Since the turn of the century, income inequality has risen to be among the most prominent policy issues of our time. This column looks at inequality trends in recent decades. While relative global inequality has fallen, insufficient economic convergence, together with substantial growth in per capita incomes, has resulted in increased absolute inequality since the mid-1970s. The inclusivity aspect of growth is now more imperative than ever.

Since the turn of the century, inequality in the distribution of income, together with concerns over the pace and nature of globalisation, have risen to be among the most prominent policy issues of our time. These concerns took centre stage at the annual G20 summit in China in September 2016. From President Obama to President Xi, there was broad agreement that the global economy needs more inclusive and sustainable growth, where the economic pie increases in size and is at the same time divided more fairly. As President Obama emphasised, “[t]he international order is under strain.” The consensus is well founded, following as it does the recent Brexit vote, and the rise of populism (especially on the right) in the US and Europe, with its hard stance against free trade agreements, capital flows and migration.

Watch Finn Tarp and Miguel Niño-Zarazúa discuss the trends in global inequality in the video below:

These are clear manifestations of a growing discontent among the working middle classes, particularly in the industrialised world, who see globalisation as the primary source of growing inequalities, and an obstacle to their prosperity. These views have no doubt been fuelled in large part by the Global Crisis of 2008-09 and the Great Recession that followed immediately afterwards. However, in reality, concerns about inequality are not new. From Plato and Aristotle to classical economists such as Adam Smith and Karl Marx, some of history's greatest thinkers have stressed the undesirable effects of inequality on the social fabric. Not only are high levels of inequality widely perceived to be socially unfair, as present events are making abundantly clear, they also have negative implications for political stability (Alesina and Perotti 1996), crime (Kelly 2000), and corruption (Jong-sung and Khagram 2005), among other things. It is now also understood that inequality reduces the efficacy of economic growth for reducing poverty (Ravallion 2001).

So what has actually happened to global inequality? Has global income inequality gone up (or down) in recent decades?

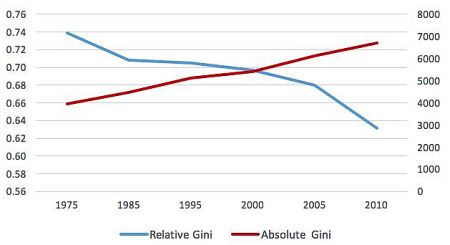

In a recent paper, we show that relative global inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, declined steadily over the past few decades from 0.739 in 1975 to 0.631 in 2010 (Niño-Zarazúa et al. 2016). The relative Gini takes the value zero for a society where all are equal, and the value of one for a society where all income goes to one person. The fall over the past 35 years (that is, the blue line in Figure 1) was driven primarily by declining inequality between countries, arising from the extraordinary economic progress observed in fast-developing countries such as India and China. And this overall trend was achieved despite an increasing trend of inequality within countries. In contrast, absolute inequality, as measured by the absolute Gini coefficient, which is based on absolute changes in income, and depicted by the red line in Figure 1, has increased dramatically since the mid-1970s.

Figure 1. Trends in global inequality from a relative and absolute perspective

'Relative' versus 'absolute' inequality

What's the difference between 'relative' and 'absolute' inequality, and which trend is more important? As one of us (Finn Tarp) recently explained in an interview, take the case of two people in Vietnam in 1986. One person had an income of US$1 a day and the other person had an income of $10 a day. With the kind of economic growth that Vietnam has seen over the past 30 years, the first person would now in 2016 have US$8 a day, while the second person would have US$80 a day. So if we focus on 'absolute' differences, inequality has gone up, while a focus on 'relative' differences suggests that inequality between these two people has remained the same.

Relative inequality indicators have been by far the most widely used in empirical economic analysis, but, based on economic theory and empirical evidence, it is far from clear that we should favour relative over absolute notions of inequality. The evidence suggests that many people do perceive absolute differences in incomes as being an important aspect of inequality (Amiel and Cowell 1992, 1999).

What has happened across world regions?

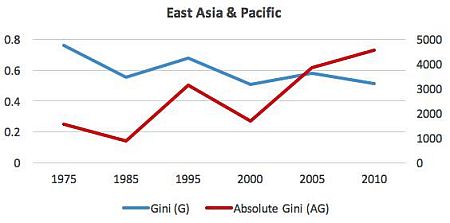

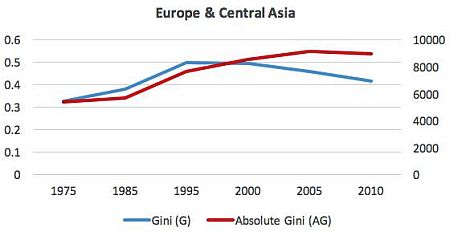

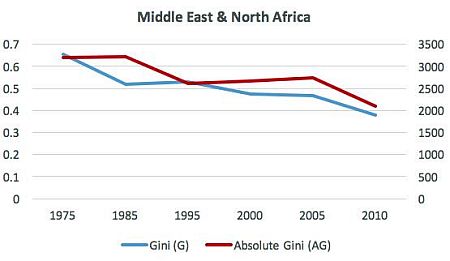

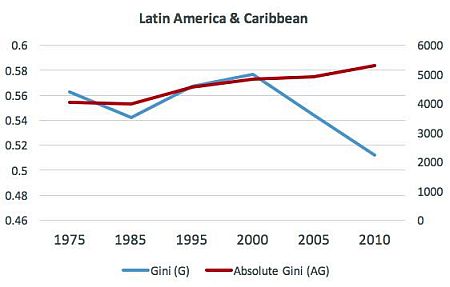

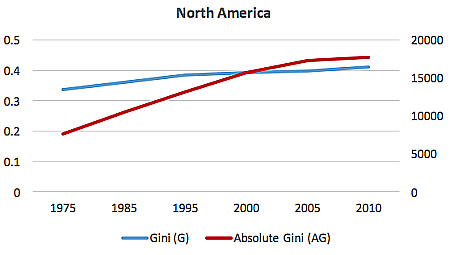

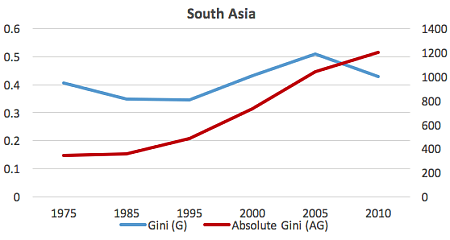

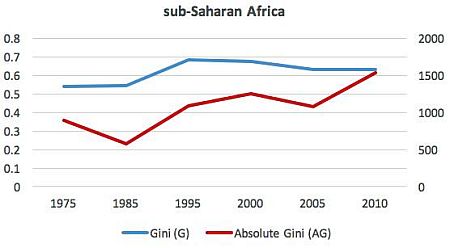

In contrast to the clear trends in global inequality, we found substantial differences in trends across the different regions of the world. For example, Figure 2 shows that inequality, both relative and absolute, increased substantially and steadily throughout 1975–2010 in North America, and also in Europe and Central Asia, South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, though with some ups and downs along the way according to relative inequality measures. Absolute inequality rose in Latin America, East Asia, and the Pacific, while relative inequality fell.

Figure 2. Regional relative and absolute inequality

We also observed considerable variation within regions with respect to levels of, and changes in, domestic inequality over the period of analysis. For example, in Europe, the UK experienced an increase in relative inequality of 38%, while France saw a reduction of 16%; in Latin America, relative inequality in Argentina increased by 25%, while Brazil managed a reduction of 10%; in South Asia, Bangladesh experienced an increase of 60%, while Nepal saw a reduction of 38%.

Could the increased absolute global inequality have been prevented while achieving the same rates of economic growth observed in the past 40 years?

Declining relative inequality between countries, driven by the emergence of India and China as economic powerhouses, has, as noted, been the main factor in reducing global relative inequality. Yet insufficient economic convergence, together with substantial growth in per capita incomes, has meant that the increased absolute differences in average incomes between countries have resulted in increased absolute global inequality. Could this increased absolute inequality have been avoided, while maintaining the same economic growth that has lifted many millions of people in poorer countries out of poverty?

The answer is not straightforward. There are both technical considerations and issues of political economy associated with this question. As can be inferred from a paper by one of us (Roope 2015), economic growth of the magnitude observed in the past four decades, together with falling absolute inequality, is technically possible. However, as we demonstrate in our latest study, at current national levels of per capita incomes, without even greater convergence among countries, the answer is no (Niño-Zarazúa et al. 2016). Although average incomes in large developing countries are now much closer proportionally to those in high-income countries, the absolute gaps in income between countries are so high that even if domestic inequality were completely eliminated in all countries (which is obviously impossible), absolute inequality today would still be much higher than it was 40 years ago. Thus, while redistributive policies and investment in public goods like health and education are likely to mitigate both types of inequality, further convergence among countries is essential to bring global absolute inequality down to the levels seen before the recent era of globalisation.

Thus, it is, in our judgement, necessary to exercise care when discussing reducing absolute inequality, especially in poor countries. Over the past 40 years, over one billion people around the world have been lifted out of poverty, driven largely by substantial growth in income in developing countries. While this growth has been accompanied by a striking rise in absolute inequality, it has also improved the lives of hundreds of millions of people. It is difficult to imagine how in practice such growth, and the associated poverty reduction, could have occurred without an increase in absolute inequality. There would be huge implications for the fight against global poverty if attempts were made to halt economic growth in order to appease absolute inequality. Instead, the policy emphasis should be on creating more inclusive growth with falling 'relative' inequality – these two goals are complementary.

The inclusivity aspect of growth is now more imperative than ever. Globalisation has not been a zero-sum game. Overall perhaps more have benefitted, especially in fast-growing economies in the developing world. However, many others, for example among the working middle class in industrialised nations, have seen their incomes stagnating in real terms for over 20 years. It is unsurprising that this has bred considerable discontent, and it is an urgent priority that concrete steps are taken to reduce the underlying sources of this discontent. Those who feel they have not benefitted, and those who have even lost from globalisation, have legitimate reasons for their discontent. Appropriate action will require not only the provision of social protection to the poorest and most vulnerable. It is essential that the very nature of the ongoing processes of globalisation, growth, and economic transformation are scrutinised, and that broad-based investments are made in education, skills, and health, particularly among relatively disadvantaged groups. Only in this way will the world experience sustained – and sustainable – economic growth and the convergence of nations in the years to come.

This article is reproduced by permission of UNU-WIDER, which commissioned the original research and holds copyright thereon.

Further Reading

- Alesina, Alberto and Roberto Perotti (1996), "Income distribution, political instability, and investment", European Economic Review, 40(6):1203-1228. Available here.

- Amiel, Yoram and Frank A Cowell (1992), "Measurement of income inequality", Journal of Public Economics, 47(1):3-26. Available here.

- Amiel, Y and FA Cowell (1999), Thinking about inequality: Personal judgment and income distributions, Cambridge University Press. Available here.

- Jong-sung, You and Sanjeev Khagram (2005), "A comparative study of inequality and corruption", American Sociological Review, 70(1):136-157. Available here.

- Kelly, Morgan (2000), "Inequality and crime", Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(4):530-539. Available here.

- Niño-Zarazúa, Miguel, Laurence Roope and Finn Tarp (2016), "Global inequality: Relatively lower, absolutely higher", Review of Income and Wealth. Available here.

- Ravallion, Martin (2001), "Growth, inequality and poverty: Looking beyond averages", World Development, 29(11):1803-1815.

- Roope, L (2015), 'Critical percentiles for equalizing growth', Centre for the Study of African Economies (CSAE) Working Paper, University of Oxford.

17 February, 2017

17 February, 2017

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.