A key element of the economy that needs to function well in order to facilitate India’s strong and sustained recovery from the pandemic is the financial system. In this post, Sengupta and Vardhan discuss a few financial sector reforms to understand what has worked well and what has not and lay out a framework for comprehensively thinking about these reforms.

One of the most critical elements of the economy that urgently needs to function well in order to facilitate India's strong and sustained recovery from the pandemic is the financial system. Its proper and effective functioning is also crucial if we want to achieve a 5 trillion-dollar economy in the future. The financial system plays a vital role in converting savings into investments without which no production and employment – the heart and soul of every modern economy – can possibly take place.

Unfortunately, most parts of the financial system in India do not function smoothly and are not sufficiently robust. While the issue of financial sector reforms has been extensively discussed and debated, we argue that the time has come to change the way we think of financial sector reforms and consequently, the manner in which these reforms are implemented. We first discuss a few reforms to understand what has worked well and what has worked poorly and use these examples as a basis to lay out a framework for comprehensively thinking about financial sector reforms.

Three reforms as examples

One of the most extensive reforms undertaken in the Indian financial system till date have been those in the equity market. These took place in the wake of the broader liberalisation and deregulation reforms that were underway in the 1990s. Some of the big changes that took place are as follows (Shah and Thomas 2001):

- The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) that was created in 1988, acquired legal standing in 1993.

- In November 1994, the National Stock Exchange (NSE), opened for business. This was India’s second stock exchange, the first one being the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE), which existed since the late 19th century. In one year, NSE surpassed the BSE and became India’s largest stock exchange.

- Also in 1994, all exchanges in India switched from floor trading to anonymous electronic trading.

- In 1996, NSE adopted risk management through the clearing corporation. Other exchanges also substantially improved their risk containment mechanisms.

- Also in 1996, dematerialisation of shares took place. Today nearly all equity settlement takes place at the depository.

- In 2000 and 2001, equity derivatives trading started with index derivatives and derivatives on some individual stocks.

As a result of these reforms, the equity market underwent a complete and radical transformation. Today, it is one of the best functioning components of the Indian financial system providing capital to a large number of firms.

In contrast, there have been a series of attempts to reform the banking sector in India over the last several decades, but mostly with poor outcomes. In the post-liberalisation period, in order to break free from the erstwhile landscape dominated by public sector banks (PSBs), new private banks were given licenses and foreign banks were permitted entry. Alongside this, several reform initiatives were implemented based on the Narasimham Committee reports (1991, 1998). These brought about changes in the asset classification and income recognition norms of the banks. Since then, many changes have taken place to improve the performance of banks, particularly the PSBs. The government, in its capacity as owner of the PSBs, has established the Banks Board Bureau to facilitate the process of senior-level appointments at the banks, and more recently has initiated mergers among the PSBs. The RBI (Reserve Bank of India) has issued specialised banking licenses to new categories of banks namely small finance banks and payments banks. Despite these policy actions, the sector continues to be plagued by a plethora of problems, most of which manifest themselves in the form of stressed balance sheets and subdued credit growth. Hence, the banking sector reforms may be considered as an example of reforms that have not worked well.

Our final example of financial sector reforms is the most recent one, in the field of corporate insolvency resolution. The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Act (IBC) was enacted in 2016. It is a landmark law in that for the first time, there is a proposal to create a well-defined, comprehensive framework for resolving insolvencies and bankruptcies in non-financial firms. While it set the foundation of a more efficient bankruptcy resolution process, it also required the creation of new institutions such as resolution professionals, and information utilities. The law also made the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) the adjudicating authority for bankruptcy resolution. This implied that the successful implementation of this major reform was contingent upon the diverse components of the system functioning smoothly. However, soon after implementation, the performance of the IBC started getting adversely impacted by the inadequacies in the NCLT set-up, delays in creating a strong and well-trained cadre of insolvency professionals, and the absence of private information utilities.

This can therefore be considered as an example of a reform that has been partially successful but has not delivered the kind of impact that was expected at the time of enacting the IBC.

Framework for reforms

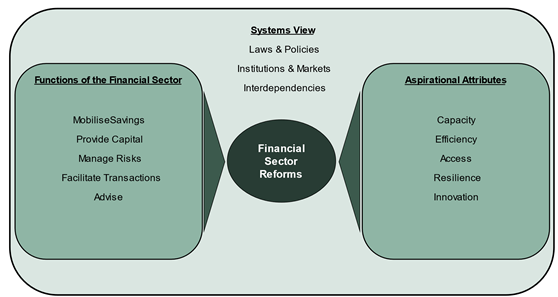

The examples cited above can be better understood using what we call a ‘conceptual map of financial sector reforms’. It looks at three important components of reforms: specific functions of the financial system that the reforms seek to address; aspirational attributes that the reforms aim to develop in the system; and the comprehensive systemic view embedded in the reforms.

Figure 1. Conceptual map of financial sector reforms

Functions

The financial sector performs five main functions: mobilises savings from households and businesses; provides capital in the form of debt and equity to consumers, businesses as well as the government; facilitates transactions including consumer payments, buying and selling of securities, large corporate payments, etc.; manages risks for businesses and consumers through products such as insurance; provides a wide range of advisory services ranging from financial planning and investment advice to individuals, to advising businesses on corporate transactions such as mergers and acquisitions.

When we think about financial sector reforms we must be clear about which of these functions a specific reform aims to improve. Lack of clarity on this is likely to make the reform ineffective. Clarity on the objectives of reforms can also lead to developing targets and metrics that can be used to assess the impact of reforms. Past reforms did not set out clear, objective targets that were to be achieved, nor a mechanism to regularly assess the performance of reform measures.

Attributes

The second important component of any reform is the specific attribute(s) it aims to develop in the financial system. We identify key attributes that we consider ‘aspirational’ for the Indian financial system – capacity, efficiency, resilience, access, and innovation. We believe that any reform must aim to develop one or more of these attributes into any or all of the functions outlined above. We describe each of these attributes briefly below:

- Capacity: It refers to the physical capacity of the financial system to perform its main functions. As an economy grows, the demand on the financial system grows too. Accordingly, the system must build requisite capacity to perform its functions on an ever-growing scale. Else, it can become a drag on the real economy. For example, if the financial system runs out of capacity to provide credit to businesses due to problems in the banking sector or the capital markets, it would stifle the growth of businesses, and have negative consequences on economic growth.

- Efficiency: Capacity must be built keeping in mind the efficiency of the system. All five functions of the financial system must become more efficient as the system evolves. Inefficiencies in any part of the financial system will impose costs on its beneficiaries – individuals, businesses, and the government. The Indian financial system compares poorly with those in the more advanced economies in terms of efficiency. For example, Indian banking has the highest cost of intermediation among all large economies. Given that factor costs – people and information technology – are among the lowest in India, this is intriguing.

- Resilience: Resilience of the financial system is critical. The experience of the last several years demonstrates the need to have a robust banking sector and an overall resilient financial system that can withstand economic cycles. Resilience must be developed at two levels – the system as a whole and for individual entities, at least those that are systemically important. As the real economy becomes large, complex, and globally integrated, so will be the financial system that supports it. Regulatory institutions must adapt themselves to respond to the changing dynamics of a financial system in an evolving economy. Along the way, it will be critical to balance and distribute systemic risk, which is currently excessively concentrated in the banking sector compared to other parts of the financial system.

- Access: The issue of improving access to the financial system has been central to this debate in India for a long time. As the system evolves, it will have to become more equitable and accessible. This means that the financial system will need to extend to unserved and underserved segments for all financial requirements – savings, investments, payments and transactions, risk management, and advisory. These needs must be met for both individuals and small businesses.

- Innovation: Finally, the financial sector must become more sophisticated and advanced through innovation. It could be argued that innovation is not an objective in itself, but a means to achieve the other attributes that have been outlined above (that is, capacity, efficiency, resilience, and access). However, given the dramatic changes that technology is bringing about in the financial system, it can be considered an attribute that reform measures must focus on.

For example, reforms like the launch of Unified Payment Interface (UPI) have altered the consumer payment landscape – it has increased the capacity to process electronic payments, making them more efficient and accessible. At the same time, the use of technology to achieve all of these desirable outcomes also creates new risks (such as information security-related risks, money laundering risks, ransomware attacks, etc) and hence poses new regulatory challenges of effectively containing these risks.

Systemic view

When we think of reforms of the financial system, it is imperative to adopt a holistic approach that takes into account not only what is wrong in a specific part of the financial system but also what other parts of the financial system need to be fixed in order for the reforms to have the desirable outcomes. The discourse on the financial system is often focussed on a particular sector like banking or the bond market, and consequently, the usual narrative is concentrated around narrow sectoral issues. This kind of a narrowly defined view can be problematic because the financial system does not operate in independent silos.

A sound credit system must include a well-run banking system as well as a well-developed bond market. Non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) cannot perform their functions effectively without a strong banking system and a liquid bond market. Large pools of domestic capital such as mutual funds and insurance, cannot be invested unless there are well-functioning securities markets. Securities markets cannot function effectively unless they are regulated well. In other words, savings in the economy get intermediated through multiple different channels – both markets and institutions – that are, by construction, highly interdependent and interconnected. The legal and regulatory foundations of markets and institutions are critical to their functioning, and a reform measure has a higher likelihood of failing if it is not accompanied by necessary changes to the legal and regulatory setup.

Assessing past reforms

We now apply this framework to assess the three reforms we outlined earlier.

The equity market reforms of the 1990s helped improve the first three functions. The market capitalisation of the CMIE (Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy) COSPI (CMIE Overall Share Price Index) increased from Rs. 2.3 trillion in 1990-91 to a whopping Rs. 204.5 trillion in 2020-21. The number of listed companies have gone up from 2,365 to 5,235.

Contrast this with the record of banking reforms. As a percentage of GDP (gross domestic product), bank credit and deposits grew in the 1990s and also in the first decade of the 2010s, but since then the growth has slowed down and in the last few years, it has almost stagnated (Vardhan 2021). Bank credit as a percentage of GDP has remained around 50% for almost a decade now. Repeated phases of high NPAs (non-performing assets) suggest that the sector has not developed resilience to deal with economic cycles. In terms of efficiency gains, the decade of 2000 to 2010 saw some gains, especially in the PSBs, but these gains stalled, and in fact have reversed in the last couple of years (Sengupta and Vardhan 2021).

Continued concerns about financial inclusion expressed by the RBI and other policymakers, and the recent launch of several government schemes such as Jan Dhan Yojana1 and Mudra2, suggest that access to banking has not improved for low-income households and micro and small enterprises.

Recently, the central government has taken steps to merge several weaker PSBs with existing relatively stronger PSBs. It has been claimed that this reform measure will help to strengthen the banking sector that has been struggling with stressed balance sheets for close to a decade. It is not clear which of the functions outlined above will improve as a result of this policy action.

In order to improve the performance of the banking sector, reforms must be targetted not only at fixing the banking firms themselves but also amending the regulatory framework and fixing the loopholes therein – including in the legal foundations of banking and the banking regulator, that is, the RBI. While the government introduced several reforms regarding the functioning of PSBs, the Nationalisation Act of 1969 remains the operative law for them. This, in turn, limits the RBI’s ability to regulate them and create a level playing field along with the non-PSBs. Even the Banking Regulation Act enacted in 1948 has not undergone any comprehensive overhaul. In contrast, the equity markets reforms were accompanied by comprehensive legal and regulatory changes. Arguably, one of the reasons the equity market reforms proved to be successful was because the entire system was transformed as opposed to narrow parts of it.

In other words, while the banking sector has grown organically in size over the last few decades, it is hard to conclude that it has improved meaningfully on any of the aspirational attributes.

On the other hand, with the insolvency reforms, while the legal foundations were properly put in place with the enactment of IBC, 2016 the institutions required to support bankruptcy resolution were not paid attention to, unlike, for example, the equity market reforms where multiple institutions were set up throughout the 1990s in order to facilitate the transformation.

The government has now set up a bad bank (National Asset Reconstruction Company Limited) to help resolve the NPAs of the banking sector and this is considered an important reform. Other than shifting the NPAs to a different balance sheet, it is not clear what new capability has been built into its design. It is like any other asset reconstruction company (ARC) collectively owned by the banks and with a bit of government support (through guarantees) thrown in. It is likely that it would face the same challenges that current ARCs are facing and on account of which these have not been able to make a significant impact on NPA resolution. Moreover, with problems in the IBC set-up, it is not clear which of the attributes will be addressed through this bad bank reform, and in which specific function of the financial system.

The three-question test

In summary, the above discussion leads us to three key questions that must be asked for evaluating any financial sector reform:

- Which function(s) of the financial system will the reform improve?

- What specific attribute(s) of the financial system will the reform seek to develop?

- What other components of the financial system need to be fixed in order to make the reform effective?

Future research should come up with quantitative metrics that can be used for measuring the impact of reforms. A well-defined mechanism to track the performance of these metrics might significantly improve the outcome of reforms. It could also provide a basis to make course corrections along the way.

I4I is on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content

Notes:

- Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana is a financial inclusion programme of the Government of India, which aims to expand access to financial services such as bank accounts, remittances and insurance among Indian citizens.

- Micro Units Development and Refinance Agency Bank (or Mudra Bank) is a public sector financial institution which provides loans at low rates to microfinance institutions and non-banking financial institutions which then provide credit to MSMEs (micro, small, and medium enterprises).

Further Reading

- Sengupta, Rajeswari and Harsh Vardhan (2021), “Productivity growth in Indian banking: Who did the gains accrue to?”, India Review, forthcoming.

- Sengupta, R and H Vardhan, ‘Productivity growth in Indian banking: Who gained?’, Ideas for India, 7 July

-

Shah, A and S Thomas (2001), 'The evolution of the securities markets in India in the 1990s', ICRIER Working Paper 91.

- Vardhan, H (2021), ‘A decade of credit collapse in India’, Ideas for India, 25 June.

15 November, 2021

15 November, 2021

By: Shyamadas Banerji 08 December, 2021

A bit simplistic overview of the financial sector which mixes up the banking system and capital markets . The Indian equity capital market has undoubtedly made progress with more depth. Derivatives are huge with over 6 million contracts. But India's stock exchanges together don't even rank in 12th place in the list of world's stock exchanges. The equity market remains small compared to GDP. Stock ownership is still confined to a small percentage of the population . The bond market has also developed quite well with both private corporate and financial institutional issuers. The banking system is a major problem area with the public sector banks still intermediating the largest share of resources. What is the economic and social rationale for the continuing government ownership of banks? I recall the nationalizing of banks as a mechanism for the then government to ostensibly prevent industrial houses from using banks as in house treasuries. But it was also a grab for financial resources. The evolution of the banking system has not been pretty. It is inefficient and as the article points out with one of the highest intermediation costs and non-performing loans. One cannot but speculate how some crony capitalists continue to obtain loans rom banks . The Kingfisher airline mess and the PNB fraud comes to mind. The government should divest these banks to the private sector after cleaning them up. Let the private sector recapitalize these banks. Foreign banks have not proved to be innovators but a group which likes to concentrate on serving a wealthy layer of society and some corporates. The fintechs are introducing innovations. I was pleasantly surprised by these companies using AI to get around the lack of adequate credit rating or credit scores of individuals. The entire banking regulatory framework needs a fresh look including revising antiquated banking laws. Separating RBI's monetary policy from its bank regulation and supervision functions deserves a considered examination. It might be prudent to set up a separate banking supervision institution . With the increasing number of rural banks and NBFCs , this is a large task which needs adequate resources and specialization. .