In the fourth article in the Ideas@IPF2023 series, Seema Jayachandran presents key information about son preference and how it manifests as gaps in health and updates these outcomes with NFHS-5 data. She substantiates a more novel assertion on how elder sons are favoured and its consequences for other children, especially considering and the impact of declining fertility on sex-selection practices. She concludes with a discussion of the shortcomings of commonly employed policies intended to improve the sex ratio in India.

Evidence from India shows that gender gaps in child health have narrowed in recent years. Nonetheless, girls remain disadvantaged in important ways. In addition to gender gaps, there are also stark health gaps between eldest sons, whom parents favor, and other sons. The desire to have a son – to play that eldest son role in the family – drives the skewed sex ratio, and it shows little sign of abating.

In this article I summarise key facts and recent evidence on son preference in India and discuss some policy options. Since a key dimension of son bias is providing more inputs – such as healthcare or education – to sons than daughters, I focus on health.

Gender gaps in health

i) Gender gaps in child health inputs and outcomes have narrowed in recent years

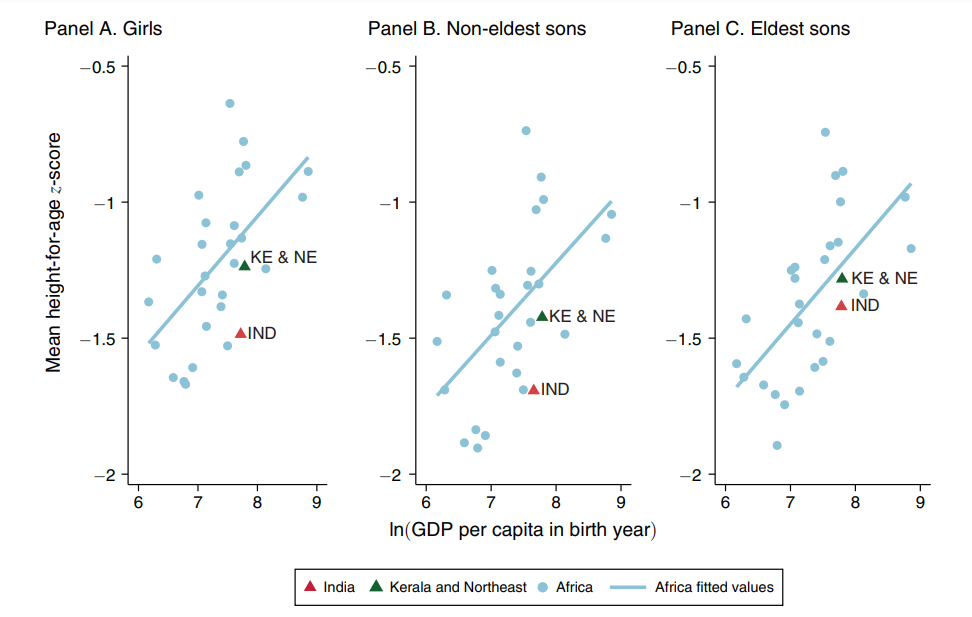

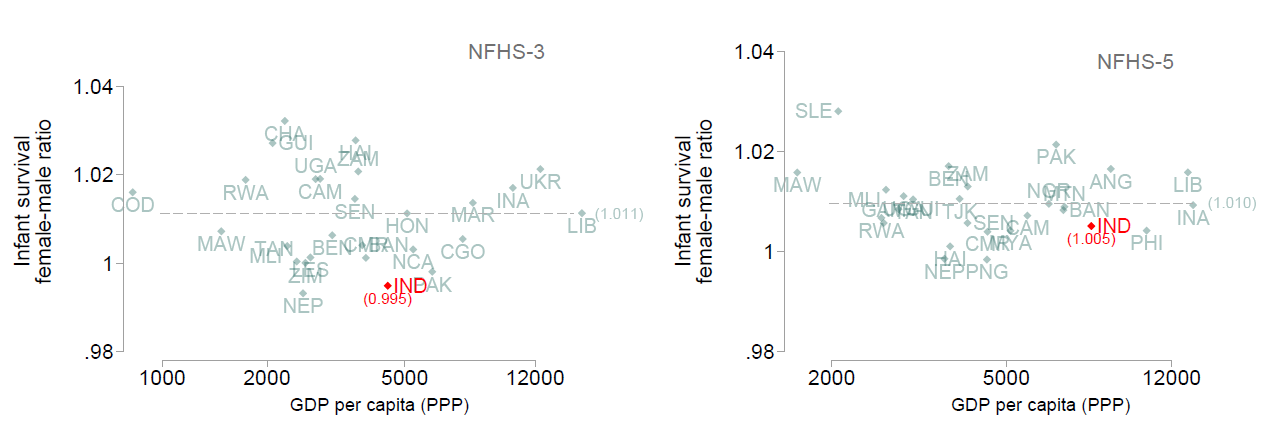

Analysis of India’s National Family Health Survey (NFHS) demonstrates this trend. For example, the female-male ratio in vaccinations has risen over the past thirty years. Similarly, excess infant mortality among females in India has declined in recent years. For infant mortality, it is useful to benchmark India against other countries, because male infants are more fragile, and so parity does not correspond to lack of discrimination. I compare India to other countries1 with Demographic and Health Surveys collected around the same time as the relevant NFHS wave. For comparison countries, the female-male infant survival ratio is 1.01 around both the 2005-06 period when NFHS-3 was fielded, and the 2019-21 period when NFHS-5 was fielded; this appears to be the ‘natural’ rate. In NFHS-3, India’s ratio was 0.99, equivalent to 2 excess deaths per 100 girls born, while NFHS-5 data suggest that India’s deviation from comparison countries has mostly disappeared (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Female-male ratio of infant survival (at the time of NFHS-3 and NFHS-5)

Rising family income, as well as policies and interventions that were not explicitly gendered, might have disproportionately helped girls, because they started out behind. Increased childbirth in health facilities and providing postnatal checkups through home visits might especially help girls, because they would otherwise receive less health care if families have to explicitly make a trip to a health facility for their care.

ii) Nonetheless, girls remain disadvantaged in important ways

Despite these cases of positive trends, several recent studies document that girls continue to fare worse than boys in health inputs such as dietary diversity and seeking healthcare. For example, Dutta et al. (2022) document gender gaps in infant and young child feeding practices using NFHS-4 data, and find that girls under the age of 6 months are less likely to be exclusively breastfed than boys, and then, from age 6 to 23 months, are less likely to be fed high-protein foods. Similarly, Dupas and Jain (2023) analyse claims data from Rajasthan’s Bhamashah Swasthya Bima Yojana Health Scheme (BSBY) health insurance programme that offers enrollees free care in public and private hospitals. They find that girls represent only 33% of hospital visits among children under 10 years.

iii) Unfortunately, making health services free might not be enough to close the remaining gender gaps

Many of the health gaps exist despite health services being free to families, such as in the case of the aforementioned BSBY. Other health inputs without a direct monetary cost, such as breastfeeding and parental time spend on childcare also show gender gaps. How can policy offset parents’ time and hassle costs to obtain health care for their daughters? In the case of medical care, policy options include reimbursement for travel costs. One could offer incentives for care, but while being cautious not to encourage overuse of medical care. An alternative is to reward the outcome: payments for having healthy girls, for example as measured by anthropometrics or anemia levels.

Consequences of desired family composition and eldest son preference

In a 2022 Pew opinion poll, 63% of respondents said that sons should have the primary responsibility for parents’ funeral rites, while only 1% said daughters should and the remaining 35% said responsibility should be shared (Evans et al. 2022). Regarding who bears responsibility for caring for the parents in old age, a majority thought it should be shared between sons and daughters, yet a large minority of respondents – 39% – said that sons bear this responsibility compared to only 2% who said daughters. While the survey questions did not distinguish which son should play this role, Hinduism and patrilocal norms dictate that these are the eldest son’s roles.

Figure 2. Height of Indian relative to African children, disaggregated by girls, non-eldest sons, and eldest sons

Notes: i) The difference between the gap between the Africa fitted line and Kerala and Northeast and the gap between the Africa fitted line and India is 0.231 for girls, 0.235 for non-eldest sons, and 0.098 for eldest sons. ii) GDP data are based on the Penn World Table 9.0 (Feenstra et al. 2015).

Source: Reproduced from Jayachandran and Pande (2017)

i) In addition to gender gaps, there are also stark health gaps between eldest sons – who tend to be most favoured – and other sons

Jayachandran and Pande (2017) reported that the anomalously high rate of stunting in India is almost as stark among non-eldest sons as among girls, but nearly absent among eldest sons. This pattern of eldest sons doing better than non-eldest sons continues to be true in more recent data, and a similar disadvantage for non-eldest sons is also seen for infant survival.

ii) The desire to have a son – to play the role of the eldest son in the family – is what drives the skewed sex ratio.

A well-known pattern of the skewed sex ratio is that it is concentrated on last births in the family, in cases where the previous children are daughters. This pattern is consistent with the premium on having at least one son, which differs from a general aversion to having daughters (for example, because of dowry expenses), which might lead to a high rate of sex selection for first births.

A compelling way to see the link between eldest son preference and sex selection comes from studying patrilocality, the practice whereby a married couple joins the husband’s family and resides near or with his parents. This system creates a strong perceived need to have a son so that he can support and care for his parents in their old age. Ebenstein (2014) shows the strong association between the practice of patrilocality and the male-skewed sex ratio across and within countries.

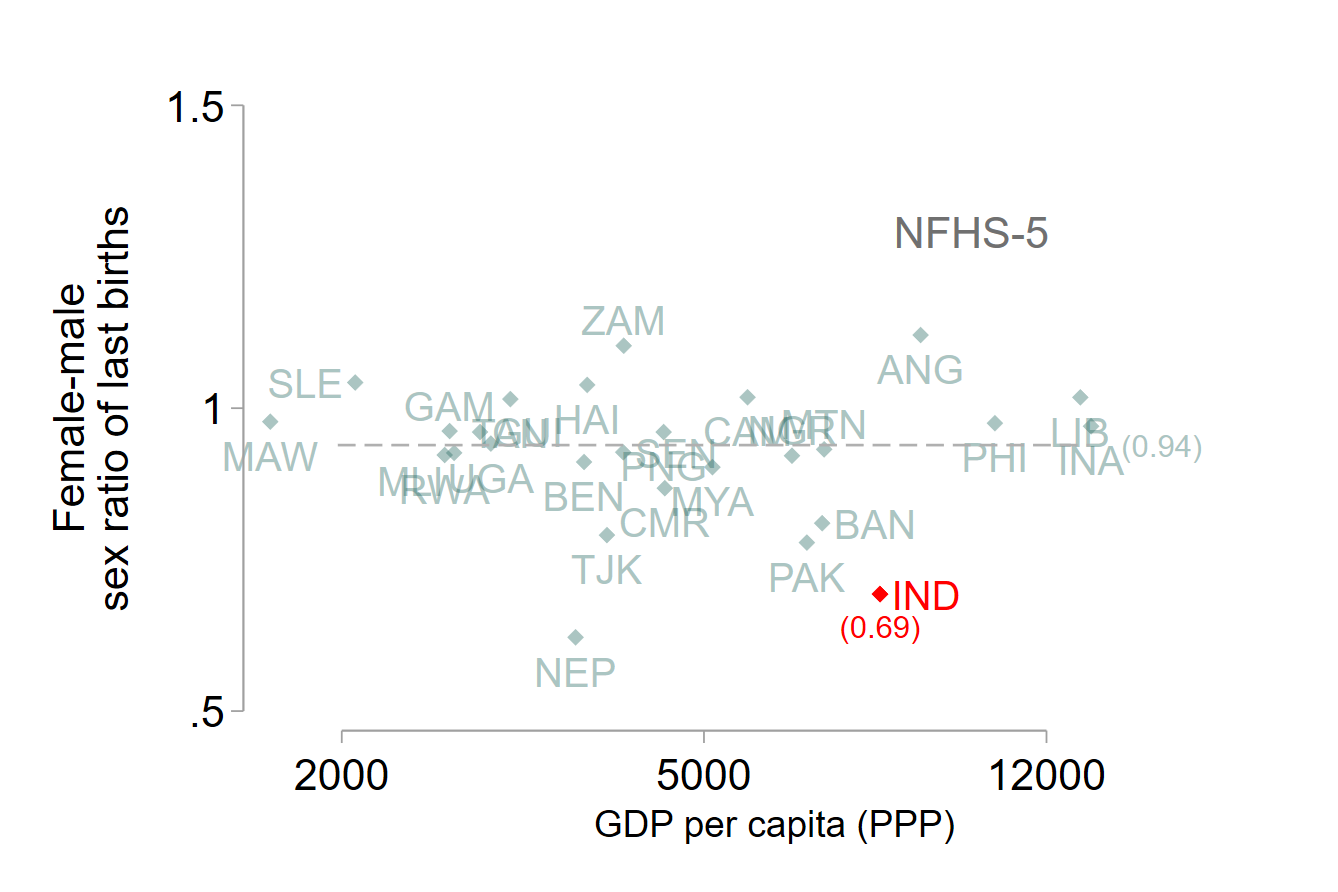

iii) Unlike gender gaps in child investment, the desire to have a son shows little sign of abating

Two measures of the desire for a son are the population sex ratio, which becomes skewed through sex selection or excess mortality of girls, and the sex ratio of the final child in a family, which also incorporates the practice of couples having more children to obtain a son. India is exceptionally low compared to other countries on both metrics, and this pattern has been persistent. Figure 2 shows this metric of the sex ratio of last births in India compared to other countries – India’s ratio is 0.69 girls per boy, while the average among other countries is 0.94.

Figure 3. Female-male sex ratio at last birth (at the time of NFHS-5)

Specifically on sex selection, one possible reason that this pattern has not changed is that sex determination technology has become more widely available and affordable, even with enforcement of the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PC-PNDT) Act, which bans sex selection.

iv) The downward trend in family size is exacerbating how the desire for a son translates into sex selection

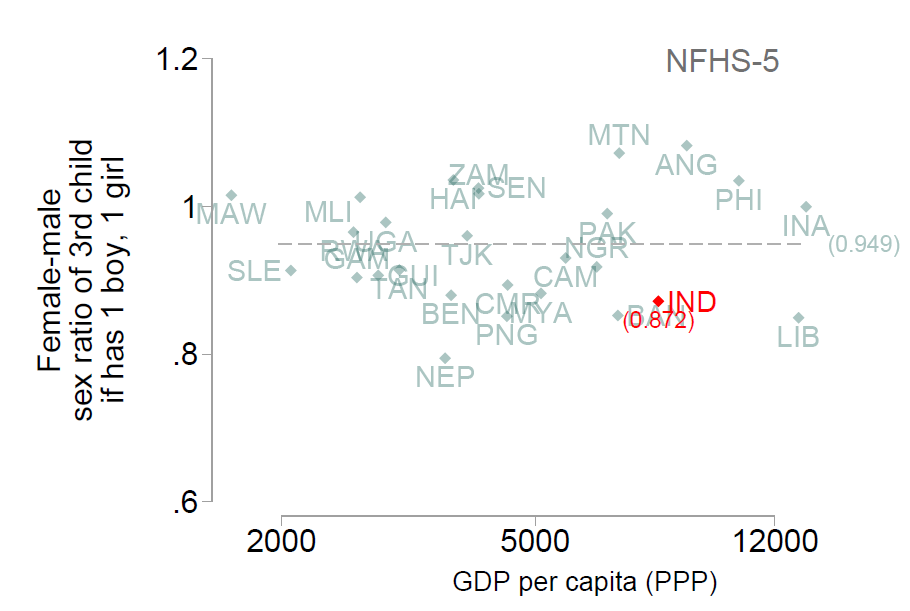

The fertility squeeze is the idea that when family size is smaller, fewer families will have at least one son naturally. When parents want to have three or four children, the likelihood of naturally ending up with no sons is relatively small, but this scenario becomes more likely when couples want to have two or even just one child. Therefore, as fertility rates decline and couples' desired family size gets smaller, they are more likely to resort to sex-selective abortions to obtain their desired son. Jayachandran (2014), using survey data from Haryana, documents this pattern that the desired sex ratio is more male-skewed at low fertility levels. However, the sex ratio for the third child is fairly balanced once the family has a son and achieves the ‘ideal’ family composition of one boy and one girl (Figure 3)

Figure 4: Sex ratio of third child when family has one boy and one girl (NFHS-5)

v) Families’ quest for a son also has collateral damage on his sisters’ health

A by-product of fertility choices around obtaining a son is that girls sometimes receive fewer inputs than boys. One channel for this is through family size – a couple whose first two children are both sons, by chance, is more likely to stop having children than if the first two children are girls. The second couple will keep trying to have a son. This type of fertility behaviour means that girls, on average, grow up in larger families. Given fixed financial resources, girls will be raised in families that have fewer resources to spend on each child. Thus, even if boys and girls receive equal inputs within the family, because of cross-family difference, girls will receive fewer resources.

Another phenomenon, shown by Jayachandran and Kuziemko (2011), is that because women in India want to and are more likely to become pregnant again after a daughter is born, they stop breastfeeding girls sooner to regain their fecundity or because of the new pregnancy. This is detrimental to girls who miss out on the health benefits of breastfeeding. Here, the harm to girls arises even without parents having an explicit preference to provide more health inputs to sons.

Policy implications

i) Empowering women is not a panacea that will solve the problem of son preference

What policies can mitigate son preference? Addressing the skewed sex ratio is especially challenging. The fact that the skewed sex ratio is exacerbated when family size is smaller upends some standard intuitions about policy solutions. For example, educating girls so that they grow up to be empowered mothers might perversely worsen the sex ratio. This is because there are two offsetting effects: although education reduces son preference at any given family size, it also decreases desired family size, and a smaller family size implies a more skewed sex ratio if it remains important to many women to have at least one son (Dreze and Murthi 2001, Pande and Astone 2007).

This is consistent with the findings of Chhibber et al. (2021), who analyse the 2001 and 2011 Census and find that the sex ratio at birth is more skewed among more educated mothers. They also find that the survival rate of girls is higher among educated mothers, but this second force is not enough to offset the first force, and so educated mothers end up with fewer surviving girls.

Therefore, a progressive force like female education does not seem to improve the sex ratio (even if it has other benefits for girls’ outcomes).

ii) Offering financial incentives to have daughters risks further concentrating girls in poorer families

A widely used approach to address the skewed sex ratio in India is to offer financial incentives to have daughters. There are at least three limitations of this approach. First, it can be an expensive solution because most of the payments are inframarginal, or to couples whose behaviour is unchanged by the incentive. Suppose a programme increases the share of newborns who are girls from 45 to 50% – this means that for every 50 girls who were born, 45 of them would have been born even without the incentives. Second, offering payment to have daughters could crowd out the intrinsic valuation of daughters. The third and perhaps, most worrisome limitation of such programmes is that most of the increase in the birth of girls will be in poor families. Many government schemes limit participation to poor households, but even without such a restriction, a given payment level will be more influential for fertility choices for a poor family than a rich one (As in, girls are disproportionately born into larger families and receive fewer resources on average). What policies, then, can work? We do not really know, but there are several policies that warrant pursuing or testing. Enforcement of the PC-PNDT Act that bans sex-selection should continue to be a priority. Other policy options include ramping up delivery of health inputs and health care through schools, public pensions as an alternative to old-age support from sons, and policies that strengthen the intrinsic value that Indian families place on girls.

This is a summary of a preliminary draft paper prepared for the NCAER India Policy Forum 2023.

Note:

- The comparison countries for NFHS-3 are Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Benin, Cambodia, Cameroon, Chad, Colombia, Congo, Congo, Dem Rep, Guinea, Haiti, Honduras, Indonesia, Jordan, Lebanon, Lesotho, Malawi, Mali, Morocco, Nepal, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, Ukraine, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The comparison countries for NFHS-5 are Albania, Angola, Armenia, Bangladesh, Benin, Cambodia, Cameroon, Colombia, Gambia, Guinea, Haiti, Indonesia, Jordan, Lebanon, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Moldova, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia.

Further Reading

- Chhibber, Pradeep, Francesca R Jensenius and Susan L Ostermann (2021), “Missing Girls: Women’s Education and Declining Child Sex Ratios in India”, Economic and Political Weekly, 56(6): 52-60. Abridged for Ideas for India here.

- Drèze, Jean and Mamta Murthi (2001), “Fertility, Education, and Development: Evidence from India”, Population and Development Review, 27(1): 33-63.

- Dupas, P and R Jain (2023), ‘Women Left Behind: Gender Disparities in Utilization of Government Health Insurance in India’, Working Paper. An earlier version is available here.

- Dutta, Swati, Sunil Kumar Mishra and Aasha Kapur Mehta (2022), “Gender Discrimination in Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices in India: Evidence from NFHS-4”, Indian Journal of Human Development, 16(2): 286-304.

- Ebenstein, A (2014), ‘Patrilocality and Missing Women’, SSRN Working Paper.

- Feenstra, Robert C, Robert Inklaar and Marcel P Timmer (2015),"The Next Generation of the Penn World Table", American Economic Review, 105(10): 3150-3182.

- Jayachandran, S (2014), ‘Fertility Decline and Missing Women’, NBER Working Paper 20272.

- Jayachandran, Seema and Ilyana Kuziemko (2011), “Why Do Mothers Breastfeed Girls Less Than Boys? Evidence and Implications for Child Health in India”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(3): 1485-1538.

- Jayachandran, Seema and Rohini Pande (2017), “Why Are Indian Children So Short? The Role of Birth Order and Son Preference”, American Economic Review, 107(9): 2600-2629.

- Pande, Rohini P, and Nan Marie Astone (2007), “Explaining Son Preference in Rural India: The Independent Role of Structural Versus Individual Factors”, Population Research and Policy Review, 26: 1-29.

- Evans, J, N Sahgal, AM Salazar, KJ Starr and M Corichi (2022), ‘How Indians View Gender Roles in Families and Society’, Report, Pew Research Center.

13 July, 2023

13 July, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.