For poor, agricultural households, health shocks strain limited resources on medical expenses, and result in loss of potential productive days of employment. Based on data from rural India, this article shows that an illness episode causes a 7% decline in average monthly wage income of the ill individual. Further, the male household head’s illness leads to the wife increasing her market labour supply by 3.2%, on average.

The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has led to one realisation – we do not know enough about how vulnerable households cope with health shocks. For poor, agricultural households in rural areas, health shocks are costly because they not only strain limited household resources on medical expenses but also result in a loss of potential productive days of employment and earnings of the ill members. For such households, even short-term and transitory health shocks may be consequential in the sense that they may have to resort to dissaving, liquidating productive assets, or worse, pulling children out of schools and sending them to work (Heltberg and Lund 2009, Yilma et al. 2014). In new research (Dureja and Negi 2021), we first quantify the income loss due to health shocks, and then identify the within household risk-sharing mechanisms in the form of intra-household labour supply responses of the non-ill members.

Data and methods

We use data from the ICRISAT-VDSA (International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics-Village Dynamics in South Asia) monthly household panel1 survey, which covers around 1,400 households in 30 villages across eight states of India (ICAR (Indian Council for Agricultural Research)-ICRISAT, 2010). We use recent rounds of the survey covering five years from 2010-11 to 2014-15. The employment module of the survey records the number of days in a given month an individual works in the wage labour market, on their own farm, in domestic chores, and in taking care of livestock. Further, within the same module, individuals are asked to report the number of days they were ill in a given month. This information allows us to construct an individual-level monthly panel that tracks the market labour supply and non-market home-production activities, along with illness episodes of each member of the household. For our analysis, we restrict the sample to individuals within the age group of 15-65 years2.

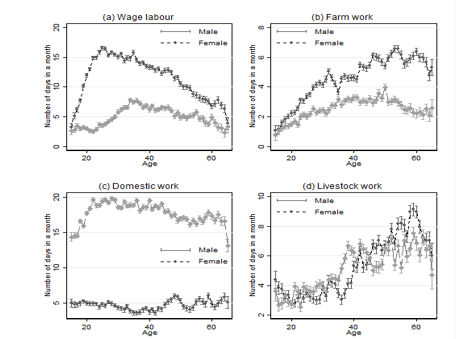

Most individuals in our sample are employed in the informal sector and work primarily as farm workers or in low- or semi-skilled jobs. Figure 1 presents the age-gender division of labour for these rural agricultural households where both female and male members specialise in activities based on their comparative advantages and the opportunity cost of time. Younger men spend more work-days in the wage labour market whereas older men spend more days working on their own farm or taking care of livestock. Women, on the other hand, are primarily involved in domestic chores. Both men and women spend an equal amount of time taking care of livestock.

Figure 1. Age-gender division of labour

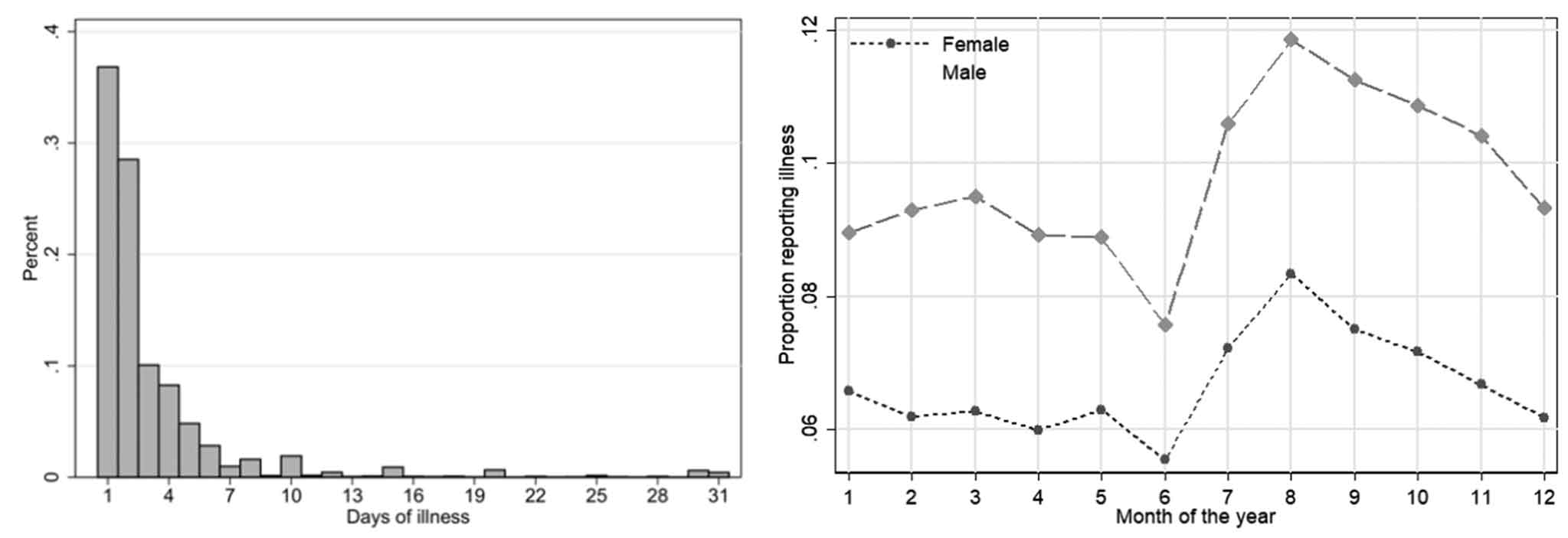

Out of the total individual-month observations, in around 8% of the cases, an individual reports an illness. These self-reported illness episodes are generally short-lived. Figure 2 (left panel) shows the ‘conditional’ distribution of days of illness in our sample of individuals: conditional on the incidence of illness, an individual is ill for just three days in a month, and 92% of the illnesses last for a week or less. The short-term and transitory nature of these illnesses are expected to be unanticipated, and therefore would lead to a temporary change in the labour supply of the household members. To estimate the effect of a health shock, we compare an individual’s labour outcomes within a year, between months of illness and non-illness, while controlling for village-level seasonality3.

Figure 2. Days of illness (left panel) and seasonality in illness shocks (right panel)

Illness, labour supply, and wage earnings

We find that the incidence of an illness shock significantly impacts an individual’s market and non-market labour supply. On average, an illness episode leads to a loss of Rs. 127 in monthly wage income. Given that the average wage earnings in our sample is Rs. 1,777, this loss turns out to be about 7% of the average wage income of the ill individual.

Table 1 shows that illness shocks have implications for labour supply in home production activities as well. Illness shocks reduce individuals’ labour supply in non-market home production activities by about 5.8%, 6.7%, and 7%, of the average work-days spent on own-farm, domestic, and livestock activities, respectively.

Table 1. Impact of illness shocks on individuals’ monthly labour supply

|

|

Market labour supply |

Non-market home production |

|||

|

|

Earnings |

Wage labour |

Own farm |

Domestic |

Livestock |

|

Illness |

-126.853*** |

-0.819*** |

-0.201** |

-0.742*** |

-0.335** |

|

Number of observations |

253,334 |

256,532 |

256,532 |

256,532 |

256,532 |

|

Average |

1,777 |

8.94 |

3.45 |

11.08 |

4.81 |

Notes: (i) The estimates in the table show the difference in an individual’s total monthly wages and works-days when suffering an illness versus months of no illness. (ii) *** denotes that the estimate is highly statistically significant, and implies a smaller standard error and higher precision; *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. (iii) In the data, illness takes the value 1 if illness days is greater than zero.

The gender-based specialisation of labour seen in Figure 1 has a bearing on the impact of illness shocks on wage earnings and labour supply. We find that the loss in market work-days and wage earnings is primarily driven by men as they are the ones who go out and engage in wage employment. The decline in work-days due to illness on own farm is also more pronounced for men as they spend more time in farming activities. However, the decline in work-days spent on domestic chores is more pronounced for women, as household work and domestic chores are largely carried out by women.

We also find that households that do not possess land or livestock may suffer a greater loss in work-days and wage income, because of their greater dependence on market wage employment. Asset-poor households mainly rely on informal wage employment for their livelihood, and hence are more likely to be vulnerable to illness shocks.

Intra-household labour substitution

The decline in the market labour supply of the earning members leads to an aggregate income shock in the household through a reduction in the household’s total monthly wage earnings. We find that an illness shock to the male household head leads to a 4% decline in the total household wage earnings but an illness shock to the household head's wife leads to only a 1% reduction in total household wage earnings.

By reducing the labour supply and earnings of the ill household member, an illness shock changes the opportunity cost of time of the non-ill household members, thereby inducing ‘compensatory’ labour supply responses from them. However, due to gender-based specialisation of labour, discriminatory rural labour markets, and social and cultural norms limiting women’s mobility, the extent to which the forgone work and subsequent earnings of the ill household member can be compensated by other household members may be limited. This is especially true for labour substitution between women and men in the household.

We focus on intra-household labour substitution between the male household head and the wife of the household head. Table 2 shows the impact of an illness shock to the male household head on the wife’s labour supply. In order to smooth out the loss in income due to the household head’s illness, the wife increases her market labour supply by 3.2% (or 0.19 days) in the same month by reducing her work-days in own-farm activities, leading to a rise in her monthly wage earnings by 2.3% (or Rs. 17), on average. This is the ‘added worker effect’4 (Lundberg 1985). However, this increase in earnings is insufficient to entirely offset the decline in household earnings due to the household head’s illness. Women who go out to work primarily work as farm labourers where they are paid significantly less than non-farm activities (Merfeld 2021).

Table 2. Impact of illness shock to household head and the wife on wife’s monthly labour supply

|

|

Market labour supply |

Non-market home production |

|||

|

|

Earnings |

Market labour |

Own-farm |

Domestic |

Livestock |

|

Head ill |

16.743* |

0.187** |

-0.092** |

0.051 |

0.053 |

|

Wife ill |

-66.709*** |

-0.623*** |

-0.144** |

-1.279*** |

-0.388** |

|

Number of observations |

59,243 |

59,402 |

59,402 |

59,402 |

59,402 |

|

Average |

738 |

6.03 |

3.11 |

18.57 |

5.96 |

Notes: (i) A *** denotes that the estimate is highly statistically significant and implies a smaller standard error and higher precision; *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. (ii) In the data, illness takes the value 1 if illness days is greater than zero.

Table 3 shows the added worker effect for the household head when the wife falls ill. The incidence of an illness shock to the wife makes the household head work more on domestic chores and in livestock activities. This added worker effect of the household head is explained by the fact that the wife of the household head spends most of her time in domestic and livestock activities, and therefore, an illness shock to the wife induces the household head to engage more in these activities.

Table 3. Impact of illness shock to household head and the wife on head’s monthly labour supply

|

|

Market labour supply |

Non-market home production |

|||

|

|

Earnings |

Market labour |

Own-farm |

Domestic |

Livestock |

|

Head ill |

-195.302*** |

-1.189*** |

-0.365*** |

-0.379** |

-0.534** |

|

Wife ill |

-1.121 |

-0.108 |

0.032 |

0.109* |

0.102 |

|

Number of observations |

57,923 |

59,402 |

59,402 |

59,402 |

59,402 |

|

Average of the dependent variable |

2,465 |

11.47 |

5.67 |

4.76 |

6.36 |

Notes: (i) *** denotes that the estimate is highly statistically significant and implies a smaller standard error and higher precision; *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. (ii) In the data, illness takes the value 1 if illness days is greater than zero.

While, on average, we find that both the household head and wife respond to each other’s illness by changing their labour supply, several interesting patterns in such compensatory labour supply responses emerge. First, the household head’s increase of domestic work-days in response to the wife’s illness is stronger for households with older household heads. Older men tend to spend more time in own-farm and livestock work than younger men, who spend more time in wage-labour activities. Hence, the opportunity cost of time – in terms of time taken off from market work and substituted into domestic work during wife’s illness – is higher for younger men than for older men5.

Second, younger wives’ labour supply response to husband’s/household head’s illness, is stronger. Wage labour in rural areas requires strong physical work, hence only young women are able to respond to the illness of their husband by increasing market labour supply. Moreover, having more dependents in the households, who can possibly take care of domestic chores, reduces the household head’s added worker effect in domestic chores but increases the wife’s added worker effect in market labour supply. The presence of such dependents leverages the wife’s ability to work outside in case of an illness shock to the household head.

Third, the wife’s labour supply response to the household head’s illness is stronger in asset-poor households, given their limited ability to borrow and wage labour being the only channel to insure against income loss during illnesses.

We also find that the wife’s ability to respond to the household head’s illness is influenced by seasonality in the labour demand cycle. Wives increase their labour supply only in the months of the main agricultural season – when local agricultural work opportunities may be easily available – as opposed to lean agricultural seasons. Hence, labour demand cycles combined with age- and gender-based division of labour, limit intra-household labour substitution as a means to insure against illness-induced income shocks.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that even short-term and transitory illness episodes are consequential for rural agricultural households, implying that a more serious or long-term illness would have much more severe consequences for these households. The impacts of long-term serious illness or disability are harder to identify because they lead to structural changes in the labour composition of the households and induce permanent changes in labour supply. While risk-sharing within the household, through compensatory labour supply responses, does appear to be a means to insure against illness-induced income shocks, this insurance is less than sufficient and is highly sensitive to the demographic composition of the household and the seasonality in rural wage labour markets.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Note:

- Panel data measure the same set of observations (individuals in this case) repeatedly across time.

- An average household comprisese 5-6 adult members: head of the household, the spouse of the head, son(s), daughter(s), and daugther(s)-in-law. For each household, the head (and the spouse of the head) are ‘unique’. However, depending upon the household’s life-cycle, the rest of the composition greatly varies across households. Hence, in our study, we focus on labour substitution between the male head and his wife, but control for the presence of other members in the household.

- Figure 2 (right panel) shows that illness shocks are seasonal in nature as they are more prevalent in monsoon months. Similarly, we observe that labour supply in market and home-production activities also varies across months depending on the village-specific agricultural cycle. This village-level seasonality, if unaccounted, can drive spurious relationship between labour supply and illness.

- A temporary increase in the wife’s labour supply during her husband’s transitory unemployment spell is referred to as the ‘added worker effect’.

- Households with older heads will also correspond to households with more adult members and the household head may not be the primary wage earner in those households.

Further Reading

- Dureja, A and D Negi (2020), ‘Coping with the Consequences of Short-Term Illness Shocks: The Role of Intra-Household Labor Substitution’, IGIDR Working Paper WP-2020-010.

- Heltberg, Rasmus and Niels Lund (2009), “Shocks, coping, and outcomes for Pakistan’s poor: Health risks predominate”, Journal of Development Studies, 45(6): 889-910.

- ICAR-ICRISAT (2010), ‘VDSA survey data documentation’, National Centre for Agricultural Economics and Policy Research.

- Lundberg, Shelly (1985), “The Added Worker Effect”, Journal of Labor Economics, 3(1): 11-37.

- Merfeld, JD (2021), ‘Sectoral Wage Gaps and Gender in Rural India’, IZA Discussion Paper No. 14391

- Yilma, Zelalem, Anagaw Mebratie, Robert Sparrow, Degnet Abebaw, Marleen Dekker, Getnet Alemu and Arjun S Bedi (2014), “Coping with shocks in rural Ethiopia. Journal of Development Studies”, 50(7): 1009-1024.

27 August, 2021

27 August, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.