Why are politicians with criminal records elected to office, despite voters having the option to weed them out? Based on the hypothesis that criminal politicians strategically deliver targeted benefits to voters, this article examines how such politicians spend funds under India’s national employment guarantee programme. It finds that criminal politicians leverage the programme’s wage dimension to build clientelist relationships with their constituents – at the cost of overall efficiency.

The electoral success of criminal politicians is often associated with detrimental effects on economic welfare and democratic functioning (Prakash et al. 2019, Solé-Ollé and Sorribas-Navarro 2018). Yet, such politicians are regularly elected to office in several parts of the world. Why do voters fail to “throw the rascals out”, despite having the option to do so?

The existing literature provides several explanations for this surprising voter behaviour, such as lack of adequate information (Ferraz and Finan 2008), ethnic loyalties (Banerjee and Pande 2007), or vote-buying (Bratton 2008). These theories rely on the assumption that criminality is an undesirable quality – but what if voters are rewarding criminal politicians for their ability to provide them with targeted benefits?

While there is a large body of ethnographic literature linking corruption or criminality with clientelism (Vaishnav 2017), several empirical studies have found that the electoral success of low-quality legislators has large negative economic costs (Chemin 2012, Prakash et al. 2019). I argue that despite the detrimental effects criminal politicians have on long-term growth, they might be more effective in providing certain resources to their constituents. In particular, to gain an electoral advantage, criminal politicians can leverage their reputation and access to wealth to strategically deliver targeted benefits that they can claim credit for and that voters might care more about. By doing so, they can convey a positive signal of competence, and this is why voters might support them.

Study design and setting

To test this theory, I examine the causal effect of electing criminal politicians on India’s largest anti-poverty programme, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA)1, in the state of West Bengal between 2011 and 2020 (Khemka 2024). Using a ‘regression discontinuity design’ (RDD) comparing constituencies where criminal politicians barely won to those where they barely lost, I test if the election of a Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) with a criminal record impacts the delivery of two main outcomes: number of projects completed, and number of days worked annually. This method leverages close elections by comparing similar constituencies, allowing the isolation of the effect of criminality from other confounding factors.

West Bengal provides an ideal setting to test this hypothesis for several reasons. First, crime is deeply woven into the fabric of West Bengal politics. As of the last state assembly elections in 2021, 49% of winning candidates had a criminal history – with a majority of them accused of serious crimes such as rape, kidnapping or murder. This share has risen steadily from 38% in 2016 and 34% in 2011 – far above the national average and the seventh highest among all Indian states.2 Second, there is substantial variation in the delivery of the programme across Indian states. Since, West Bengal is among the better performing states in terms of allotting MNREGA jobs and utilising funds under the scheme, this ensures that the estimates are at the lower bound.

Jobs over infrastructure: A strategic trade-off

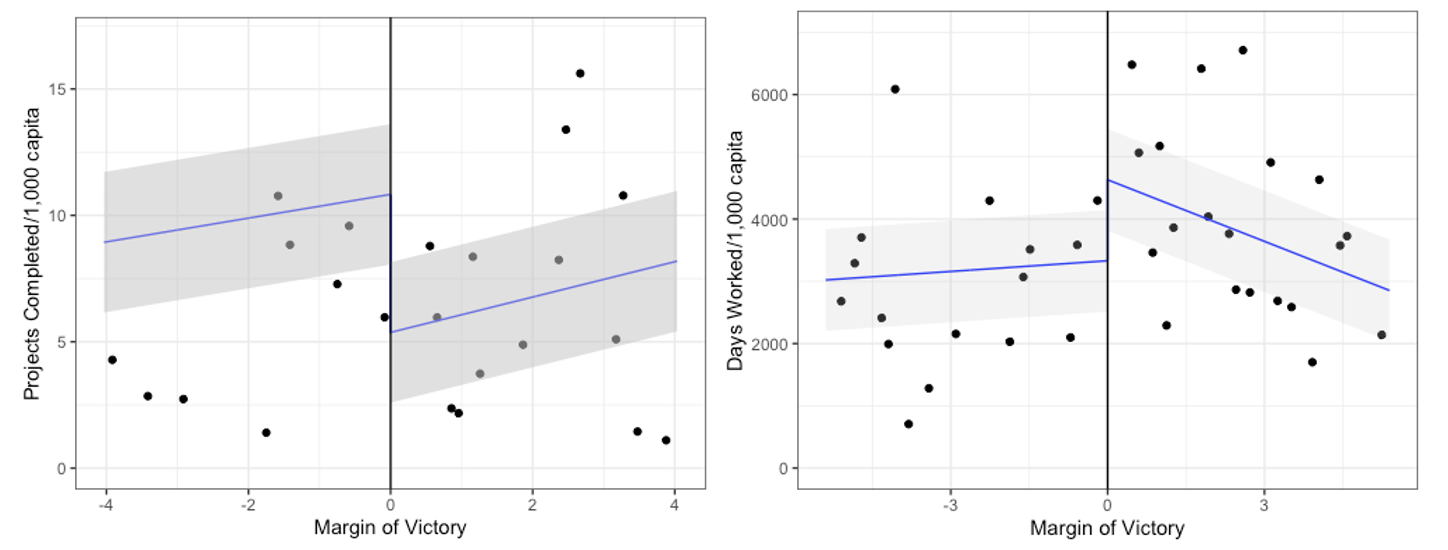

MNREGA serves two goals: in addition to offering guaranteed wage employment at a minimum wage, it also aims to improve village infrastructure such as unpaved roads, ditch irrigation, and canals. My analysis shows that constituencies that elect criminal politicians observe a significant drop in the number of projects completed: On average, while all constituencies initiated a similar number of projects, constituencies where a criminal politician won by a narrow margin complete 5.26 fewer projects per 1,000 residents compared to constituencies where such politicians just about lost (Figure 1). This implies a 68% decrease in project completion relative to the average clean constituency. In contrast, employment under MNREGA increases by 36% in these constituencies, implying a higher wage bill of approximately Rs. 5.21 crores.

I further find this effect is more pronounced for legislators who run for re-elections and contest from non-reserved constituencies. These results seem to suggest that criminal politicians are more inclined to deliver public goods when there are potential electoral benefits on offer.

Figure 1. Effect of electing criminal politicians on number of MNREGA projects (left) and workdays (right)

Notes: (i) The outcome on the left panel measures the number of MNREGA projects completed per 1,000 capita (number of residents), while the outcome on the right panel measures the number of MNREGA workdays per 1,000 capita. (ii) The explanatory variable is the margin of an electoral victory, which measures the difference between the vote share received by a criminal candidate and that of a clean candidate. Positive values indicate the difference between the vote share received by a criminal winner and that of a clean runner-up. Negative values indicate the difference between the vote share received by a clean winner and that of a criminal runner-up. (iii) Since implementation of the programme can suffer from yearly variation and at the village-constituency level, the model includes year-fixed effects, and the standard errors are clustered at the village and constituency level. (iv) The grey shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval, which means that if the experiment were repeated over and over with new samples, the calculated confidence interval would contain the true effect 95% of the time.

Why this distortion?

MNREGA stipulates that 60% of the expenditure must be spent on labour and the remaining 40% on materials. However, due to the lack of proper monitoring, this rule is not always adhered to. I find that constituencies of criminal politicians spend 7.2% more on labour than the stipulated requirement.

To put this in context, the cost of an average project ranges between Rs. 1.5-4.6 lakhs. This means that if these extra funds spent on wages were allocated using the mandated ratio, they could have potentially been used to complete anywhere between 113 and 348 projects annually. Thus, even though criminal politicians generate more employment for their constituents, they seem to reduce overall programme efficiency significantly.

Why do criminal politicians target the wage dimension of the programme? Intuitively, we would think that criminal politicians would concentrate their efforts on the material component since it offers better rent-seeking opportunities. However, several studies have shown that voters have little interest in the material expenditure incurred by public programmes (Olken 2007, Goyal 2024). This is because either they do not hold politicians responsible for corruption in the distribution of common public goods, or they are simply more concerned with their private interest. This lack of voter accountability is especially relevant in the context of MNREGA, which self-selects poor households. Since these households often have more immediate needs, we can construe that they might be more concerned with getting jobs than with the material dimension of the programme. Thus, these findings suggest that criminal politicians strategically target the wage dimension of the programme to build clientelist relationships with their constituents.

Is this corruption? Not quite

A natural concern is whether criminal politicians are simply siphoning off funds. There is sufficient evidence that officials are often complicit in reporting excess wages or overestimating expenses under the scheme (Gulzar and Pasquale 2017, Niehaus and Sukhtankar 2013). However, I find no evidence supporting this argument. Constituencies with criminal politicians do not have any visible difference in average expenditure on wages paid per workday – the overall wage bill is higher on account of more workers being hired under MNREGA. Material expenditure per project is also similar across criminal and clean constituencies3

Policy implications

This study attempts to find a solution to one of the most puzzling problems in politics: why do voters support corrupt or criminal politicians? Contrary to the popular belief that criminality or corruption is an undesired characteristic, my findings reveal that voters might be rationally rewarding such candidates because of their ability to provide them with targeted benefits.

In this respect, the findings bridge the gap between the two competing strands of literature on this issue in India: one that uses qualitative fieldwork to argue that criminal politicians might be more able to “get things done” (Vaishnav 2017), and the other that shows that criminal politicians have adverse effects on overall economic welfare (Prakash et al. 2019). I find that despite the reduction in overall programme efficiency, the election of a criminal politician can have a positive effect on specific policy outcomes. This might explain why voters perceive such politicians to be competent and vote for them on the ballot.

This creates a major challenge for reformers, since the politicians in charge of strengthening State capacity and democratic functioning might have little incentive to do so. Several scholars have noted that in such an environment, the best electoral strategy for criminal politicians is to pursue clientelism by engaging in parochial politics, deepening social divisions, and keeping institutions weak (Vaishnav 2017). In exchange, voters have an incentive to reward criminal politicians because of their ability to sell themselves as being competent. In polities of such kind, curbing the demand for criminal politicians is a long-drawn process, since strengthening State capacity is slow and particularly challenging in the hands of leaders without an incentive to do so.

Notes:

- MNREGA offers a guarantee of 100 days of wage-employment in a year to a rural household whose adult members are willing to do unskilled manual work at the prescribed minimum wage.

- The data on candidates’ criminal records is collected from MyNeta, an open data platform run by the Association for Democratic Reform (ADR).

- One major concern is that the programme often suffers from the existence of ‘ghost workers’ or ‘ghost workdays’. Although there is no straightforward method to measure the existence of ghost workers or days, several indirect measurements show that this is not a potential mechanism driving the results.

Further Reading

- Banerjee, A and R Pande (2007), ‘Parochial Politics: Ethnic Preferences and Politician Corruption’, CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP6381. Available here.

- Bratton, Michael (2008), “Vote buying and violence in Nigerian election campaigns”, Electoral Studies, 27(4): 621-623.

- Chemin, Matthieu (2012), “Welfare Effects of Criminal Politicians: A Discontinuity-Based Approach”, The Journal of Law and Economics, 55(3): 667-690.

- Ferraz, Claudio and Frederico Finan (2008), “Exposing Corrupt Politicians: The Effects of Brazil's Publicly Released Audits on Electoral Outcomes”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2): 703-745.

- Goyal, Tanushree (2024), “Do Citizens Enforce Accountability for Public Goods Provision? Evidence from India’s Rural Roads Program”, The Journal of Politics, 86(1), 97-112.

- Gulzar, Saad and Benjamin J Pasquale (2017), “Politicians, Bureaucrats, and Development: Evidence from India”, American Political Science Review, 111(1): 162-183.

- Niehaus, Paul and Sandip Sukhtankar (2013), “Corruption Dynamics: The Golden Goose Effect”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 5(4): 230-269.

- Olken, Benjamin A (2007), “Monitoring Corruption: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Indonesia”, Journal of Political Economy, 115(2): 200-249.

- Prakash, Nishith, Marc Rockmore and Yogesh Uppal (2019), “Do criminally accused politicians affect economic outcomes? Evidence from India”, Journal of Development Economics, 141: 102370.

- Solé-Ollé, Albert and Pilar Sorribas-Navarro (2018), “Trust no more? On the lasting effects of corruption scandals”, European Journal of Political Economy, 55: 185-203.

- Vaishnav, M (2017), When Crime Pays: Money and Muscle in Indian Politics, Yale University Press.

18 September, 2025

18 September, 2025

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.