A multidisciplinary literature – mostly focused on the US – shows that choice of majors among college students is gendered, and females are particularly under-represented in math-intensive fields. Based on survey and administrative data from India, this article presents evidence of the disproportionately low enrolment of women in science and economics, despite the large earnings premium to studying these subjects. It highlights the importance of large gender differences in preferences over various attributes of college majors and jobs, and in the expectations of future outcomes associated with choice of majors.

A multidisciplinary literature – spanning economics, psychology, and sociology – studies the gendered enrolment of college students into majors, with a focus on the under-representation of women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) fields. However, much of this research pertains to the US. Given that local cultural norms may influence educational choices, we investigate the following in the context of a large developing country, India (Dasgupta and Sharma 2020): first, is there an earnings premium associated with studying subjects like STEM in college, compared to other majors, and if so, does this earnings premium exist for women as well? Second, how do students decide what major to study and what is the relative importance of ‘preferences’ (over attributes of college majors and jobs) and ‘expectations’ (about future outcomes conditional on graduating in a particular major) in explaining the gender differences in enrolment into various majors in college. For example, women may prefer jobs that allow for greater work-life balance, while men may prefer jobs that have higher earnings. Women may believe they are more likely to get higher grades if they study humanities rather than STEM, while men believe they are more likely to gain parental approval for their college major choices if they study STEM. We collect subjective expectations data from both women and men to quantify the role of preferences and expectations. To our knowledge, our study is the first to collect such subjective expectations data and to examine choice of college majors in the context of a developing country.

We answer these questions by analysing novel data from two surveys that we conducted – one of high-earning young professionals educated in elite institutions across the country, whose median earnings is five times the national per capita income, and the other of undergraduate students enrolled in a private university near Delhi, many of whom will go on to work in high-paying jobs. This is a demographic group of interest for a number of reasons: a narrowing of the gender gap at the top of the earnings distribution has been found to be associated with an increase in promotions among women in the workplace (Matsa and Miller 2011), and even an improvement in firm performance (Smith et al. 2006). Moreover, gender inequality is likely to be lower at higher levels of income because of relatively progressive social norms (World Bank 2012), which implies that evidence of gender inequality in this sample would reflect serious concerns about the pervasiveness of structural gender disadvantage.

Returns to studying STEM or economics in college

To answer the first question, we study a group of 326 comparable students (from the first survey) who have all completed the same graduate programme during 2010-2018, but hold different undergraduate degrees across STEM, economics and business, and the humanities and social sciences. We survey them on their educational and job histories, collect measures of their personality traits, and combine this with rich administrative data from their university.

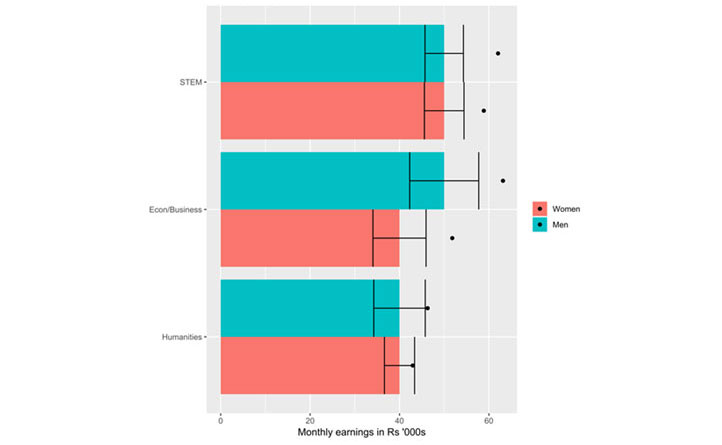

Figure 1a shows the (unconditional) relationship between college major and earnings. The highest earnings accrue to STEM, followed by economics, and then the humanities. While women earn the same premium from studying STEM subjects as men do, the earnings gap between men and women is significant only for economics graduates. In a more formal regression analysis, even after accounting for a rich set of individual characteristics – cognitive, non-cognitive, social and demographic characteristics, and personality traits – we find large economic returns ranging from 17% to 32% to college majors in STEM and economics, relative to social science and the humanities. Accounting for choice of college majors reduces the overall earnings premium of men by as much as a fifth. We also find that occupational choice is a key driver of differences in earnings across genders and choice of college majors, with STEM and economics majors dominating the higher-paying occupations, and men outnumbering women in these majors.

Figure 1a. Relationship between college major and earnings, by gender

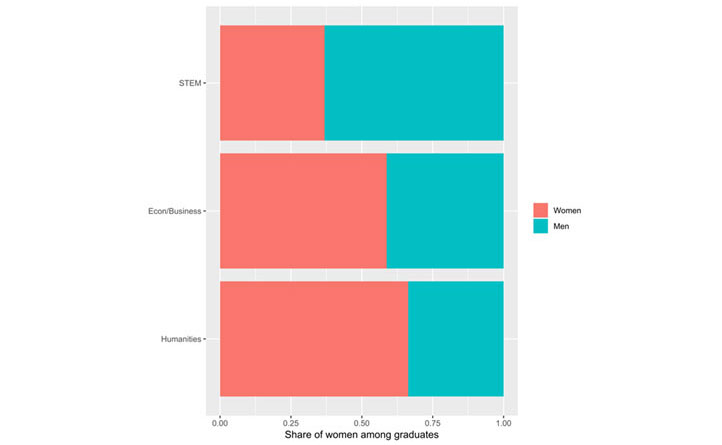

Figure 1b. Share of women among college graduates, by majors

Despite these high returns to studying science, we find that only 39% of women graduates in our survey have STEM degrees, almost half the proportion of men at 68%, while 35% of women graduates study the humanities, more than double the proportion of men at 16% (Figure 1b). We turn next to explaining the low enrolment of women in STEM and economics degrees.

How do students decide what major to study in college?

To answer the second question, we estimate a model of choice of college major, by surveying a sample of 351 undergraduate students who are in the process of deciding what major to study. Following Zafar (2013), and Wiswall and Zafar (2015, 2017), we collect information on students’ subjective expectations of their outcomes in college and in the labour market, conditional on their choice of major, and use these data to estimate models of major choice by gender. Students were asked to rank their preferred major choices across four categories (STEM, economics, social sciences, and the humanities), and were asked a series of questions eliciting their subjective expectations about outcomes associated with graduating in each major. The outcomes included characteristics of the majors (probability of getting high grades, hours per week spent studying, probability of enjoying the degree, probability that parents will approve of the choice), and job characteristics (expected earnings right after graduation, expected earnings 10 years after graduation, probability of employment, probability of employment in preferred sector, probability of having a gender-balanced workplace, probability of enjoying work-life balance). For example, students were asked what they thought the probability was that they would get a GPA of at least 3.3/4 conditional on graduating in each of the four categories of majors. Similarly, they were asked what they expected their average earnings to be, again conditional on graduating in each of the four categories of majors.

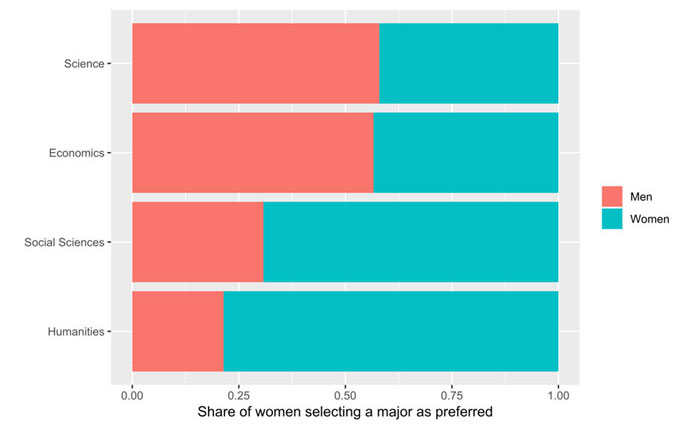

Figure 2 below shows substantial gender differences in the ranking of college majors. More than half of the women prefer a major in social science or the humanities, compared to 26% of men. Correspondingly, three quarters of the men prefer a major in science or in economics.

Figure 2. Gender differences in stated preferences over college majors

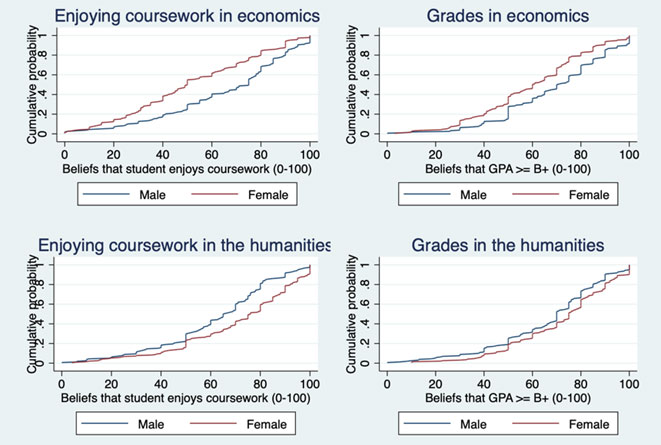

In terms of subjective expectations, there is a sharp gender divide across STEM and economics on the one hand, and social science and the humanities on the other. As an example, in Figure 3 men predict higher grades for themselves relative to women in STEM and economics, while women predict higher grades for themselves than men in social sciences and the humanities. For example, almost 60% of men believe there is at least a 50% chance of they will enjoy coursework in economics, compared to only 30% of women: in short, men have much higher expectations of enjoying coursework in economics. Similarly, women are much more likely to believe that they will enjoy studying the social sciences and the humanities compared to men. Stark gender differences are also visible in expectations about grades across college majors.

Figure 3. Gender differences in subjective expectations regarding enjoyment of coursework and expected grades, by college majors

We use these data to estimate models of choice of college majors, and quantify the relative importance of preferences over different attributes of majors and jobs and expectations about future outcomes, in determining gender differences in major choice. We find that while both matter, unlike in the US, a much higher share of the gender differences in enrolment (50-75%) can be explained by differences in expectations about future outcomes.

Among preferences, we find that women place a much greater weight on enjoying coursework and expected grades and a lower weight on expected earnings, as compared to men. Women are willing to forego 8.1% of expected earnings after graduation for a 1 percentage point increase in the probability that they would enjoy the coursework, and 5.1% of expected earnings for a 1 percentage point increase in the probability that they obtain an above-median grade. These estimates are twice as large as the corresponding estimates for men. These differences are most acute in the bottom half of the ability distribution: high-ability men and women are relatively similar to one another, but low-ability women appear to have very different preferences from low-ability men.

Working in a desired sector is also important, but job-related characteristics such as work-life balance and gender-balanced workspaces, are not found to be significant determinants of gender disparities in enrolment. Strikingly, women's expectations about their probability of employment in 10 years are no different than that of men. Women do not report foreseeing themselves as being more likely to be married or having children in the next 10 years compared to men, which, together with the insignificance of the preferences for work-life balance, suggest that a differential desire for flexible working hours or to later exit the workforce is not driving the results. Instead, other unobserved characteristics of jobs are clearly exerting an important influence on the choice of desired sectors.

Policy implications

Gender differences in preferences over college majors and jobs pose a particular challenge for policymakers who are aiming for greater gender equity in enrolment in higher education. Evidence from social psychology suggests that while there exist gender differences in interests in STEM, these are not hardwired in biology but are socially constructed and influenced by prevailing gender stereotypes, discrimination, and other cultural and social constraints on women seeking to enter these fields (Hyde 2014, Bertrand 2020).

The importance of expectations, relative to preferences, in determining choice of college majors – as shown in our study – has important policy implications as it might be easier to shift expectations about future outcomes than it is to change underlying preferences. In particular, we find that while all students struggle to predict their grades accurately, women are far more pessimistic about their grades than men, and this gap is particularly large when it comes to STEM and economics. Can these expectations be changed? Conlon (2019) finds that students respond to information they receive about the earnings distribution conditional on choice of college majors, by updating their earnings expectations and changing their choice of majors. Whether students respond the same way to information about grade distribution, leading to partly closing the gender gap in choice of college majors, is an area for future research.

Note:

- We surveyed 326 alumni of the Young India Fellowship programme at Ashoka University through an online survey conducted from July-September 2018 and combined this data with administrative data from the university.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Further Reading

- Bertrand, Marianne (2020), “Gender in the Twenty-First Century”, AEA Papers and Proceedings, 110: 1–24.

- Conlon, John J (2019), “Major Malfunction: A Field Experiment Correcting Undergraduates’ Beliefs about Salaries”, Journal of Human Resources, Forthcoming.

- Dasgupta, A and A Sharma (2020), ‘Preferences or expectations: Understanding the gender gap in major choice’, Working paper.

- Goldin, Claudia (2014), “A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter”, American Economic Review, 104(4): 1091–1119. Available here.

- Hyde, Janet Shibley (2014), “Gender Similarities and Differences”, Annual Review of Psychology, 65(1): 373–398.

- Matsa, David A and Amalia R Miller (2011), “Chipping away at the glass ceiling: Gender spillovers in corporate leadership”, American Economic Review, 101(3): 635-39.

- Smith, Nina, Valdemar Smith and Mette Verner (2006), “Do women in top management affect firm performance? A panel study of 2,500 Danish firms”, International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 55(7): 569-593. Available here.

- Wiswall, Matthew and Basit Zafar (2015), “Determinants of College Major Choice: Identification using an Information Experiment”, The Review of Economic Studies, 82(2): 791–824.

- Wiswall, Matthew and Basit Zafar (2017), “Preference for the workplace, investment in human capital, and gender”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(1): 457–507.

- World Bank (2012), ‘World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development’, Technical report, World Bank.

- Zafar, Basit (2013), “College major choice and the gender gap”, Journal of Human Resources, 48(3): 545–595.

23 October, 2020

23 October, 2020

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.