Although the rising demand for services has led to its increased contribution to employment in many developing countries and globally, India's growth in services has not translated into a proportionate increase in employment. Rupa Chanda examines two factors which need to be considered if services are to play a bigger role in job creation– improving the quality of jobs along with increasing formalisation of labour, and investing in skills and training to face technological changes.

Globalisation, climate change, technological progress and demographic changes are shaping the future of work. Across countries, creating quality jobs and adapting to emerging labour market requirements has become the need of the hour– particularly as countries strive towards more inclusive and sustainable growth. Against this backdrop, the role of services in providing quality employment has become increasingly important, given the sector’s growing contribution to GDP, foreign direct investment (FDI), trade, and productivity worldwide.

The service sector in India, and globally

Today, services account for 68% of global GDP, and have replaced agriculture as the dominant sector in many developing economies. Increased ‘tradability’ of services – made possible by advancements in information and communication technology – has caused the share of services in global trade to rise from 9% in 1970 to around 20% in 2019 (World Trade Organization (WTO), 2019). The growing role of services in the economy is also mirrored by its growing contribution to global employment. This is due to the rising demand for services that accompanies affluence, changing demographics, and innovation, all of which have pulled more workers into services activities.

In India, the role of services as a driver of employment has assumed greater significance owing to the sector’s dominant share in the economy. As per statistics from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the sector accounted for over 60% of GDP (inclusive of construction services) in 2019; 60% of all cumulative FDI inflows into India for the period between 2000 and 2018 period (at $222.9 billion); and 40% of its total exports (Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP), 2017). Services exports have been dynamic, rising from $6.8 billion in 1995 to $203.3 billion in 2020. In 2020, India’s share in global services exports stood at 4%, compared to less than 2% in case of goods, reflecting its competitiveness in services relative to goods. IT, IT enabled services, and other business services have been the key drivers of India’s services exports.

The questions that arise – and that I address in this piece – is whether services (and in particular, services exports), a dynamic part of India’s growth trajectory for the past two decades, and their integration with world markets can provide the jobs that India’s labour force needs. If so, which segments hold promise, what are the potential implications, and what is needed to realise this potential? Can the dynamism witnessed in India’s services GDP and exports, particularly in selected segments such as IT and business services, translate into a commensurate increase in employment? Finally, what will be the nature of these jobs?

Services employment in India

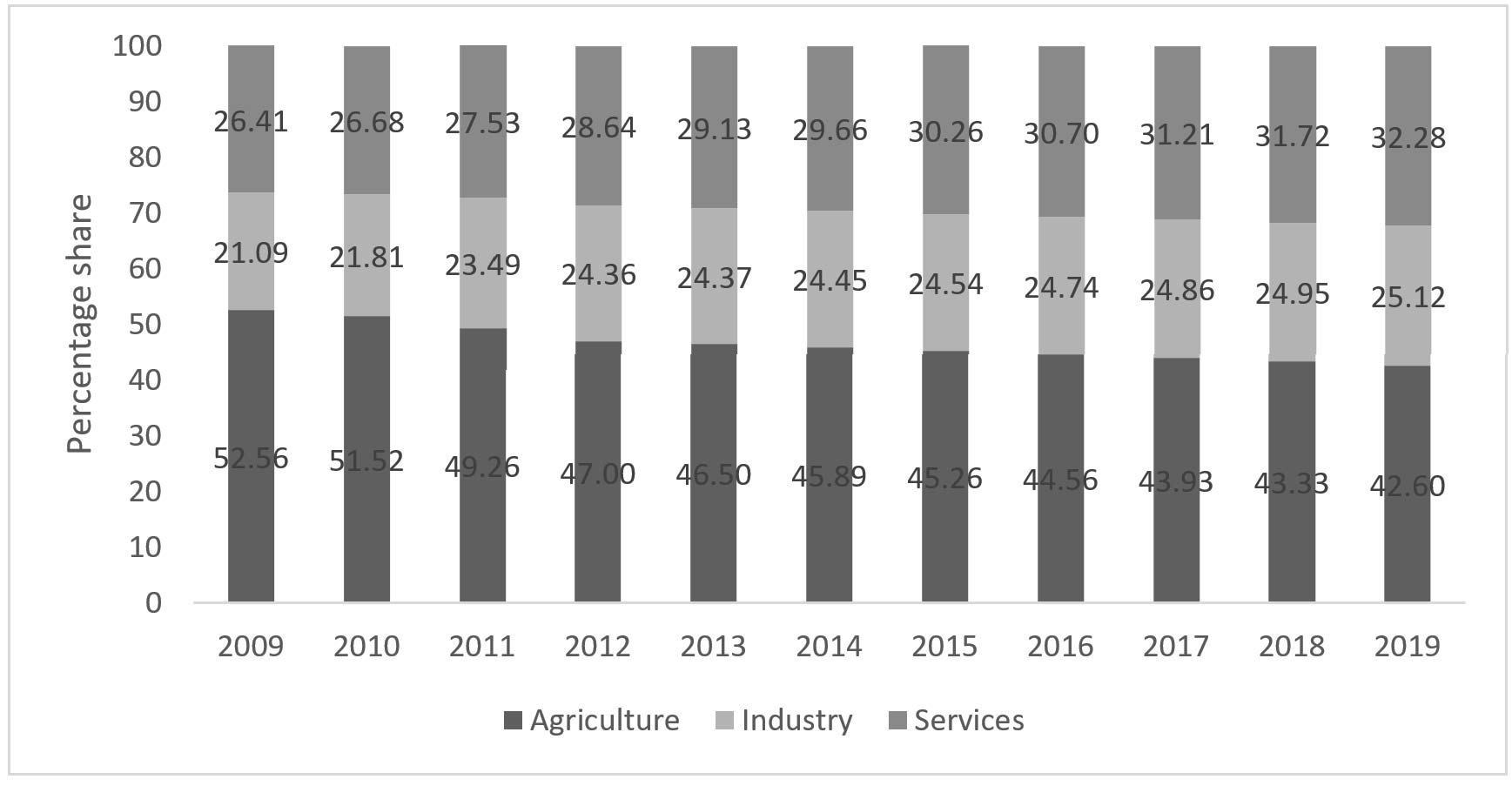

With its share in GDP rising significantly over the past few decades, It is well known that the service sector has played a significant role in India’s structural transformation. However, the outcome on the employment front is mixed. Although the sector’s contribution to employment has risen over time, this increase has been relatively slow. As highlighted in the Economic Survey 2016-17, while services constituted over 50% of GDP, they accounted for less than 30% of total employment. Figure 1 captures trends in the sectoral composition of employment, and highlights the rather slow pace of employment absorption into services over the decade.

Figure 1. Distribution of India’s workforce across sectors from 2009-2019

India has also lagged behind other countries in terms of the contribution of the services sector to employment, as shown in Table 1. The sector’s share in employment rose by 8 percentage points between 2000 and 2019 while the corresponding increase for a country like China (which is recognised for its industrial sector) was nearly 20 percentage points.

Table 1. Contribution of services, as a share of total employment

|

|

2000 |

2010 |

2019 |

|

Brazil |

61.68 |

64.78 |

70.94 |

|

China |

27.49 |

34.60 |

47.25 |

|

India |

24.04 |

26.68 |

32.28 |

|

Malaysia |

49.46 |

59.09 |

62.72 |

|

Philippines |

47.03 |

51.36 |

58.03 |

|

South Africa |

62.82 |

70.75 |

72.41 |

|

UK |

73.30 |

79.57 |

80.83 |

|

USA |

73.94 |

78.94 |

78.74 |

|

World |

39.37 |

44.47 |

50.58 |

Source: World Bank data

The lack of commensurate contribution of services output and trade growth to India’s employment reflects a number of factors: this includes the low employment-intensity and productivity-driven nature of services growth1 in India, failure to absorb surplus labour from agriculture into manufacturing and services, skill mismatches, and difficulties in capturing much of the informal employment that is present in India’s service sector.

Features of service exports and the role of tradable services

The largest single contributing segment is construction services, followed by trade and distribution services, and transport and logistics services. The latter segments, which can be classified as traditional services, together account for around two-thirds of service sector employment. Other segments, which include modern services such as financial, IT, and business services, as well as social and personal services such as health and education, constitute a smaller share of the jobs at present. However, evidence from the Economic Survey (2021-22) suggests that these non-traditional and emerging services have become, and will continue to be, important contributors to employment.

While there has been high growth in organised sector jobs across a wide range of services, it is IT and business process outsourcing (BPO) services – a segment that is largely export-oriented– which has recorded the highest growth rates in job creation. In 2020-21, there were an estimated 4.47 million jobs in IT and BPO services in India; women employees comprise 36% of the total employment in this sector. Further, this segment also generated significant ancillary employment in industries such as transport, real estate, and catering: an estimated 12 million indirect jobs were created in these supporting industries in FY 2020-21, reflecting the IT sector’s huge multiplier effect.

It would thus appear that tradable services such as IT-BPO can be an important source of direct and indirect employment. This is also supported by an OECD study which finds that export of cross-border services supported close to 15% of services jobs in India (Gonzales et al. 2015). But it is important to step back and look beyond these figures to assess future growth prospects of tradable services and if they can really provide the required impetus for job creation in India, given their current composition, competitiveness, and other factors.

A quick review of India’s services export basket and competitiveness indicators suggests that in the near future, this employment potential is likely to be limited. India’s services exports are highly concentrated in two segments – computer, and information and other business services – which together accounted for 70% of India’s total services exports in 2020, as per UNCTAD statistics; this is much greater than that in comparable developing economies. India’s transport and travel services exports in contrast accounted for a much smaller share of total services exports. Thus, India lacks broad-based export competitiveness in services, with only IT-BPO services and other business services showing revealed comparative advantage.

Various infrastructural, quality and regulatory constraints affect India’s competitiveness in most services, and result in a rather skewed export basket comprising mainly of skilled and professional services. For instance, although tourism services offer prospects for good quality, diverse jobs, the segment is plagued by infrastructural issues, and remains untapped. Likewise, although there is huge potential for job creation from medical tourism, it remains unrealised. The related multiplier effects on the economy, and prospects for indirect job creation across skill levels are potentially significant in these other services, but these gains are difficult to realise due to the lack of a diversified services export basket.

Pathway to service sector jobs: formalisation and skills

The bulk of jobs generated in India’s services sector today in construction, distribution, and transport services, are aimed at the domestic market. If indeed tradable services are to play a greater role in meeting India’s employment needs, several issues need to be considered. The first concerns the role that tradable services can play in improving the quality of jobs and harnessing India’s demographic dividend.

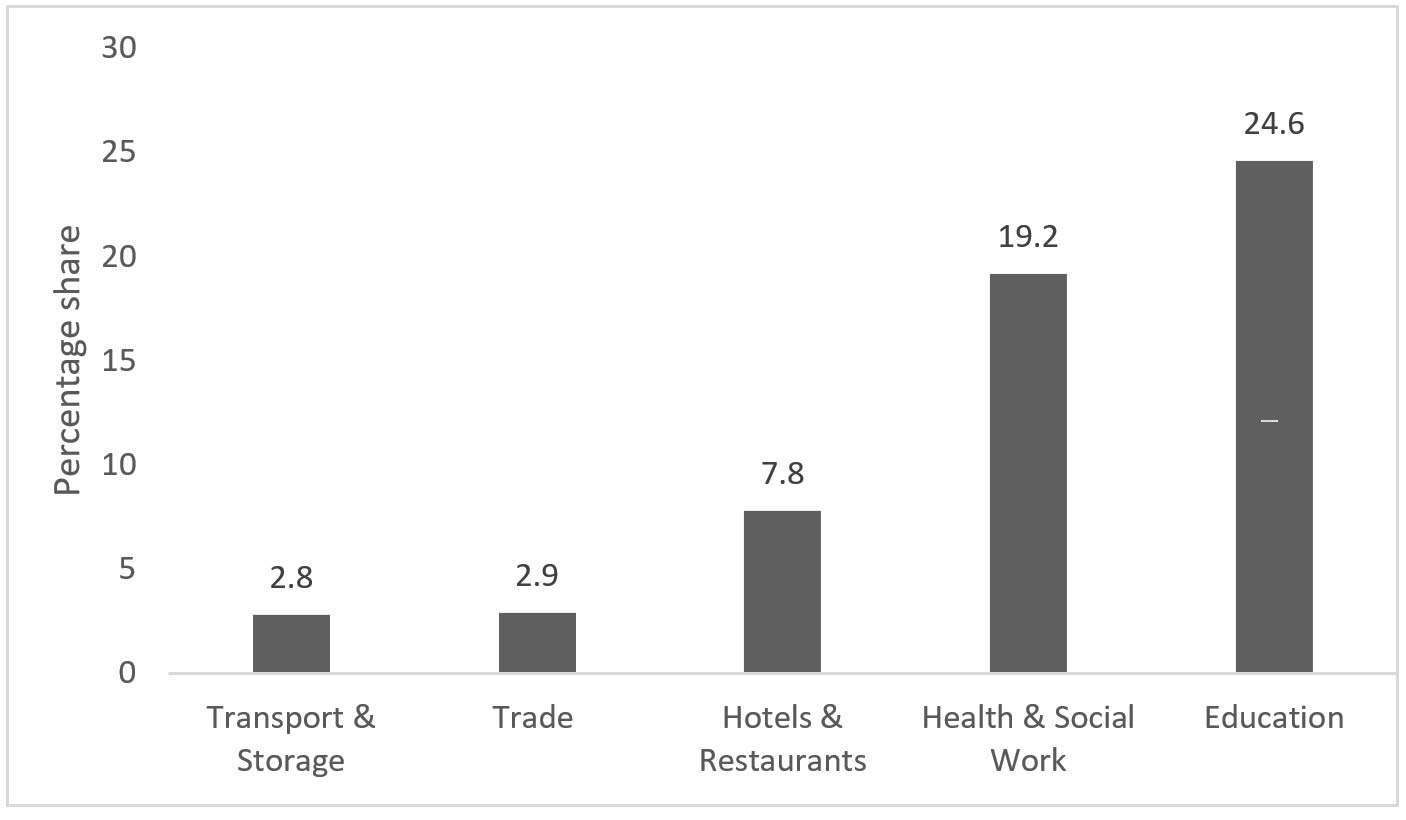

Poor job quality, with high rates of informality and without adequate social protection, is a major challenge for India’s labour market. This is also true of service sector employment, which is largely concentrated in segments which are characterised by low-skilled, low-income, unorganised jobs. Figure 2 highlights the low share of organised sector employment across different services.

Figure 2. Share of organised employment in selected services segments

Against this backdrop, tradable services can play an important role by enhancing the quality of jobs and helping in the formalisation of employment. In addition, their contribution towards formalising ancillary jobs across a range of supporting services can also be significant.

On the gender front too, India’s tradable services can potentially help bridge the gender gap in India’s labour market and address the declining female workforce participation rates which have been a major source of concern in recent years. As per modelled ILO estimates, in 2019, services accounted for 33% and 28% of male and female employment, respectively. Growth in employment in export-oriented services can help bring more gender- balance in the job market given their relatively higher shares of female employment compared to most traditional services.

Thus, from both the formalisation as well as gender perspectives, services trade can be beneficial. It is worth noting, however, that the contribution to job quality and gender parity could be much greater if India’s services exports were more diversified, with a greater role of services such as tourism, health, education that cater to a greater range of skills and can provide jobs more uniformly across the country.

The extent to which services exports can address India’s jobs challenge also depends in large part on how well the jobs that are created are aligned to the available skills and training in the labour market. It is well known that India’s labour force is characterized by a large supply of young but poorly trained workers. According to the FY 2016-17 annual report of the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, only 5% of the workforce has undergone formal skills training. This reflects in employment statistics– in 2019, 53% of Indian businesses were unable to hire candidates due to a lack of futuristic skills such as in Artificial Intelligence (AI), robotics, and cybersecurity, to name some. Although employability has improved, there remains a mismatch between what fast-growing competitive services like IT and business services need, and the available pool of talent and skill sets. This clearly limits the ability of tradable services to create jobs in India unless there is corresponding investment in related skills.

Table 2 highlights the very low shares of formal skill development that are being imparted across different services, and the relatively greater dependence on on-the-job training of workers. This reflects the lack of a labour force that is ready to take advantage of job opportunities in the service sector, with much of the onus falling on businesses to ready their workforce.

Table 2. Sector-wise distribution of share of organisations offering formal skill development training and on-the-job training

|

Sectors |

Skill training |

On-the-job-training |

|

IT/BPOs |

29.8 |

36.1 |

|

Financial services |

22.6 |

38.8 |

|

Education |

21.1 |

22.1 |

|

Health |

20.2 |

24.0 |

|

Manufacturing |

17.4 |

28.3 |

|

Construction |

15.5 |

26.0 |

|

Transport |

13.0 |

20.6 |

|

Trade |

11.2 |

17.4 |

|

Accommodation and restaurants |

7.1 |

13.4 |

|

Total (across these sectors) |

17.9 |

24.3 |

In the future, the demand-supply gap in services, particularly in advanced technologies in sectors such as IT services, is likely to widen due to rapidly changing skilling requirements. While the growth of the digital economy and e-commerce is creating new job opportunities in tradable services, it is also shifting the demand towards highly skilled professionals who possess new age technological tools and knowledge of domains such as AI, cybersecurity and cloud. There is, however, a severe talent crunch for niche digital skills – currently, digitally skilled workers comprise only 12% of the workforce. To keep pace with technological advancements and demand, the number of workers in India requiring digital skills will need to increase nine-fold between 2020 and 2024, and the average worker will need to develop seven new digital skills by 2025.

There is also the added challenge of automation, with jobs across a range of sectors, including many services, becoming increasingly vulnerable to redundancy. It is worth noting that not only are low-skill, low-wage jobs at risk, but so are medium-skilled exportable services such as banking, accounting, and various back-office support activities. The latter can potentially constrain the prospects for lower-end BPO services exports in future, and related job creation.

Thus, technological change and labour market disruptions could limit the prospects for export-driven service sector employment in India. On one hand ‘Industry 4.0’ will create new roles that require additional skilled workers, but on the other, many existing jobs may be destroyed. Thus, the impact of services exports on employment in India will depend on the net effect of these labour market dynamics and how equipped India’s labour force is with the skills of the future.

Concluding thoughts

India’s services exports have the potential to create jobs, but this scope is constrained due to two main reasons: First, the lack of a diversified services export basket. Second, is the shortage of requisite skills and talent. For tradable services to play a greater role in addressing the needs of India’s young labour force, both these constraints will have to be addressed.

Diversification of India’s services exports will require broad-basing the export basket beyond IT-BPO and other business services, as well as securing new markets and geographies, and diversifying the mode of services exports2 beyond cross-border supply (mode 1) and movement of service providers (mode 4) which currently dominate India’s services exports.

To address the skill and talent gap, there is need for more investment in education and training which focusses on emerging technologies and digital literacy. Industry-government partnerships within India, as well as partnerships with other countries through apprenticeship and training programmes, can play an important role in imparting such skills and enhancing employability in services. There is also scope to use comprehensive economic cooperation and partnership agreements, as well as customised bilateral mobility arrangements with other countries, to promote services exports through different modes and generate related employment across a wide range of services.

More generally, for services to contribute to employment in a manner commensurate to their role in output, the sector needs to be part of an integrated strategy, where it is placed alongside manufacturing, and the interdependencies between the two sectors are explicitly recognised. This is needed because services are an increasingly important part of the manufacturing value chain, starting from R&D services to transport, logistics, sales and marketing, which are involved in the production and sale of a product. Hence, services exports are embedded in goods production and exports. A competitive manufacturing sector would enable services exports to grow indirectly, with resulting gains in employment in both sectors. Hence, a coherent industrial strategy which strengthens the linkages between manufacturing and services, and does not approach the two sectors in a siloed manner, would ultimately benefit India’s labour market.

This post is the fifth in a six-part series on 'The good jobs challenge in India'.

Notes:

- That is, growth which is driven not by increased use of labour, capital, or other resources, but by increased efficiency and productivity in these services.

- The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) regime of the WTO classifies services in terms of their delivery modes. As per the GATS, there are four modes of services, including cross-border flow of services, consumption abroad (mode 2), commercial presence (mode 3) and movement of service providers which is not linked to permanent residence or immigration.

Further Reading

- Basole, A, A Jayadev, A Shrivastava and R Abraham (2018), ‘State of Working India 2018’, Centre for Sustainable Employment, Azim Premji University.

- Chanda, R (2020), ‘India’s Services Trade: Opportunities, Challenges and International Engagements’, in P De, A Raychaudhuri and S Gupta (eds.), World Trade and India: Multilateralism, Progress and Policy Response.

- DIPP (2017), ‘Fact Sheet on Foreign Direct Investment, April 2000-March 2017’, Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion.

- Gonzales, F, JB Jensen, Y Kim and HK Nordås (2015), ‘Globalisation of Services and Jobs’, in Policy Priorities for International Trade and Jobs, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- Government of India (2022) ‘Economic Survey 2021-22’, Ministry of Finance, Department of Economic Affairs, Government of India.

16 September, 2022

16 September, 2022

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.