Many policies are designed along a particular identity dimension, such as gender or ethnicity. However, such policies overlook the fact that individuals are associated with several identity dimensions at a time. This article demonstrates how the intersection of different identity dimensions may lead to unanticipated effects: political quotas for women in local elections change policies not only in favour of women, but also in favour of low-castes.

A person's identity or sense of self is associated with various social categories, such as gender and ethnicity. A large literature has underlined the role of identity for public goods provision (for example, Alesina et al. 1999), conflicts (for example, Esteban and Ray 2008), policy implementation (Osborne and Slivinski 1996, Levitt 1996, Besley and Coate 1997, Besley and Case 2000, Pande 2003) and other economic outcomes at the individual (for example, Akerlof and Kranton 2000) and geographically aggregated (for example, Easterly and Levine 1997) levels. This literature tends to study one identity dimension at a time (say, ethnicity or gender), while in reality, individuals are associated with several at the same time (say, ethnicity and gender).1 In a recent paper, we demonstrate the importance of the multiplicity of identity dimensions for the design of public policies (Cassan and Vandewalle 2017). To do so, we revisit a well-studied policy – political reservations for women in local elections in India – and show that it impacts policy implementation along the gender identity dimension (as in Chattopadhyay and Duflo 2004), but also alters the distribution of benefits along another dimension, namely, caste. We propose an important variation in gender norms across caste groups as a plausible underlying mechanism.

Political reservations in local elections

In rural India, the lowest official authority is the Gram Panchayat (GP). It is composed of five to 15 contiguous villages, and is led by a president. Since 1993, mandated political representation has been implemented to correct the underrepresentation of two social groups. First, one-third of the president positions are randomly reserved for women. Second, president positions are reserved for low-castes – that is, for Scheduled Tribes, Scheduled Castes, and Other Backward Classes – in proportion to their share in each state. In what follows, we define a high-caste as any Hindu who is not a low-caste.

Reservations for women increase the representation of women and low-castes

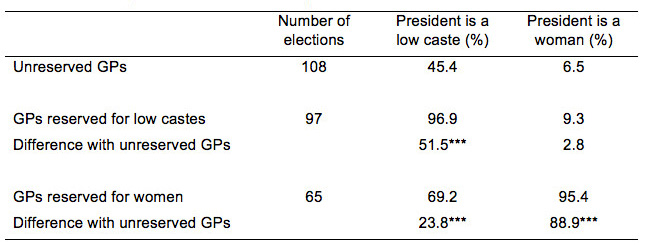

We use the 2005-2006 edition of the Rural Economic and Demographic Survey (REDS), which is representative of rural India, to document that mandated political reservations for women lead to an important change in the representation of women and low-castes. The summary statistics in Table 1 document that gender quota are essential for women to become president – 95.4% of the presidents in GPs reserved for women are female, compared to only 6.5% in unreserved GPs. Similarly, the representation of low-castes more than doubles in the presence of a low-caste quota.

Remarkably, reservations for women do not only change the representation of women, but also of low-castes. The probability the president is a low-caste increases from 45.4% in unreserved GPs to 69.2% in GPs reserved for women.

Table 1. Quotas, gender, and caste of the president

Note: *** Significant at 1%, which means that the probability of wrongly rejecting the hypothesis when it is true is 1%.

Note: *** Significant at 1%, which means that the probability of wrongly rejecting the hypothesis when it is true is 1%. Source: Authors calculations based on the local governance module of the REDS, 2006. village data. Elections reserved both for women and low-castes are excluded from the sample.

Why do reservations for women influence the representation of low-castes? We propose differences in gender norms across caste groups as the underlying mechanism. Indeed, it has been qualitatively documented that high-castes tend to impose stricter restrictions on women’s mobility (for example, Mencher 1988, Drèze and Sen 2002, Joshi et al. 2017). Based on the 2011-2012 edition of the Indian Human Development Survey, we provide quantitative evidence showing that high-caste women are much more restricted in their mobility outside the house – it is less likely they ever worked for pay, they have less say in decisions about their work, have to ask permission to visit places more often, are less likely to be in charge of food shopping, and are less likely to participate in self-help groups. Based on the 2004 round of the National Election Survey, we also show that high-castes tend to see women’s political participation more negatively than low-castes.

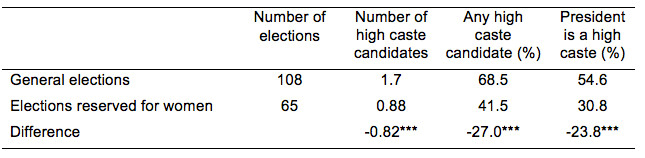

Table 2 shows that these differences in norms translate into a lower political participation of high-castes when there is a reservation for women. As a matter of fact, there is a sharp decline in the number of high-castes running for election and the likelihood that any high-caste will run falls from 69 to 42%. This results in a lower probability the president is a high-caste, and thus a higher probability the president is a low-caste (see Table 1).

Table 2. Gender quotas and high caste political participation

Note: *** Significant at 1%.

Note: *** Significant at 1%.Source: Authors calculations based on the local governance module of the REDS, 2006.

Reservations for women increase policy influence of women and low castes

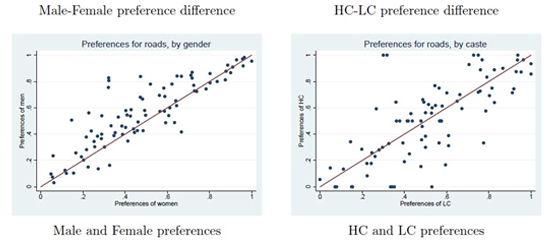

As reservations for women change the political representation along the gender and caste dimensions, it is worth investigating its impact on policy influence. The household survey of the REDS data asks individuals about their preferences for a given list of public goods (water, sanitation, public lighting, communication, roads, and electricity). This allows us to construct an estimate of preference differences between men and women as well as between high-castes and low-castes within a district. Figure 1 graphically represents the preference differences for roads. Each point represents a district in our dataset. The figure suggests there is a large variation in preference differences by gender and by caste across districts and that preference differences for a particular good are not systematically the same across India.

Figure 1. Preferences for roads, by gender and caste

The REDS village questionnaire provides details on the construction and maintenance for the same set of public goods as in the household questionnaire for consecutive elections. This allows us to estimate the alignment of public good provision with the preference difference between men and women, and high- and low-castes. We find that presidents elected in unreserved GPs implement policies that are preferred by men and by high-castes. The bias in favour of men and high-castes is cancelled out when there is a reservation for women. Reservations for low-castes do not alter the advantage of men, but reduce the policy influence of high-castes.

The findings are robust to the use of different measures of preferences, the inclusion of preferences along the class identity (which we proxy by wealth and education), and controlling for the main characteristics of the president.

Conclusions

Women elected under gender quota provide public goods that are closer to the preferences of women and to the preferences of low-castes. We propose an important variation in gender norms across caste groups as a plausible underlying mechanism. High-castes impose stricter restrictions on women’s mobility than low-castes, which translate into a lower political participation of high-castes when there is a reservation for women.

Our paper provides evidence on the importance of taking into account the multiplicity of identity dimensions in the design of public policies. The results suggest that policy design needs to carefully consider the different salient identity dimensions and the potential heterogeneity in the social norms they entail.

The article first appeared in VoxEU: https://voxeu.org/article/identities-and-unintended-effects-public-policies

Notes:

- Other social sciences embraced the multiplicity of identity dimensions earlier. See for example the pioneering work of Crenshaw (1989), who introduced the concept of ‘intersectionality’.

Further Reading

- Akerlof, George A and Rachel E Kranton (2000), “Economics and identity”, Quarterly Journal of Economics,115(3): 715-753. Available here.

- Alesina, Alberto, Reza Baqir and William Easterly (1999), “Public goods and ethnic divisions”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(4): 1243-1284.

- Besley, Timothy and Anne Case (2000), “Unnatural experiments? Estimating the incidence of endogenous policies”, Economic Journal, 110(467): F672-F694.

- Besley, Timothy and Stephen Coate (1997), “An economic model of representative democracy”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(1): 85-114.

- Cassan, G and L Vandewalle (2017), ’Identities and public policies: Unintended effects of political reservations for women in India’, Working Paper No. HEIDWP18-2017.

- Chattopadhyay, Raghabendra and Esther Duflo (2004), “Women as policy makers: Evidence from a randomized policy experiment in India”, Econometrica,72(5): 1409-1443.

- Crenshaw, Kimberle (1989), “Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics”, University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1).

- Drèze, J and A Sen (2002), India: Development and Participation, Oxford University Press, second edition.

- Easterly, William and Ross Levine (1997), “Africa's growth tragedy: Policies and ethnic divisions”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4): 1203-1250.

- Esteban, Joan and Debraj Ray (2008), “Polarization, fractionalization and conflict”, Journal of Peace Research, 45(2).

- Joshi, S, N Kochhar and V Rao (2017), ’Are caste categories misleading? The relationship between gender and jati in three Indian states’, WIDER Working Paper 2017/132.

- Levitt, Steven D (1996), “How do senators vote? Disentangling the role of voter preferences, party affiliation, and senator ideology”, American Economic Review, 86(3): 425-441. Available here.

- Mencher, J P (1988), ’Women's work and poverty: Women's contribution to household maintenance in South India’, D Dwyer and J Bruce (eds.), A Home Divided: Women and Income in the Third World, Stanford University Press.

- Osborne, Martin J and Al Slivinski (1996), “A model of political competition with citizen-candidates”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111(1): 65-96. Available here.

- Pande, Rohini (2003), “Can

mandated political representation increase policy influence for disadvantaged minorities? Theory and evidence from India”, American Economic Review, 93(4): 1132-1151.

19 September, 2018

19 September, 2018

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.