economy and the Role of G-20 in Global Macroeconomic Policy Coordination’, in M Callaghan, C Ghate, S Pickford and FX Rathinam (eds.), Global Cooperation Among G20 Countries.

- Shah, A and I Patnaik (2008), ‘Managing Capital Flows: The Case of India’, ADB Institute Working Paper 98.

- Thorat, U, ‘Report of the Task Force on Offshore Rupee Markets’, Technical Report, Reserve Bank of India.

16 July, 2021

16 July, 2021

By: Rajeswari Sengupta 03 August, 2021

Many thanks for your comment. At the heart of any measure of CIP deviation is a forward market rate. We are using the offshore non-deliverable forward rate because the offshore market is significantly more liquid and well-traded compared to the onshore forward market (Ma et al. 2004, Hutchison et al. 2012). Other than that nothing changes in the imeasurement of the CIP deviations nor does anything get altered in the interpretation. Our use of the NDF rate doesn't imply that we are measuring only the deviation between the onshore market and only that particular offshore market. The participants in the NDF market are foreign investors from all over the world who are using the NDF market to hedge their exposures to the Rupee. Capital account restrictions aim to sever the links between domestic and foreign financial markets. So, if we see that these links are actually growing i.e. CIP deviations are narrowing, this shows that capital account restrictions are becoming less effective. There is also enough evidence by now in the literature that capital controls are not effective. RBI's attempts to onshore the offshore are quite recent (Jan-June 2020), in the aftermath of the Thorat Committee Report, whereas we find that CIP deviations have been narrowing roughly from 2015 onwards. This implies that India's capital account has relatively become more open now than in the pre 2010 period, but this does not mean that India has achieved 100% capital account convertibility. References: Hutchison, Michael M, Gurnain Kaur Pasricha and Nirvikar Singh (2012), “Effectiveness of Capital Controls in India: Evidence from the Offshore NDF Market”, IMF Economic Review, 60(3): 395-438. Ma, G., C. Ho, and R. McCauley, (2004), “The Markets for Non-Deliverable Forwards in Asian Currencies,” BIS Quarterly Review (June), pp. 81–94.