Despite significant improvements in women's educational attainment and reduced fertility rates, India’s female labour force participation (FLFP) remains among the lowest globally. Using nationally representative data for 2004-05–2011-12, this article explores the role of the threat of sexual violence: an additional crime per 1,000 women in a district reduces the expected probability of working by 6.3 percentage points among women of working age.

Two alarming trends have gained much attention in India over the past two decades. First, female labour force participation (FLFP) has remained one of the lowest in the world, despite significant improvements in women's educational attainment and a decline in fertility rates. The International Labour Organization (2019) places India at the 179th position among 185 countries on FLFP. Second, there seems to be an increase in the media coverage of sexual crimes against women – driven either by an increase in reporting or by an actual increase in crimes. In a 2012 survey of adolescent girls in Delhi, 92% reported having experienced some form of sexual violence in public spaces in their lifetime (United Nations (UN)-Women and International Center for Research on Woman (ICRW), 2013).

In new research (Chakraborty and Lohawala 2021), we explore whether – and to what extent – the threat of sexual violence affects FLFP that involves travelling away from home. FLFP can be considered a rational choice wherein she works if the expected benefit from work exceeds the expected cost of work. While all forms of crime that happen outside the house are likely to increase the ‘cost’ of travelling to work, sexual crimes are presumably much costlier for women in a society that attaches a high stigma to victims of such crime. In contrast, while the perceived threat of murder or theft might deter travelling to work, these crimes do not have the additional cost of stigma, and are likely to be uniformly costly across women and men1.

Threat of sexual violence and women’s work: Data and methods

We obtain employment information for the urban sample of women in the working-age group (21-64 years) from four waves of the National Sample Survey (NSS) conducted between 2004-05 and 2011-122, and combine this with police records (National Crime Records Bureau) on district-level incidences of reported sexual crimes, specifically rape, molestation, and sexual harassment. Our focus on the urban sample is driven by the possibility that non-agricultural jobs in the urban regions are more likely to require travelling away from home compared to predominantly agricultural jobs in the rural regions.

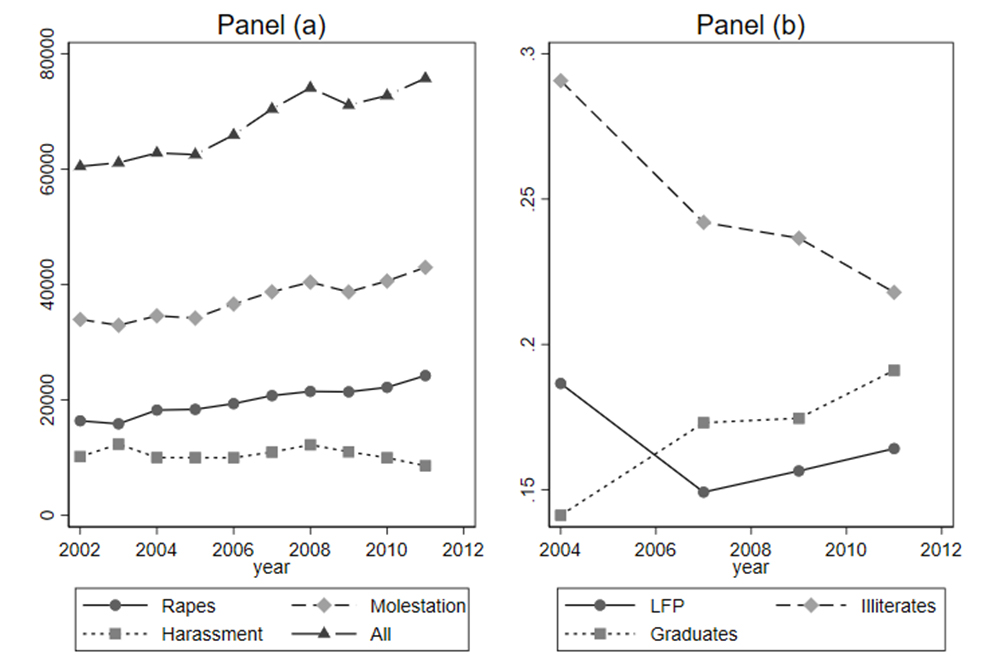

Figure 1 shows the national trends in sexual crimes and FLFP in our sample. Panel (a) shows that rape, molestation, and overall complaints related to sexual offenses steadily increased between 2004 and 2012. Panel (b) shows that FLFP declined over this period. Moreover, the stagnancy in FLFP contrasts sharply with the steady improvement in educational attainment levels. During this period, the percentage of urban women with a graduate degree increased, and the percentage of illiterate women fell. One might argue that this reduction in FLFP could merely be an artefact of the redirection of working-age women to higher education. However, we find that FLFP was declining or stagnant across all age groups and, if anything, moderately increased in the education-seeking age group of 20-30 years. Overall, these trends point towards a worsening, or stagnation at best, of both sexual crimes and FLFP between 2004 and 2011.

Figure 1. National trends in sexual crimes (Panel (a)) and FLFP and education (Panel (b))

Notes: (i) Panel (a) describes the trends in total registered cases of rapes, molestation, and sexual harassment In India during 2002-2011. (ii) Panel (b) shows the trend in percentage of urban women (age group 21-64) employed in workforce, percentage of illiterate women, and percentage of women with at least graduate level education between NSS years 2004 and 2011.

These apparent time-series correlations, are however, far from establishing causality since trends in FLFP, and sexual crimes against women, could both be driven by a third unobserved trend. Poor labour market conditions, for instance, could explain rising levels of male unemployment and consequently, an increase in crimes against women, and simultaneously account for falling levels of FLFP (Caruso 2015).

However, the biggest challenge in estimating a causal relationship is that regions that witness a higher incidence of sexual crimes against women are also the ones where women are less likely to travel for work – not necessarily only because of higher crimes but because these regions could have inherent, time-invariant, differences vis-à-vis regions with low crimes against women. For instance, these regions might be more conservative, less economically developed, and have a higher fraction of unemployed men, etc. On the other hand, regions where women are more likely to work, and hence more exposed to crime, are likely to have higher incidences of sexual crimes against women. As a result, past evidence provides a mixed bag – some find a positive relationship while others find a negative relationship between sexual crimes against women and FLFP (Mukherjee et al. 2001, Chakraborty et al. 2018).

To overcome these concerns, we compare changes over time within the same region, eliminating the possibility that time-invariant covariates of sexual crimes are driving the observed relationship between sexual crimes against women and their LFP rates. Additionally, we account for differences in linear trends across districts and various individual- and household-level covariates.

Key finding

Our most conservative estimates suggest that an additional crime per 1,000 women in a district reduces the expected probability of working by 6.3 percentage points among women in the 21-64 age group. As per the 2011 Census, roughly 50% of India’s 586 million women belong to this working-age category. This implies that for every additional crime per 1,000 women in a district, roughly 32 women are deterred from joining the workforce3.

To the extent that sexual crimes against women add to women’s cost of going to work but not to that of men’s, we would not expect any relationship between sexual crimes against women and men’s employment. We check this possibility through a placebo exercise using the sample of men in the working-age group, and we do not find any effect of sexual crimes against women on men's employment. Further, while sexual crimes seem to dissuade women from working across religions, regions, income, and education levels, this effect is more prominent for women in Muslim households. This gives us the reassurance that the effect of sexual crimes on women’s employment that we observe, is not driven by other labour market trends that may be correlated with both sexual crime against women and employment outcomes. Additionally, we do not find any significant impact of gender-neutral crimes, like theft and murder, on women's decisions to work.

In contrast to the actual crime reports that we have used in our research, Siddique (2021) also estimates this relationship between 2009 and 2011 using the perceived risk of sexual crimes. She measures perceived risk based on the number of media reports of sexual crimes that happened due to political conflict, like riots etc., in a few prominent English dailies as recorded by the GDELT (Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone) data. Given the restriction to political crimes, the vast linguistic diversity of India, and the relatively limited reach of English print media across the wider population, this measure is likely to be a significant underestimate of the actual risk. Even then, she finds a significant negative effect of perceived threat on women's decision to work.

Measurement error is also a concern with police records due to the under-reporting of sexual crimes. Under-reporting could be random across regions, or it could be systematically higher in regions where women are less empowered and, hence, less likely to participate in work4. In both cases, our estimates would be biased downwards.

To address this possibility, we exploit state-level regulations in alcohol sale and consumption and provide estimates from two different strategies. In the first approach, we use the variation in minimum drinking age policies to induce a variation in sexual crimes. Despite the weak law enforcement and non-trivial evasion, legal drinking age policies have been shown to affect the likelihood of consumption and instances of crimes against women in India (Luca et al. 2019). We use this variation in access to alcohol as an ‘instrumental variable5’ for sexual crimes against women. Our second approach relies on the variation in the potential difficulty of obtaining alcohol within Gujarat. Although Gujarat has banned alcohol since the 1960s, the intensity of the ban is likely to vary within the state due to the porous Gujarat border. People in Gujarat, residing in proximity to states without the ban, can buy alcohol more easily outside of Gujarat, than people in districts located further away in Gujarat's interior. We use this variation in the potential difficulty of obtaining alcohol within Gujarat to conduct a contiguous-border analysis. The key idea is that districts of Gujarat close to neighbouring states would be more susceptible to sexual crimes when compared to those in the interior of Gujarat due to variation in access to alcohol. Comparing adjacent districts within Gujarat allows us to minimise the time-invariant as well as time-varying district-level confounders, like unemployment rates, that potentially affect both sexual crimes and women's workforce participation.

Our estimates in both approaches indicate a large deterrent effect of sexual crimes on women's workforce participation than the baseline estimates, suggesting that our baseline estimates might indeed be downward biased due to measurement error.

Conclusion

Our findings underline the importance of accounting for high rates of crimes against women while designing policies to encourage FLFP. Childbearing is considered to be the most critical factor preventing women from participating in the labour force. Accordingly, an overwhelming focus of policymaking in this regard has been on introducing and enforcing maternity and childcare benefits across the world. In India, and many other countries with high rates of crime against women, policies aimed at reducing crimes against women could be equally important to bring down the personal cost to women of participating in the labour force. The economic benefits of such policies, in terms of potential increases in women's labour supply, are an added advantage, over and above the ethical and social imperatives that primarily drive policies to reduce crimes against women. However, reducing crimes against women is a slow-moving process. Examples from across the world suggest that complementary strategies such as ensuring safer means of travelling to work for women, can be successful in the short run (Borker 2020, Kondylis et al. 2020, Aguilar et al. 2021).

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Notes:

- While our study is based in India, the question is generally relevant, in varying degrees, across the world.

- We use data from the 61st, 64th, 66th and 68th NSS rounds for this analysis.

- Our estimates are robust to alternative empirical specifications, estimation samples, and variable definitions.

- The latter creates an ‘endogeneity’ issue in that women’s empowerment is correlated with reported sexual crimes (explanatory factor), and also with FLFP (outcome of interest), making it difficult to establish that reported sexual crimes are causing lower FLFP

- Instrumental variables are used in empirical analysis to address endogeneity concerns. An instrument is an additional factor that allows us to see the true causal relationship between the explanatory factor and the outcome of interest. It is correlated with the explanatory factor but does not directly affect the outcome of interest.

Further Reading

- Aguilar, Arturo, Emilio Gutiérrez and Paula Soto Villagrán (2021), “Benefits and Unintended Consequences of Gender Segregation in Public Transportation: Evidence from Mexico City’s Subway System”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 69(4).

- Borker, G (2020), ‘Safety First: Perceived Risk of Street Harassment and Educational Choices of Women’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 9731.

- Caruso, R (2015), ‘What is the Relationship between Unemployment and Rape? Evidence from a Panel of European Regions’, Working Paper.

- Chakraborty, Tanika, Anirban Mukherjee, Swapnika Reddy Rachapalli and Sarani Saha (2018), “Stigma of sexual violence and women’s decision to work”, World Development, 103: 226-238. Available here.

- Chakraborty, T and N Lohawala (2021), ‘Women, Violence and Work: Threat of Sexual Violence and Women's Decision to Work’, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Discussion Paper No. 14372.

- Kondylis, F, A Legovini, K Vyborny, AM Zwager and L Cardoso De Andrade (2020), ‘Demand for ‘safe spaces’: Avoiding harassment and stigma’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 9269.

- Luca, Dara Lee, Emily Owens and Gunjan Sharma (2019), “The effectiveness and effects of alcohol regulation: evidence from India”, IZA Journal of Development and Migration, 9: 1-26.

- Mukherjee, Chandan, Preet Rustagi and N Krishnaji (2001), “Crimes against women in India: Analysis of official statistics”, Economic and Political Weekly, 36(43): 4070-4080.

- Siddique, Zahra (2021), “Media Reported Violence and Female Labor Supply”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, forthcoming.

- UN-Women and ICRW (2013), ‘Unsafe: An epidemic of sexual violence in Delhi's public spaces: Baseline findings from the Safe Cities Delhi Programme’, UN Women.

06 September, 2021

06 September, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.