India’s Community Radio Policy, 2006, enables educational institutions and NGOs to establish community radio stations to address local development issues via locally produced content. This article shows that exposure to community radio improves women’s outcomes in terms of education, marriage and fertility. The evidence makes a case for leveraging grassroots media to address gender inequality at scale in developing countries.

In India, as across much of the world, the interaction of early marriage, early motherhood, and low educational attainment disempowers women and limits their life opportunities. Even as countries grow richer, gender inequality is often sustained by social norms, thereby constraining welfare gains from women’s empowerment (Duflo 2012, Jayachandran 2015). Now, the question facing both policymakers and researchers is: how can gender inequality be addressed through policy?

One particularly promising avenue is the use of media as a policy instrument. Previous research suggests that media exposure affects attitudes and behaviour when listeners can relate to stories and characters (DellaVigna and La Ferrara 2015). For example, Jensen and Oster (2009) show that the introduction of television in rural India substantially changed women’s status and autonomy by exposing them to different, more urban, ways of life. But how can policymakers harness the power of the media? And how can they move beyond single-issue information campaigns to target outcomes at scale and over long time periods?

The long road to India’s community radio policy

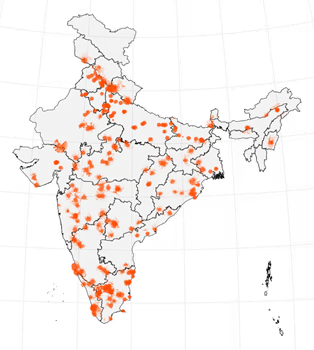

Following a 1996 Supreme Court ruling to free up airwaves to the wider public as well as a decade of lobbying by civil society, activists, and international organisations, India enacted a new community radio policy to foster economic and social development in 2006 (Pavarala 2007). The policy enables educational institutions and NGOs to establish community radio stations to address local development issues via locally produced content. Apart from being barred from broadcasting political news, these radio stations make their own editorial choices (Raghunath 2020). By 2020, more than 250 community radio stations had been launched, with an estimated 331 million people living in areas covered by the stations (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Estimated coverage areas of community radio stations launched by 2020

Note: The figure depicts the estimated coverage areas of community radio stations as of 31 March 2020. To obtain information on these, I build on a list of community radio stations published by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. I geo-located stations by rigorously searching for and identifying their precise location on the Web using information on their name, address, and license holder. In total, I could identify the precise locations of 264 out of 276 operational stations. Using these in combination with information on radio tower height and transmitter power, radio stations’ coverage areas were estimated using the Longley-Rice/Irregular Terrain Model, a standard radio-propagation model used to predict coverage areas by accounting for local topographic features and the technical details of the transmitter. After computing these, I match the coverage areas to high-resolution population data provided by WorldPop. I estimate that a total of 331 million live in the coverage area of at least one community radio station by 2020.

Focus of community radio stations on women’s empowerment and education

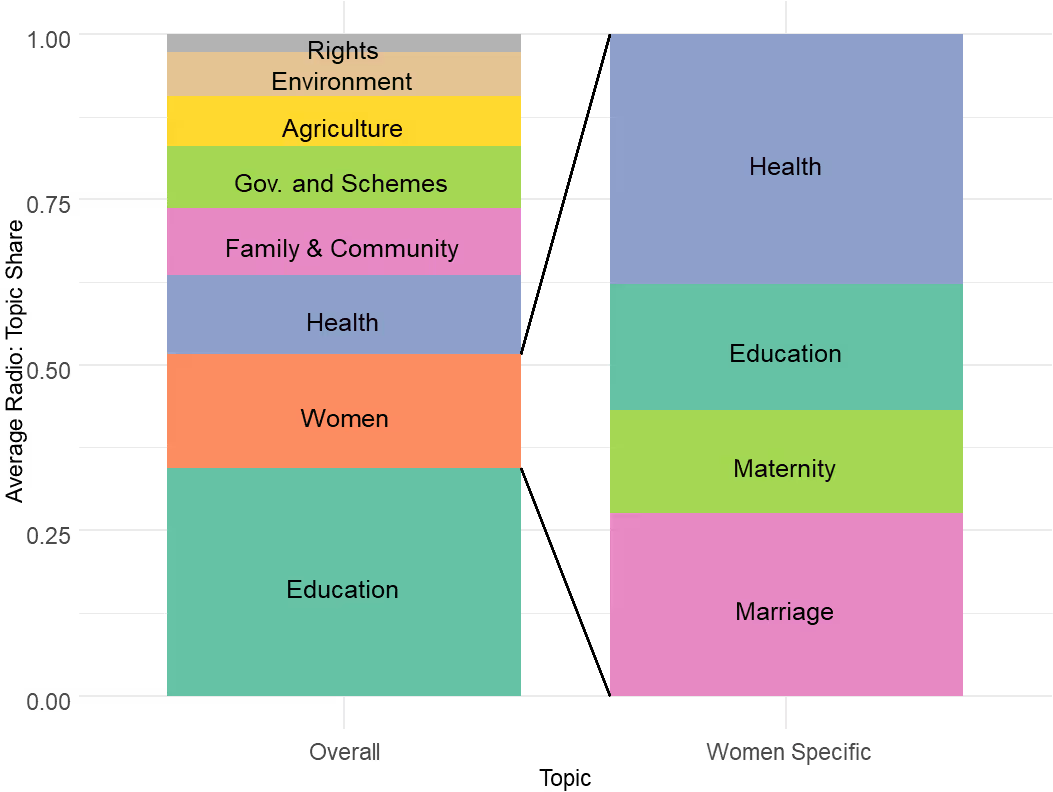

Given community radio stations’ editorial freedom, the first question is what issues they choose to discuss. To find out, I transcribe, translate, and analyse thousands of recorded radio shows uploaded to edaa.in, a website that allows community radio stations to share content with one another. The topic analysis (Figure 2) indicates that around half of the development-related content of the average radio station is related to women’s empowerment or education, though radio stations also cover a lot of other ground. The finding is echoed in a survey of community radio stations by SMART (2023), an NGO, showing that more than 90% of stations broadcast content related to gender.

Figure 2. Average radio station’s share of content across topics based on topic model

Note: The figure visualises the distribution of topics of the average radio station. For this, translated transcripts of radio shows are assigned topic shares using an LDA model. Specifically, LDA models treat the transcripts as a mix of latent topics, where topics are probability distributions over terms. Based on these assumptions and the terms used in the respective transcripts, the LDA then defines topics and shows what share of each transcript is drawn from which topic (see Hansen et al. (2018) for more details). After naming the topics drawing on their most predictive terms, I first compute each radio station’s average topic share and, based on this, the average radio station’s content. Before doing so, I exclude entertainment (24% of average radio station’s uploaded content) and other undefined topics (17%) from the visualisation to provide an idea of development-related messages.

Yet, while the analysis shows that radio stations discuss girls’ education, they may not argue in favour of it. I use ChatGPT to find out: For this, I first send all transcripts to ChatGPT to identify those discussing four key issues related to gender inequality: child marriage, education, family planning, and domestic violence. After identifying transcripts discussing, say, child marriage, I again send these to ChatGPT and ask whether the radio show makes a statement in favour of, neutral toward, or against child marriage. Overall, the results suggest that 96% of shows with content on these four issues discuss them in a way that economists would typically define as in line with women’s empowerment. Specifically, they endorse girls’ education and family planning and condemn child marriage and domestic violence. A few shows are neutral, while close to none argue in the other direction.

Evaluating the impact of community radio on women’s empowerment

To causally measure the effects of India’s community radio policy on women’s empowerment, I first collect data on the locations of the more than 250 community radio stations that had been launched by 2020 (Rusche 2025). Based on locations and technical details, the coverage areas were estimated (see note of Figure 1 for details on data collection). For data on individuals’ outcomes, I rely on the 2015-16 National Family and Health Survey, which was conducted around 10 years after the first radio stations were launched (International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF, 2017). I focus on individuals living in the proximity of the radio tower that launched before 2016, that is, those with a non-zero chance to receive a radio signal. In my main analyses, this includes people living within a 50-kilometre radius of a radio tower.1

When assessing the effects of community radio, unfortunately – at least from a researcher’s perspective – radio towers and, hence, their coverage areas are not placed at random but tend to be built in more developed areas. Thus, even after taking out variation related to regional and individual-level characteristics, effects of radio cannot be cleanly measured.

Nevertheless, in order to find out about the effects of community radio, I rely on an identification strategy that was first introduced by Olken (2009). It draws on the idea that whether someone receives a radio signal is driven by three components, two of which are likely also related to the status of women. The aim is to only rely on variation in the third component to find out about the effects of community radio. The first two components are the distance to the radio tower and the topography of the surroundings of individuals. Both may affect whether someone receives the radio signal. Simultaneously, both are likely predictive of variables such as urbanisation or remoteness, which may be related to the status of women. To ensure that these factors do not drive the results, I take out variation related to them by controlling for a location’s altitude and ruggedness, as well as for individuals’ distance from the radio tower.

Following the above steps, differences in radio reception that remain stem from the line of sight between the radio tower and the receiver. For example, a hill that is neither related to the individual’s surrounding terrain nor to its distance to the tower may block the signal from reaching a certain location. I use this remaining variation to find out about the effects of radio. I test the validity of this approach in several ways. For example, if the above idea holds, the variation in radio reception should not be predictive of variables that are unlikely to change through radio, but may change be related to women’s outcomes, such as population density, urbanity, caste, or religion. I do not find it to predict these and various other variables. This strengthens the argument that, after removing variation related to the two components above, I am statistically comparing very similar locations that differ in their radio reception.

Women’s role changes with exposure to community radio

I find that households exposed to community radio are 25% more likely to have heard a family planning message and 42% more likely to have heard a message on HIV/AIDS on the radio relative to the sample average. Hence, community radio stations increase exposure to the messages they typically produce. I also find a positive, but somewhat weaker, effect on overall radio consumption.

Women exposed to community radio gain an additional 0.3 years of education on average and are less likely to drop out of school. Overall, they are 34 percentage points more likely to obtain a primary, secondary, and higher education degree. As evidenced by changes in reasons for school dropout, the increase in educational attainment is not driven by improvements in school infrastructure or accessibility but stems from increased aspirations among parents and girls themselves. Further, parents are less likely to cite marriage as a reason for dropout. This is also reflected in a 1.4 percentage point (or 22%) decrease in child marriage among girls. Moreover, women exposed to community radio are less likely to get married up to the age of around 25. The effects for men are similar but lagged by around five years, which roughly mirrors the age gap between men and women in my sample.

I also find drops in fertility. Women in exposed areas have 8-12% fewer children between the ages of 19 and 35. These changes are not only suggestive of delayed childbearing but may also reflect a reduction in lifetime fertility. Such a decrease can have profound implications for women’s health and economic opportunities.

Finally, the impact of community radio stations extends beyond education, fertility, and marriage. While data on the following outcomes are only available for a third of survey locations, I find that young women in areas with community radio are 11 percentage points more likely to participate in household decisions and to have greater autonomy over their mobility. Notably, men also exhibit signs of shifting attitudes –there is an increase in the share of household decisions in which they believe women should participate. This indicates that community radio is not only empowering women but also facilitating changes in gender norms among men.

Conclusion and policy implications

My research provides evidence for strong effects of India’s community radio policy on women’s empowerment. This suggests that grassroots media policies like those in India can serve as an effective policy tool for developing countries. Given limited government resources, the policy provides a way to draw on civil society’s resources and knowledge to affect development outcomes. These institutions’ knowledge of local issues is likely to be particularly valuable in culturally and linguistically diverse countries. Moreover, community media feature people close to the lives of the listeners. As such, these may be better able to activate peer effects. Not least, community radio can potentially address populations with little trust in the government and, hence, government media campaigns.

For Indian policymakers, the takeaway from these results is that community radio has been successful in empowering women. To further expand the scheme, the government can promote it more strongly to eligible organisations. From discussions with stakeholders, I found that the complexity of the licensing process constitutes a bottleneck in the admission of additional licenses. The government may also offer support in the process or simplify it further to increase the number of (successful) applicants. Raising available funding to finance startup costs, such as buying radio equipment, may further reduce barriers to entering the market, as would reducing licensing fees. Besides, policymakers may consider allowing at least some stations to increase their transmitter power or tower height. In some terrains, radio stations may otherwise not be able to reach a critical mass of listeners to be financially sustainable.

Note:

- When combining the two data sources, one issue arises: the locations of survey respondents are not precisely observed. To preserve the privacy of survey respondents, precise GPS coordinates of survey locations are randomly displaced by up to 5 kilometres (in rural areas, 1% are displaced by up to 10 kilometres). This introduces measurement error. To solve this, I develop a novel method that draws on knowledge of the displacement algorithm in combination with external data to compute the probability that a given individual was surveyed within the coverage area, given the displaced location I observe. I show that this resolves the issue that results from the displacement.

Further Reading

- DellaVigna, S and E La Ferrara (2015), ‘Economic and Social Impacts of the Media’, in SP Anderson, J Waldfogel and D Strömberg (eds.), Handbook of Media Economics, 1A .

- Duflo, Esther (2012), “Women Empowerment and Economic Development”, Journal of Economic Literature, 50(4): 1051-1079.

- Hansen, Stephen, Michael McMahon and Andrea Prat (2018), “Transparency and Deliberation Within the FOMC: A Computational Linguistics Approach”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(2): 801-870.

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF (2017), ‘National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India’.

- Jayachandran, Seema (2015), “The Roots of Gender Inequality in Developing Countries”, Annual Review of Economics, 7(1): 63-88.

- Jensen, Robert and Emily Oster (2009), “The Power of TV: Cable Television and Women’s Status in India”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3): 1057-1094.

- Pavarala, V and KK Malik (2007), Other Voices: The Struggle for Community Radio in India, Sage Publications India, New Delhi.

- Olken, Benjamin A (2009), “Do Television and Radio Destroy Social Capital? Evidence from Indonesian Villages”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(4): 1-33.

- Raghunath, P (2020), ‘A Glocal Public Sphere: Opening up of Radio to Communities in South Asia’, in Community Radio Policies in South Asia: A Deliberative Policy Ecology Approach.

- Rusche, F (202), ‘Broadcasting Change: India’s Community Radio Policy and Women’s Empowerment’, Discussion Papers of the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, No. 2025/5.

- SMART (2023), ‘Gender Analyses in Community Radio Stations, 2023’, Technical Report, SMART NGO, New Delhi.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

%201.svg)

.svg)

.svg)