The declining rates of female labour force participation in developing countries in the last two decades have led researchers to focus on the role of fertility in women’s labour supply decisions. Using a compiled dataset of 103 countries from 1787-2015, this article finds that the effect of fertility is typically zero at low levels of development, and large and negative at higher levels of development.

In her classic monograph, Claudia Goldin (1995) documents that female labour force participation (FLFP) in the US has followed a U-shape over the 20th century, initially decreasing as work shifted from farms and domestic production into factories and formalised workplaces and eventually increasing as women were pulled into the workforce during the Second World War and the post-War period. Canada and Western European countries followed a similar pattern. However, over the last two decades, that post-War trend stopped in some countries, perhaps most notably the US. At the same time, many developing countries, including India have also experienced stagnant or declining rates of FLFP. These latest trends have led researchers to focus on the role of children and, in particular, the increasing cost of childcare for women in the modern economy.

These enduring questions are at the heart of our recent work (Aaronson et al. 2017) which seeks to understand when and why fertility impacts women’s labour supply.

What is the role of fertility in women’s labour supply decisions?

To answer these questions, we assemble a comprehensive dataset on women’s work and fertility, ranging over 200 years and 103 countries. Notwithstanding the breadth of our data, there is a significant conceptual challenge in identifying the effect of fertility on women’s work. Both fertility and labour decisions are made simultaneously, and so common factors affecting both decisions can render the correlation between them uninformative about the key causal and policy effects of interest. We get around this problem by primarily focusing on twin births (following an extensive literature; see Rosenzweig and Wolpin 1980, Bronars and Grogger 1994, Black, Devereux, and Salvanes 2005, and Bhalotra and Clarke 2016). Comparing women who had a singleton versus twin birth, we get something of a natural experiment on the effect of an extra child on a mother’s work. Like all experiments, it is not perfect – it cannot identify the impact of a first child and of course relates to the specific circumstances of a twin birth. We do, however, conduct a host of robustness checks of our analysis, including two other natural experiments that likewise idiosyncratically change the propensity of having an additional child (see Angrist and Evans 1998, and Klemp and Weisdorf 2016), and find similar patterns.

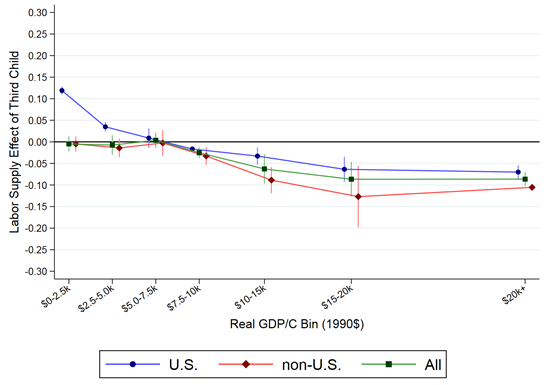

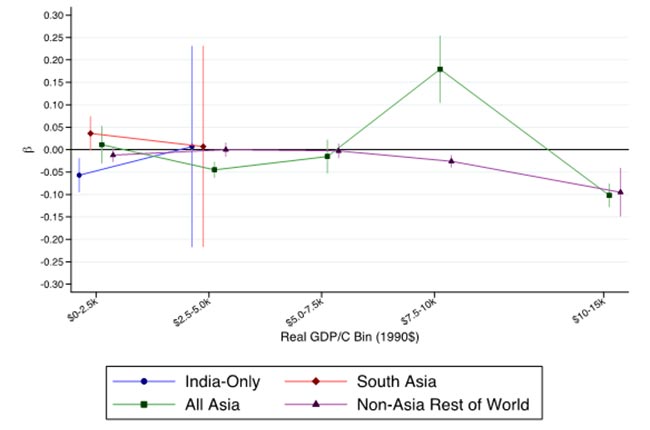

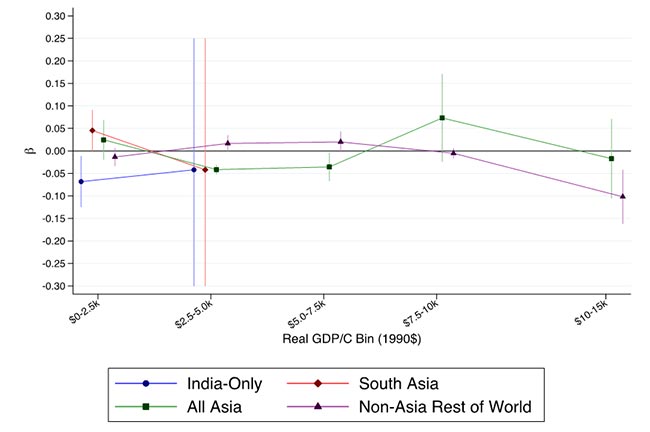

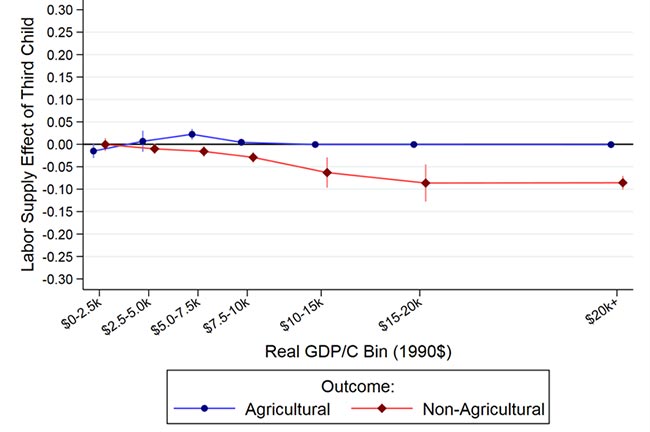

Our results are summarised in Figure 1, where we plot the effect of fertility on mothers’ labour supply (vertical axis) against GDP (gross domestic product) per capita (horizontal axis). At a lower level of income, there is no causal negative relationship between fertility and mother’s labour supply. We see this in early US data, and it also emerges in Figure 2, where we focus on data from Asia, South Asia, and India. In Figure 1, for the early US data, and in Figure 2, for data from Asia and South Asia, we also find some evidence of a positive effect of fertility on labour supply, although notably not in the findings on India.

This result shows up with remarkable consistency across time and space. That is, women in the US or Western Europe pre-Second World War made similar labour supply decisions in response to additional children as women in developing countries today. Moreover, the lack of a negative impact at low levels of development lines up with related studies (Agüero and Marks 2008, 2011) of childless mothers undergoing infertility treatments in a range of developing countries.

Figure 1. Effect of a third child on mothers’work

Notes: This figure shows estimates of the effect of a third child on mothers’ labour force participation using twin births. See Aaronson et al. (2017) for data and methodology details.

Figure 2. Effect of third child on mothers’ work in Asia, South Asia, and India

(a) Rural and urban

(b) Rural only

Notes: This figure shows estimates of the effect of a third child on mother's type of work using twin births. These figures focus on data from Asia, South Asia, and India.

By contrast, at higher levels of GDP, we find a negative effect of fertility on labour supply, consistent with the prior literature based on modern US data and Western European countries (Angrist and Evans 1998, Cristia 2008, and Lundborg, Plug, and Rasmussen 2016). This negative effect is again remarkably robust. Moreover, the impact is economically significant, implying that having an additional child reduces FLFP by roughly 7 to 10.2 percentage points (on a base rate of 67.8%).

Transition of female labour force participation over the development cycle

By combining evidence for both developing and developed countries, including a panel of countries that transition from developing to developed over a long period, we are able to capture the rich transition of FLFP over the development cycle. As countries develop, women’s labour supply becomes more responsive to additional children. Early in the development process, this may entail a shift from a positive, to a nil, to a negative effect of fertility on labour supply.

From both the economic history literature and our contemporary knowledge of developing countries, we know that at low levels of GDP, women work primarily in environments that are often compatible with childcare (example, home production or agriculture). At the same time, given low incomes, households are often at the subsistence margin, and must increase labour supply in order to provide for the additional child. When households escape the subsistence constraint, the fertility effect transitions from positive to nil or (as in the case of India) negative. As incomes increase further, employment shifts into formal and wage work, which is inherently less compatible with childcare, creating a negative link between fertility and FLFP.

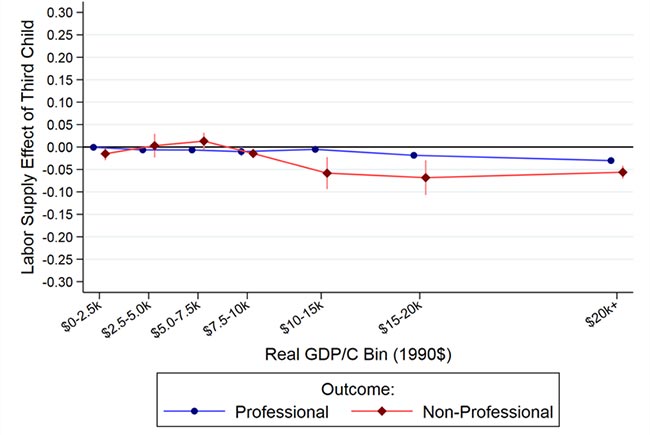

To evaluate this hypothesis, we take a second look at our data in Figure 3, where we examine the effect of children on working in agriculture versus non-agricultural occupations or in professional versus non-professional occupations. The results strikingly support the view that the negative gradient between children and work is very much a feature of non-agricultural work (in which there is a need for childcare, Panel B) and at higher income levels non-professional occupations (in which mothers are less likely to be able to afford childcare, Panel A).

Figure 3. Effect of third child on mothers’ type of work

a) Professional

b) Agricultural

Notes: This figure shows estimates of the effect of a third child on mother's type of work using twin births. Note that rescaling the estimates to account for varying secular rates of labour force participation leads to noisier but similar patterns. See Aaronson et al. (2017) for these details.

Nonetheless, this evidence is indirect, since we cannot attach a specific number to the difference in the cost of childcare between these different work arrangements. There is, however, a growing literature that uses quasi-experimental1 variation in access to childcare or early education to study mother’s labour supply in individual countries, including the US (Cascio 2009, Fitzpatrick 2012, Herbst 2017), Argentina (Berlinski and Galiani 2007), Canada (Baker, Gruber and Milligan 2008), and Norway (Havnes and Mogstad 2011). To take one example, Herbst (2017) analyses the Second World War-era US Lanham Act that provided childcare services to working mothers with young children. In a period when we find the aggregate labour supply response of mothers to additional children was close to 0, Herbst reports that additional Lantham Act childcare funding raised mother’s labour force participation. Summarising this literature, Morrisey (2017) concludes that the availability of childcare and early education generally increases the labour supply of mothers. We view this literature as supportive of the view that the negative effect of fertility on labour supply is amplified if childcare costs increase because jobs become less conducive to child-rearing, and, if so, this dynamic could be stronger among lower wage mothers (example, non-professionals in Figure 3) with less flexibility to provide childcare to young children (Blau and Winkler 2017).

In discussing the evolution of FLFP in the US, Goldin (1990) notes that “…women on farms and in cities were active participants … [in labour] when the home and workplace were unified, and their participation likely declined as the marketplace widened and the specialisation of tasks was enlarged.” In examining the relationship between labour supply and fertility over the process of development and across a wide range of countries, we arrive at a parallel conclusion.

Policy implications

We see three implications of these results. First, our results suggest that the reduction in FLFP at the two ends of the global income distribution can be explained in a unified framework, albeit with different implication for policy. Second, although in developing countries (and for that matter in the historical data from the US) we sometimes observe a positive effect of fertility on labour supply, in India we already observe a negative effect, which suggests that many households have made the transition out of a subsistence labour supply response to additional children. With the need to work in response to an additional child no longer a binding constraint, increases in FLFP are more likely to respond to shifts in social perceptions of the value and prestige of work. Third, in the US and high-income country context, childcare and the changing nature of women’s work seems to be a central factor in explaining attenuating rates of women labour supply. While these are not yet India’s worries, they do likely lie in our future as women’s work becomes more urban and office-based and when, eventually, childcare costs increase.

Note:

- Quasi-experimental designs allow the researcher studying the impact of a treatment or intervention on a target population to control the assignment to the treatment by using some criterion other than random assignment, for example, an eligibility cut-off point.

Further Reading

- Aaronson, D, R Dehejia, A Jordan, C Pop-Eleches, C Samii and K Schulze (2017), ‘The Effect of Fertility on Mothers’ Labor Supply over the Last Two Centuries’, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 23717.

- Agüero, Jorge and Mindy Marks (2008), “Motherhood and Female Labor Force Participation: Evidence from Infertility Shocks”, American Economic Review, 98(2): 500–504.

- Agüero, Jorge and Mindy Marks (2011), “Motherhood and Female Labor Supply in the Developing World Evidence from Infertility Shocks”, Journal of Human Resources, 46(4): 800–826. Available here.

- Angrist, Joshua and William Evans (1998), “Children and Their Parents’ Labor Supply: Evidence from Exogenous Variation in Family Size”, American Economic Review, 88(3): 450–477.

- Baker, Michael, Jonathan Gruber and Kevin Milligan (2008), “Universal Child-Care, Maternal Labor Supply, and Family Well-Being”, Journal of Political Economy, 116: 709–745.

- Berlinski, Samuel and Sebastian Galiani (2007), “The Effect of a Large Expansion of Pre-Primary School Facilities on Preschool Attendance and Maternal Employment”, Labour Economics, 14(3): 665–680.

- Bhalotra, S and D Clarke (2016), ‘The Twin Instrument’, Working Paper, IZA (Institute of Labor Economics).

- Black, Sandra, Paul Devereux and Kjell Salvanes (2005), “The More the Merrier? The Effect of Family Composition on Children’s Education”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(2): 669-700.

- Blau, F and A Winkler (2017), ‘Women, Work, and Family’, Working Paper No. 23644, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Bronars, Stephen and Jeffrey Grogger (1994), “The Economic Consequences of Unwed Motherhood: Using Twin Births as a Natural Experiment”, American Economic Review, 84(5): 1141-1156.

- Cascio, Elizabeth (2009), “Maternal Labor Supply and the Introduction of Kindergartens into American Public Schools”, Journal of Human Resources, 44: 140–170. Available here.

- Cristia, Julian (2008), “The Effect of a First Child on Female Labor Supply: Evidence from Women Seeking Fertility Services”, Journal of Human Resources, 43(3): 487–510.

- Fitzpatrick, Maria (2012), “Revising our Thinking about the Relationship Between Maternal Labor Supply and Preschool”, Journal of Human Resources, 47: 583–612.

- Goldin, C (1995), ‘The U-Shaped Female Labor Force Function in Economic Development and Economic History’, in TP Schultz (ed.), Investment in Women’s Human Capital and Economic Development, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Goldin, C (1990), Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women, Oxford University Press, New York.

- Havnes, Tarjei and Mogstad, Magne (2011), “Money for Nothing? Universal Child Care and Maternal Employment”, Journal of Public Economics, 95: 1455–1465.

- Herbst, Christ (2017), “Universal Child Care, Maternal Employment, and Children’s Long-Run Outcomes: Evidence from the U.S. Lanham Act of 1940”, Journal of Labor Economics, 35(2): 519-564.

- Klemp, M and J Weisdorf (2016), ‘Fecundity, Fertility and the Formation of Human Capital’, Working Paper, University of Warwick.

- Laughlin, L (2013), ‘Who’s Minding the Kids? Child Care Arrangements: Spring 2011’, Household Economic Studies, U.S. Census Bureau, Report.

- Morrissey, Taryn (2017), “Child Care and Parent Labor Force Participation: a Review of the Research Literature”, Review of Economics of the Household, 15: 1–24.

- Rosenzweig, Mark and Kenneth Wolpin (1980), “Testing the Quantity-Quality Fertility Model: The Use of Twins as a Natural Experiment”, Econometrica, 48(1): 227–240.

03 June, 2019

03 June, 2019

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.