The last few years have seen the growth of a private credit market in India, which offers financing to small and mid-sized firms with a relatively high default risk. In this piece, Datta and Sengupta discuss the emergence of alternative investment funds in the context of the evolving commercial credit landscape. They touch upon some of the regulatory challenges presented by these funds, and how such a credit market can relieve some of the pressure faced by the banking system.

Worldwide, non-financial companies typically depend on debt capital from banks or bond markets, or equity capital from public or private markets for external financing. This is especially the case for large, established companies. Over the last few years, this landscape has been witnessing a new development – the emergence of the ‘private credit market’. Private credit refers to non-bank debt financing in high yielding and illiquid investments using debt-like instruments, which are extended primarily to small and mid-sized firms with relatively high default risk that are not able to access the traditional sources of financing. This debt does not have a readily tradeable market or publicly quoted price and is originated or held by non-bank lenders. As in the rest of the world, private credit in India is offered to mid-market firms which are underserved by traditional sources of capital (EY, 2021).

On several dimensions, private debt funds are closer to private equity funds in that they have a similar investor base, and relatively high return expectations (Block et al. 2023). Globally, this market has become prominent since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis as banks came under stricter capital requirement norms, which pushed them away from lending to smaller or riskier borrowers. Since then, this trend has been picking up pace both in developed and emerging economies. Although this form of credit has always existed through non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) and mutual funds (MFs), alternative investment funds (AIFs) that operate in the private credit space are a relatively new phenomenon in the Indian credit landscape.

The Indian credit market has undergone a tectonic shift over the last decade, opening up new opportunities in the private credit space. The prolonged period of balance sheet stress in the banking sector that manifested as high levels of non-performing assets (NPAs) from roughly 2013 to 2019, and the crisis in the NBFC sector triggered by the default of IL&FS (Infrastructure Leasing and Financial Services) in September 2018, pushed the traditional institutional sources of corporate finance towards retail lending. This financing void, among other factors, provided an opportunity for the AIFs that operate in the private credit space. The enactment of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), 2016, arguably, was also an important factor that supported the development of the AIF-driven private credit market in India. In fact, this may be considered one of the most inspiring success stories of the corporate insolvency law reforms since 2016. In this piece, we analyse the evolution of the private credit market in India, discuss the advantages of developing this market, and highlight some challenges.

Changes in the commercial credit landscape

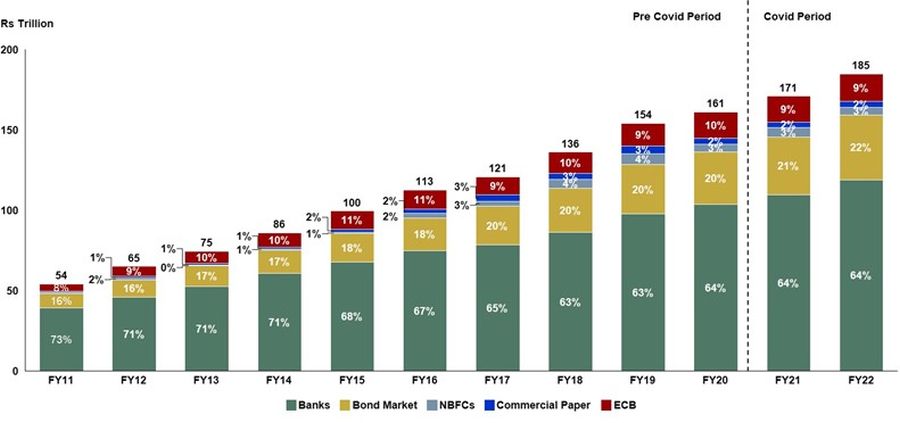

One of the most significant trends in the contemporary Indian credit landscape has been the decline in the growth of commercial (non-government) credit. Total commercial credit growth declined from 16.4% in 2011-2015 to 10.1% in 2015-2020. Figure 1 shows the evolution of the shares of the traditional credit sources over the period from 2011 to 2022. Historically, banks have been the largest providers of commercial credit in India. During the last decade, their share in total commercial credit fell from a peak of 73% in 2011 to 64% in 2022. Corporate bond issuances and NBFCs filled the gap created by the shrinking of bank credit.

Figure 1. Shares of various credit sources in total credit, 2011-2022

Source: Sengupta and Vardhan (2023)

Note: i) Numbers on the y-axis depict the total amount lent, while the numbers on the stacks depict share in total credit. ii) Years are financial years ending March of that year. iii) Total credit refers to total commercial or non-government credit; credit by NBFCs is net of credit from banks and bond market to them.

One of the main reasons behind the decline in bank credit was the twin balance sheet (TBS) crisis, which manifested in the form of growing NPAs on the balance sheets of inadequately capitalised banks and high levels of debt in financially stressed companies in the private corporate sector (Government of India, 2017, Sengupta and Vardhan 2019). To deal with the TBS crisis, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) introduced the Asset Quality Review (AQR) programme in FY2015-16 which forced the banks to recognise the NPAs on their balance sheets. The actions taken by the RBI and the government triggered risk aversion in the banking system (Sengupta and Vardhan 2023). It also led to a decline in the share of industrial credit in total bank credit. Banks withdrew from lending to the private corporate sector and instead began focusing on lending to the retail sector. Consumer credit as a share of total bank credit went up remarkably from 19% in 2011 to 30% in 2020, causing a trend of ‘consumerisation of credit’ in Indian banking during this period (Sengupta and Vardhan 2021).

Between 2011-2015 and 2015-2020, the growth rate of credit from NBFCs went up sharply from 5% to nearly 45%. However, the NBFC sector faced a big blow with the default of IL&FS in September 2018, which sent shockwaves through the banking system as well as the debt markets – the two biggest funding sources for NBFCs. This was followed by other relatively low-impact shocks due to problems in the financial sector such as DHFL (Dewan Housing and Finance Limited) and IndiaBulls Housing Finance, as well as in Yes Bank. These events further worsened the risk appetite of the banks and triggered risk aversion in the debt markets as well (Sengupta and Vardhan 2023).

By the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, bank credit growth reached a decade low of barely 6%. By the time the pandemic subsided and as the Indian economy began recovering from the shock, the health of the banking sector also improved substantially. Successive waves of recapitalisation by the government gave the public sector banks enough resources to write off most of their bad loans. The resumption of bank credit growth, however, has been primarily driven by growth in unsecured consumer credit and home loans, and to some extent by MSME credit. The growth rate of bank loans to industry fell to from close to 10% in FY2021-22 to 4.9% in FY2022-23 (Reserve Bank of India, 2023).

Evolution of AIFs

This broader trend in the credit landscape as described above created a conducive environment for the emergence of AIFs in India, especially over the last five to six years. A growing amount of capital is now being invested in bonds through these credit AIFs (which under the SEBI nomenclature are called AIF Category II). This signals the emergence of a private credit market.

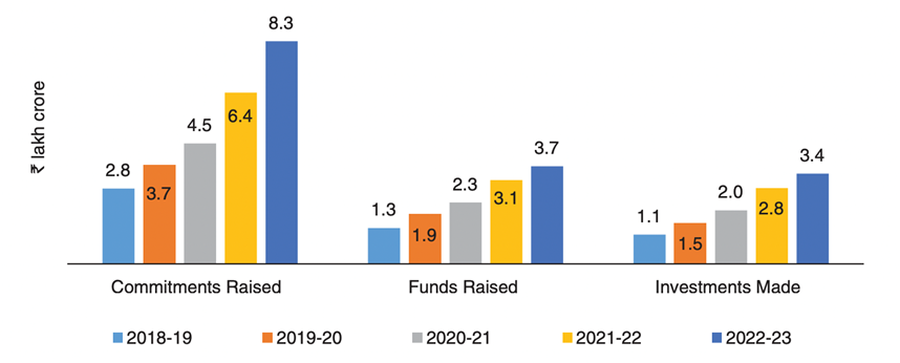

Over the last few years AIFs have been one of the most rapidly growing segments in the credit landscape. As shown in Figure 2, AIFs have seen significant growth in terms of commitments raised, funds raised, and investments made since FY2018-19. Category II AIFs, which include funds for distressed assets, accounted for 73% of the overall funds raised by AIFs (Securities and Exchange Board of India, 2023).

Figure 2. Growing AIF ecosystem in India

Source: Securities and Exchange Board of India

AIFs deploy funds across various instruments such as unlisted equity shares/equity linked instruments/Limited Liability Partnership interest, listed equity, debt/securitised debt instruments, units of other AIFs, liquid funds, listed/to be listed securities on SME Exchange etc. Debt and securitised debt instruments received the second largest amount of investment from AIFs between 2020 to 2023, second only to unlisted equity shares and equity linked instruments.

While the exact ‘assets under management’ of credit AIFs are not publicly available, they are estimated to be about Rs. 1 to 1.5 trillion. Despite being a small percentage of the total credit, they are performing a very important role in widening the issuer base of bonds. Arguably, AIFs provide a better model for wholesale credit compared to the NBFCs whose inherent fragilities arise from asset liability mismatches on their balance sheets. As a result of the growing presence and penetration of the AIFs, better risk distribution and capital allocation through the markets might take place.

Challenges arising from a private credit market

While these funds can perform a critical role – that of developing the bond market for lower rated securities – they also present a different kind of regulatory challenge. Credit AIFs in India are quite small in size at present, and hence they have not yet attracted enough regulatory attention, though that seems to be changing in recent times. Currently, credit AIFs get clubbed in the AIF Category II along with private equity funds, and their corpus is not separately reported. Since the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) started regulating AIFs in 2012, there have been 24 amendments to the SEBI (AIF) Regulations, 2012. 75% of these amendments were made since 2020. These amendments have focused on improving governance and transparency of AIFs as well as investor protection. Going ahead, regulators will have to encourage the development of these funds so that the bond market becomes deeper.

At the same time, risks arising from this market will need to be better understood, monitored and managed through norms on governance, reporting, disclosures, and so on. This process has already begun. For instance, to prevent ever-greening of loans (that is, issuing new loans to avoid default on existing ones) through AIFs, the RBI recently restricted its regulated entities (like banks and NBFCs) from substituting their direct loan exposure to borrowers with indirect exposure through investments in units of AIFs (Reserve Bank of India, 2023). In parallel, SEBI has issued a consultation paper proposing regulations aimed at preventing AIFs from circumventing extant financial sector regulations such as foreign exchange regulations and regulations pertaining to quota for Qualified Institutional Buyers in Initial Public Offerings (Securities and Exchange Board of India, 2024). We therefore believe that the private credit market will experience enhanced regulations in the near future.

It is also important to recognise that, apart from the withdrawal of banking sector from industrial credit and the skew of the corporate bond market towards high rated companies, another factor that may have played a critical role in the rise of the AIF-driven private credit market in India was the enactment of the IBC in 2016. Unlike banks and NBFCs, AIF lenders are not legally allowed to use the enforcement rights under the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act (SARFAESI Act), 2002.1 AIFs also cannot use the RBI’s out-of-court restructuring mechanism.2 The primary statutory instrument that effectively safeguards AIFs’ interests in loans or debt investments in companies is the IBC. Consequently, the AIF-driven private credit markets will benefit enormously from a better functioning corporate insolvency law regime.

Policymakers appear to have also recognised the virtuous relationship between AIFs and the corporate insolvency regime. Traditionally, Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) were the only players allowed to purchase stressed corporate loans from lenders such as banks, NBFCs and other financial institutions. In January 2022, SEBI introduced a special sub-category of AIFs, namely Special Situation Funds (SSFs), which can purchase special situation assets, including stressed loans, in terms of Regulation 58 of RBI (Transfer of Loan Exposure) Directions 2021. Although these regulations are likely to be fine-tuned in the near future, SSFs have the potential to improve the recovery rate for lenders using the IBC, enabling the creation of a vibrant stressed assets market in India (Datta 2022).

Conclusion

Although this is a relatively new phenomenon in the Indian private credit market, AIFs are emerging as reliable suppliers of patient and flexible debt capital to mid-market, lower rated companies. If this private credit market flourishes, it may relieve some of the pressure faced by the overburdened banking system and may encourage commercial banks to undertake better allocation of capital, perhaps more targeted to the retail sector. This can eventually lead to the emergence of a credit landscape in India where large, highly rated companies directly access debt capital through the corporate bond market, the vast majority of medium and small sized, lower rated companies access debt capital through the AIFs, and the banking system predominantly caters to the retail sector.

The views expressed in this post are solely those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of the I4I Editorial Board.

Notes:

- ‘Financial institutions’ as defined in section 2(1)(m) of SARFAESI Act, 2002 can use the enforcement rights under that statute. AIFs are not covered in this definition.

- AIFs are not covered within the definition of ‘lender’ under this circular (Reserve Bank of India, 2019).

Further Reading

- Block, J, YS Jang, SN Kaplan and A Schulze (2023), ‘A Survey of Private Debt Funds’, NBER Working Paper 30868.

- Datta, P (2022), ‘Why special situation funds are necessary’, Indian Express, 16 March.

- EY (2021), ‘Evolution of Private Credit in India, November 2021’, White Paper.

- Government of India (2017), ‘The Festering Twin Balance Sheet Problem’, Chapter in Economic Survey 2016-17 (available here).

- Reserve Bank of India (2019), ‘Prudential Framework for Resolution of Stressed Assets’, Circular.

- Reserve Bank of India (2023), ‘Investments in Alternative Investment Funds (AIFs)’, Circular.

- Securities and Exchange Board of India (2023), ‘Annual Report 2022-23’.

- Securities and Exchange Board of India (2024), ‘Consultation paper on proposal to enhance trust in the Alternative Investment Funds (‘AIF’) ecosystem to facilitate Ease of Doing Business measures’.

- Sengupta, R and H Vardhan (2019), ‘Banking crisis impedes India’s economy’, East Asia Forum, 3 October.

- Sengupta, R and H Vardhan (2021), ‘‘Consumerisation’ of banking in India: Cyclical or structural?’, Ideas for India, 23 July.

- Sengupta, R and H Vardhan (2023), ‘India’s Credit Landscape in a Post-pandemic World’, in M Das and I Gupta (eds.), Contextualizing the COVID Pandemic in India- A Development Perspective, Springer.

30 January, 2024

30 January, 2024

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.