Between 2014 and 2017, seven Indian states amended their regulations to allow women to work night shifts in factories, with the condition that employers provide female-friendly amenities. This article finds that the removal of gender-discriminatory employment restrictions led to an increase in female employment, without negatively affecting male employment. However, the benefits were concentrated almost entirely among large firms.

Do laws designedto protect women from unsafe working conditions constrain the demand for theirlabour? This question sits at the centre of global debates about protectivelegislation in labour markets. Our recent research (Gupta et al.2025) examines what happened when Indian states lifted long-standing bansthat prevented women from working night shifts in factories. Our findings offerimportant lessons for policymakers seeking to expand female employment,particularly considering the significant labourreforms that have been recently initiated by many state governments.

The problem: When protection becomes restriction

For decades,Indian law prohibited women from working night shifts in manufacturing,ostensibly to protect them from unsafe working conditions and exploitation. TheFactories Act of 1948 restricted women to working only between 6 AM and 7 PM inmanufacturing units. Similar laws prohibited women from working night shifts inshops and other commercial establishments. While these laws were intended tosafeguard women's welfare, they inadvertently created barriers to femaleparticipation in the formal manufacturing sector.

This"paternalistic discrimination" (Buchmannet al. 2023) reflects a global pattern. At least 20 countries stillprohibit women from working at night, while 45 countries ban women from sectorsdeemed "unsafe" by lawmakers (World Bank, 2024). Theserestrictions, however well-intentioned, assume women lack agency to make theirown employment choices and that employers are unable to provide safe workplacesfor all workers.

India'sexperience is particularly important given its strikingly low female labourforce participation rates and the potential for manufacturing to provide formalemployment opportunities for women.

The reform: A natural experiment

In the early2000s, a series of High Court judgements held that prohibitions against womenworking at night were unconstitutional because they deprived women of economicopportunities. Following these judgements, between 2014 and 2017, seven Indianstates – Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Maharashtra, Punjab,and Uttar Pradesh – amended their regulations, either through legislativeamendments to existing laws or through executive regulatory orders, to allowwomen to work night shifts in factories, though with certain conditions. Stategovernments typically required employers to provide female-friendly amenitiessuch as separate toilets, transportation facilities, mechanisms to preventsexual harassment, and adequate rest periods between shifts.

These staggeredreforms across states offer a unique opportunity to study the impacts ofremoving gender-discriminatory employment restrictions. We analyse data fromover 290,000 registered manufacturing establishments from the Annual Survey ofIndustries (ASI), in the period from 2009 to 2018, to understand how liftingthese bans affects female employment. We compare changes in firms before andafter the reform and use ‘dynamic estimators’ that allow for the impact of theregulatory change to vary over time. We also use ‘synthetic control estimators’that allow for the construction of a sample of appropriate counterfactualfirms.

Key findings: Size matters

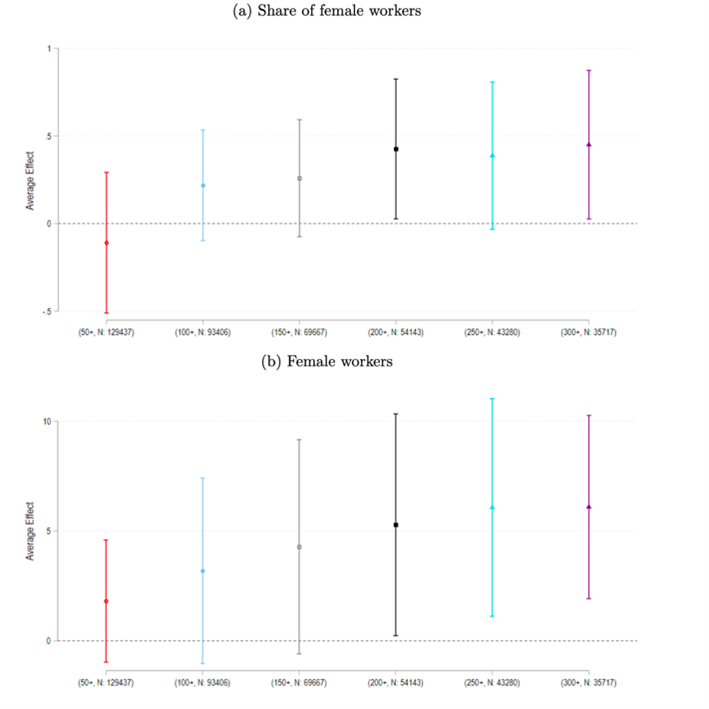

We find thatremoving night shift restrictions increased female employment – but the benefitswere concentrated almost entirely among large firms with 250 or more employees(Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effectsof the reform at firms of different sizes

In states thatlifted the ban, there was a 3.5% increase in the share of female workers atlarge firms, a 13% increase in the number of female workers, and a 6.5% increasein the likelihood of a firm employing any female worker.

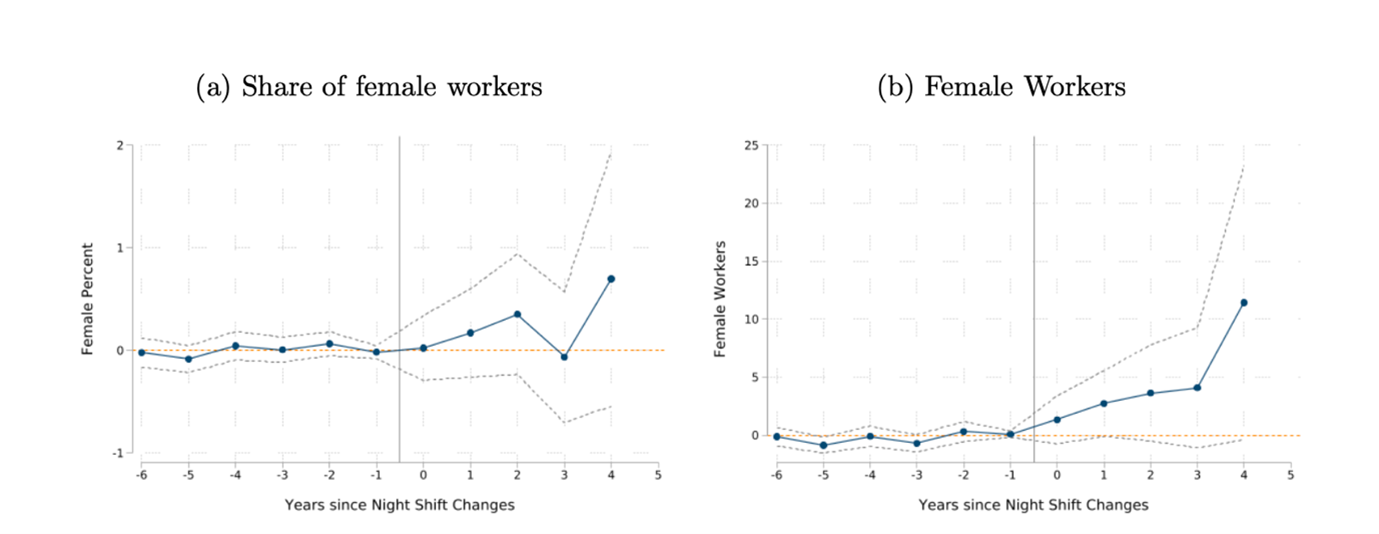

Our results arerobust to the use of synthetic control estimators that construct a comparablecounterfactual group to compare with treated (subjected to intervention) firms(Figure 2). There is no evidence of any trends prior to the reform that couldbe driving our results. After the reform is introduced, both the share offemale workers and the number of female workers steadily increase at largefirms. The gradual increase in the effects of the reform over time couldreflect the time taken by firms to put in place the infrastructure required toemploy women at night.

Crucially, theincrease in female employment did not come at the expense of male workers. Wedo not find any decline in the number of male workers hired at large firms. Infact, we find an increase in the total workforce at large firms, although theestimated coefficient is not significantly different from 0. In short, large firmsmay have expanded their total workforce rather than substituting women for men,suggesting the reforms helped firms overcome labour constraints.

Figure 2. Eventstudy of the impact of the lifting of night shifts (synthetic controlestimator)

Notes: (i) These figures show the dynamic impact ofstate-level amendments that allowed women to work in night shifts in the stateon firm outcomes using the Synthetic Difference-in-Differences (SDID) estimatorby Arkhangelsky et al. (2021). (ii) The regulatory change was made inthe year 0. For control states (not subjected to the reform), the pre-treatmentperiod is before 2014, when the first regulatory change is implemented. (iii) Thesample comprises large firms, which are firms that employ at least 250employees. (iv) All specifications include industry-year and firm level fixedeffects. (v) The bars show the 95% confidence interval for the estimates.

Theconcentration of benefits among large firms reflects the economics ofcompliance with the new regulations. While states lifted the outright ban, theysimultaneously imposed requirements for female-friendly infrastructure andamenities. These compliance costs created a significant barrier for smallerfirms.

Large firms arebetter positioned to absorb these fixed costs for several reasons: they canspread infrastructure investments across more workers, reducing per-workercosts, and they are more likely to already operate night shifts and employ somewomen (Chakraborty and Mahajan 2023).

Who responds most: Export-oriented and firmspreviously hiring females

We furtherexamine which types of firms were most responsive to these regulatory changes. Firmsthat already employed women were much more likely to expand female hiringafter the ban was lifted. This suggests that having existing female-friendlyinfrastructure and experience managing gender-diverse workforces positionedfirms to take advantage of the new flexibility.

Export-orientedfirms showed stronger responses than those focused on domestic markets.Companies operating in competitive global markets appear more willing to hirethe best available workers regardless of gender, making them more responsive tothe removal of hiring constraints. Firms in high-unemployment areas werealso more likely to increase female hiring, likely because they could expandtheir workforce without driving up wages significantly.

Broader economic effects

Despite theincreases in female employment, we find no significant changes in firm outputor profits in the short term. This reflects the relatively small share of womenin the overall manufacturing workforce. Even if firms want to hire women onnight shifts to ease constraints in recruiting a sufficient number ofproductive workers, increases in female employment do not immediately translateto measurable productivity gains at the firm level. We also find a slightreduction in capital expenditure by firms: if labour was substituted forcapital, then this could explain our finding that total output did not change.However, the extent of substitution is too small for us to find significanteffects on profits, at least over the timeframe we are considering.

Wage rates forboth women and men also remained largely unchanged. In some specifications,female wages even decreased slightly, suggesting that the regulatory changesmay have also led to an increase in female labour supply. These results arealso consistent with our previous result that the biggest increases inemployment for female labour took place in labour markets which previous hadrelatively high levels of female unemployment.

Policy implications: Beyond simple deregulation

Our findingscarry important lessons for policymakers seeking to expand female employment. Inparticular, while removing discriminatory laws does help increase femaleemployment, the details of implementation matters. The concentration ofbenefits among large firms suggests that smaller firms need targeted support todevelop female-friendly workplace infrastructure – whether through subsidies,shared facilities, or relaxing some of the compliance requirements where theymay be unnecessarily onerous. Policymakers should also build on existingprogress: since firms that already employ women are most likely to expandfemale hiring, policies encouraging even minimal initial female employment mayhave cascading effects.

The experienceof these seven Indian states offers a glimpse of the economic costs of genderdiscrimination – even discrimination that is arguably well-meaning inintention. Our research provides an example of one such discriminatorylegislation that constrains firms from hiring females who are able and willingto take on productive work and suggests that removing such distortionaryregulation could reduce the economic gap between less developed and more developedcountries.

Further Reading

Arkhangelsky, Dmitry, Susan Athey, David A Hirshberg,Guido Imbens, and Stefan Wager (2021), “Synthetic Difference-in-Differences”, AmericanEconomic Review, 111(12): 4088-4118.

Buchmann, N, C Meyer and CD Sullivan (2023),‘Paternalisticdiscrimination’, Working Paper. A summary of this research is availableon I4I.

Chakraborty, P and K Mahajan (2023), ‘Scaling Up toDecrease the Divide: Firm Size and Female Employment’, Ashoka University EconomicsDiscussion Paper 103.

Gupta, B, K Mahajan, A Sharma and D Walia (2025),‘From Dusk TillDawn: The Impact of Lifting Night Shift Bans on Female Employment’, AshokaUniversity Economics Discussion Paper 147.

World Bank (2024), ‘Women, Business and the Law’.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

%201.svg)

.svg)

.svg)