In the third post of a six part series on the estimation of poverty in India, Justin Sandefur considers the approaches employed for projections of poverty estimates since 2011-12 – the last year for which official estimates are available. He highlights the novel and creative solutions used by two recent working papers to fill the gap. But given other economic indicators and quality of National Accounts data, he expresses skepticism over the optimistic headline poverty figures proffered by both papers.

In the early 2000s, economists engaged in a heated debate about how much India's 1990 liberalisation had reduced poverty. Christening it ‘The Great Indian Poverty Debate’, Nobel Laureate Angus Deaton and Valerie Kozel noted "the various claims have often been frankly political, but there are also many important statistical issues" (Deaton and Kozel 2005). Twenty years later, history repeats.

No recent official data on poverty

The underlying question this time is whether Narendra Modi, who assumed office in 2014, has been good for poverty reduction. From a technical perspective, this debate is interesting because the data are so bad. If the data were good, there'd be no need for fancy imputations. But because the integrity of India’s statistical system has come into question over recent years, facts are up for grabs.

Official poverty measurement essentially stopped in 2011-12. There are hints of bad news behind that pause. Leaked data from the 2017-18 National Sample Survey (NSS) showed a startling 3.7% decline in real consumption over six years, and the survey was never released. Though in fairness, those preliminary numbers seemed implausibly dire (Felman et al. 2019).

In the absence of official survey data, two new papers released in April 2022 offered creative solutions to fill in the gaps, and reached starkly different conclusions about what might be happening to poverty.

Private survey data show poverty is higher than thought

Sutirtha Sinha Roy and Roy van der Weide (henceforth RW) use data from the Consumer Pyramid Household Survey (CPHS) run by the Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy to come up with a new estimate of Indian poverty. That's no small feat, since the official data stopped in 2011 and the CPHS only started in 2014, its sample appears to undercount poor households, and even small differences in how consumption questions are asked can make a big difference. So RW spend many pages explaining how they reweight the CPHS data to make it comparable to the NSS series – impressively painstaking work that I can't really do justice to here.

The end result, though, is cautiously optimistic. The title – “Poverty in India Has Declined over the Last Decade But Not As Much As Previously Thought” – really lives up to the frequent exhortation to researchers to "just say what you found". They make four basic claims:

i) Extreme poverty fell 12.3 percentage points from 2011 to 2019, using the World Bank’s $1.90 per day poverty line in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms.

ii) Poverty stood at 10.2% in 2019, considerably higher than earlier projections based on consumption growth observed in National Accounts.

iii) Urban poverty rose by 2 percentage points during the 2016 demonetisation, and rural poverty reduction stalled by 2019, when the economy slowed.

iv) Inequality has stopped rising since 2011.

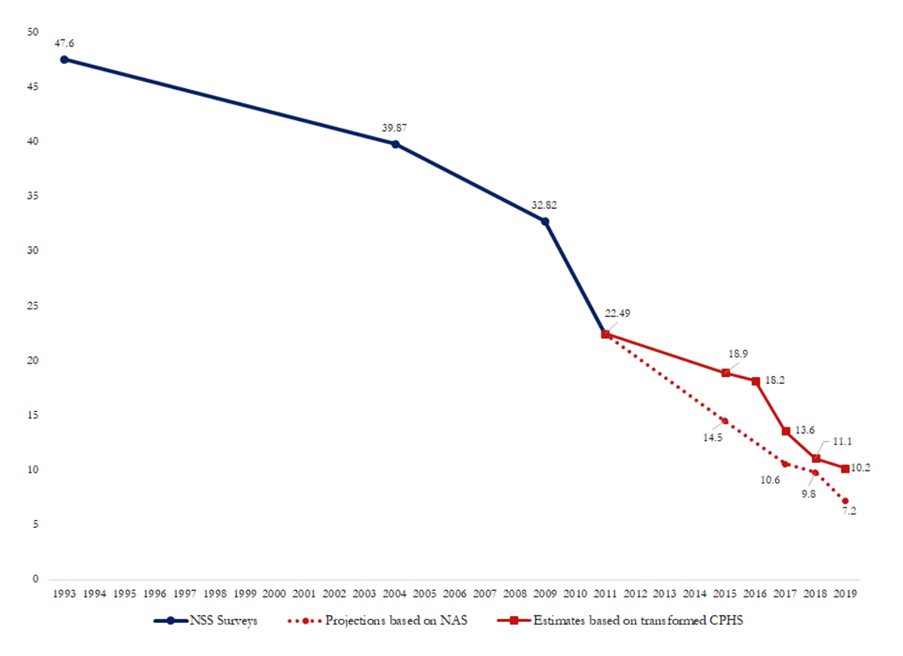

The basic story can be seen in the figure below: still good news, but less so than if you just relied on national accounts.

Figure 1. Indian poverty projections since the official data series stopped in 2011

Source: Roy and van der Weide 2022.

Notes: i) Poverty projections use the World Bank’s poverty line of $1.90 PPP per day. ii) The blue line indicates poverty rates according to data from NSS surveys; the solid red line indicates estimates based on transformed CPHS data, and the dotted red line indicates estimates based on the national accounts system.

There were good ex-ante reasons to think the projection based on the national accounts system in Figure 1 was too optimistic. However, consumption growth in the CPHS survey also looks surprisingly high in the latter years, especially 2019-20. That year, the index of industrial production for consumer goods registered an absolute decline of 3.8% (even more in per capita terms), real rural wages declined, and real urban wages grew less than 2% – meanwhile the CPHS showed growth in real per capita consumption of 6.2%.

But if the RW estimate seems mildly optimistic, fasten your seatbelts...

National accounts paint a rosier picture

At the same time the World Bank released the RW estimates, the IMF published an alternative estimate co-authored by Surjit Bhalla, the Indian government's representative at the IMF and a well-published economist who is a veteran of the first ‘Great Indian Poverty Debate’. In their paper, Bhalla and co-authors Karan Bhasin and Arvind Virmani (henceforth BBV) eschew new survey data entirely. Instead, they start from the last official 2011-12 survey and shift the distribution in line with the growth of consumption in the national accounts, and then add in explicit allowance for government food subsidies. They conclude that:

i) India has essentially eliminated extreme poverty. They estimate the proportion of the population below $1.90 in PPP terms at just 0.8% before the pandemic.

ii) The pandemic didn't increase poverty. Rather, according to BBV, "food transfers were instrumental in ensuring that it remained at that low [0.8%] level in pandemic year 2020.”

iii) Inequality has fallen to the lowest level since 1993-94, with a Gini1 (after transfers) of 0.29.

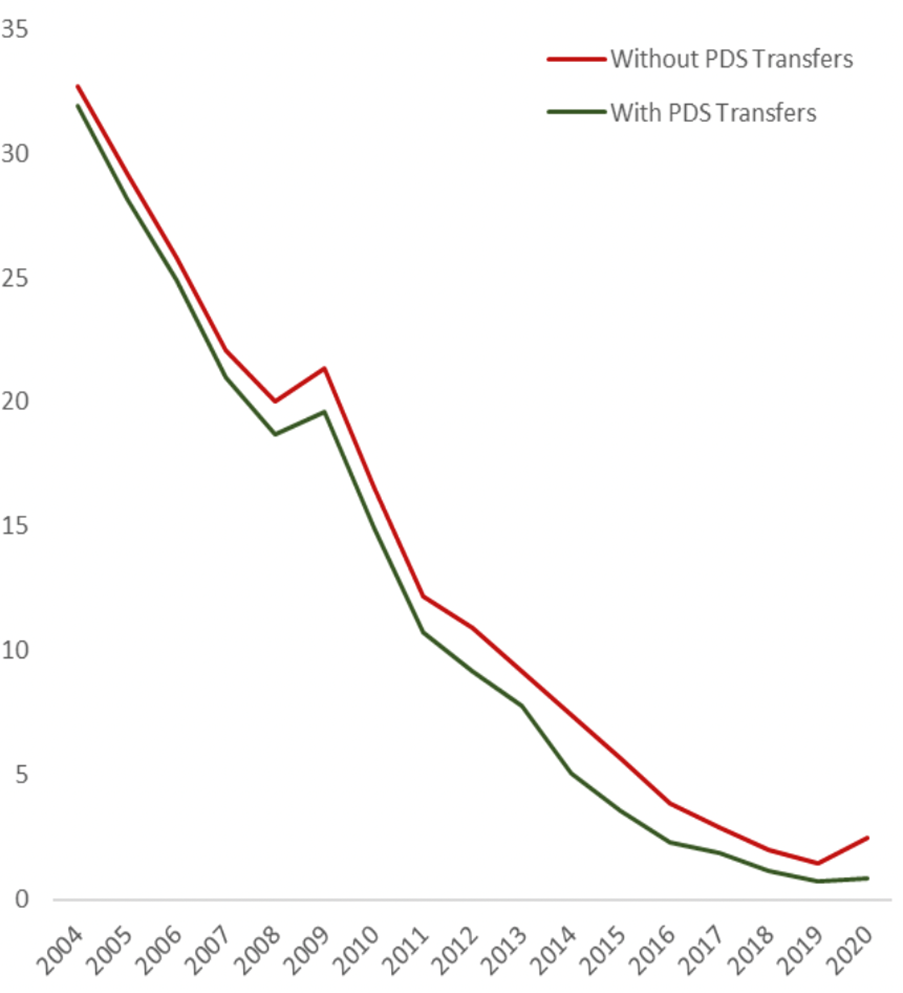

Note that the 0.8% poverty rate that BBV cite here is using a different definition of the underlying consumption aggregate than the one used by the World Bank above (based on the NSS's Modified Mixed Recall Period (MMRP) series instead of the Universal Recall Period (URP) series). In more apples-to-apples terms, their URP number is 1.9% – still very low. The novel and interesting claim in the BBV paper is that previous estimates have overestimated poverty because they rely only on survey measures of actual expenditure on food items, implicitly omitting the government subsidy embodied in India's massive Public Distribution System (PDS).2 Using administrative data on PDS and various assumptions, BBV get a significantly lower poverty rate (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. An alternative view of Indian poverty, with and without adjusting for an increase in transfers from the PDS

Source: Bhalla, Bhasin and Virmani 2022.

Notes: i) Poverty projections use the World Bank’s poverty line of $1.90 PPP per day. ii) The figures on the y-axis indicate the percentage of the population below the poverty line.

It's unclear (to me) how the paper has dealt with leakage from the PDS system, and errors of inclusion and exclusion which we know are rampant. But a recent survey from Gelb et al. (2021) found that the ration system held up quite well during the pandemic. So the question BBV raise about how much Modi's new welfarist policies may have reduced national poverty is an interesting and important one, even if their impact is at most a couple of percentage points.

The deeper challenge with the BBV "zero poverty" calculation is its reliance on official national accounts data, which various pieces of evidence suggest will exaggerate true poverty reduction.

The problem with national accounts

There's been a lot of ink spilled about India's national accounts in the last several years, so it's worth distinguishing two different issues.

First, Arvind Subramanian has made the case that the government began, inadvertently at first but systematically, overstating GDP growth after 2011 (but pre-Modi) (Subramanian 2019a, 2019b). Earlier World Bank estimates for India have included that possibility in their poverty scenarios (Edochie et al. 2022), though neither RW nor BBV do so here. If Subramanian is right, then poverty may be significantly higher than both sets of national accounts projections imply. Indeed, Subramanian’s caution on the recent GDP figures would point in the same direction as RW’s preferred survey-based poverty estimates, at least through 2017.

Second, in the absence of new survey data, BBV extrapolate survey consumption from 2011 by assuming nominal consumption growth in NA passes through to growth in the survey mean, one for one. They show this was roughly true in India’s most recent pre-2011 survey rounds. But a large literature, starting with Ravallion (2003), shows this doesn’t hold in general. More recent World Bank research concludes the most plausible rate of pass-through for India from real consumption in the national accounts to surveys is 0.67 (Edochie et al. 2022). That’s why RW get a much higher poverty rate than BBV, even when the former use the same national accounts data.

To compound matters, the historical national accounts data underlying BBV’s estimates are subject to their own heated debate–totally separate from Subramanian’s critiques of the newer national accounts. In 2018, the National Statistical Commission recommended a backward revision to the GDP series that would have raised the growth rate from 2004-05 to 2011-12 by a fraction of a percentage point. But a few months later, the government’s internal think tank, NITI Aayog, decided to go the opposite direction, and published a new backcast GDP series revised in the opposite direction, implying growth in GDP and consumption before 2011 was more than a full percentage point lower. Critics contended that lowering historical growth helped make the current government look good by comparison. But one side-effect of the downward revision is that it made national accounts and survey data look more consistent, yielding BBV’s finding of 100% pass-through. If instead one stuck with the original pre-2011 national accounts, or even more so the National Statistical Commission’s recommendation, you’d have to conclude 100% pass-through is too high, and hence the implied poverty rate in 2019 is too low.

In sum, there is unlikely to be any resolution to this debate any time soon, but reliance on national accounts data only kicks the ball into even more fraught and politicised territory. As it stands now, we have a wide range of estimates for poverty changes since the last (accepted) estimate of 22.5% for 2011-12: from an increase (according to unreleased NSS data from 2017-18) to a near-elimination by 2019 (according to BBV) with the RW estimate for 2019 falling in-between, at about 10%.

Until the integrity of the official household surveys is restored, any judgment on the Modi government’s efforts to reduce poverty appears tentative at best, and the great Indian poverty debate will go on.

The author would like to thank Surjit Bhalla, Alan Gelb, Christoph Lakner, Maria Ana Lugo, Anit Mukherjee, Sutirtha Roy, Arvind Subramanian, and Roy van der Weide for helpful comments and clarifications. Any conclusions (or errors) here are the author’s alone.

A version of this article previously appeared on the Center for Global Development (CGDev) blog.

Notes:

- The Gini coefficient is one of the most frequently used measures of inequality. It varies between 0 and 1, with a value of 0 indicating perfect equality (all households or individuals earning the same amount of income) and a value of 1 indicating perfect inequality (one household or individual earning all of society’s income).

- While interesting, it’s not clear that it’s strictly valid to add in the subsidy value to Indian consumption for calculating globally comparable poverty rates using the World Bank’s $1.90 poverty line, unless one does the same for other countries, who also have various food and energy subsidies.

Further Reading

- Bhalla S, K Bhasin and A Virmani (2022), ‘Pandemic, Poverty, and Inequality: Evidence from India’, International Monetary Fund, IMF Working Paper No. 2022/069.

- Deaton, Angus and Valerie Kozel (2005), “Data and Dogma: The Great Indian Poverty Debate”, The World Bank Research Observer, 20 (2): 177-200.

- Edochie, I, et al. (2022), ‘What do we Know about Poverty in India in 2017/18?’, World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 9931.

- Felman, J, J Sandefur, A Subramanian and J Duggan (2019), ‘Is India’s Consumption Really Falling?’ Center for Global Development, 9 December.

- Gelb, A, et al. (2021), ‘Social Assistance and Information in the Initial Phase of the COVID-19 Crisis: Lessons from a Household Survey in India’, Center for Global Development, Policy Paper 217.

- Ravallion, Martin (2003), “Measuring Aggregate Welfare in Developing Countries: How Well Do National Accounts and Surveys Agree?”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(3): 645-652.

- Roy, SS and R van der Weide (2022), ‘Poverty in India Has Declined over the Last Decade But Not As Much As Previously Thought’, World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper No. 9994.

- Subramanian, A (2019a), ‘India’s GDP Mis-estimation: Likelihood, Magnitudes, Mechanisms, and Implications’, Center for International Development at Harvard University, CID Faculty Working Paper No. 354.

- Subramanian, A (2019b), ‘Validating India's GDP Growth Estimates’, Center for International Development at Harvard University, CID Faculty Working Paper No. 357.

12 October, 2022

12 October, 2022

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.